.

Strategies to Increase Effective Political Engagement

An American Muslim Case Study

OCTOBER 6, 2020 | BY AZKA MAHMOOD

SUMMARY

The state of Virginia has emerged as a forerunner in increasing effective political engagement among American Muslims. In fact, Virginia accounted for 8 of the 26 American Muslim electoral wins nationwide in 2019. This case study explores the journey of a group of American Muslims from northern Virginia that took measures to create and nurture an ecosystem to improve their community’s political engagement. The group’s strategic aim was to increase American Muslim participation and representation at local, city, county, state, and national levels through volunteer service, appointment, and election.

.

Executive Summary

Background

Recent studies show a steady increase in American Muslims’ participation in the electoral process. Historic numbers of American Muslims ran for office for various levels of government in 2018. According to ISPU’s 2020 American Muslim Poll, Muslim voter registration increased from 60% in 2016 to 78% in 2020. In 2020, the 116th U.S. Congress includes three American Muslim representatives—the highest number of Muslims in Congress in history.

Still, Muslims are underrepresented within the higher levels of government. American Muslims make up an estimated 1.1% of the total U.S. population, yet their representation in Congress is less than 0.6%. Despite efforts by legacy and emerging American Muslim organizations, American Muslim voter turnout, involvement in public service, and government representation belie their true numbers and fall short of their professional and economic potential.

In the absence of true representation and involvement, American Muslims are often subjects rather than participants in debates about American Muslims and their concerns, and they rely on others to define them and pursue their interests. Allyship does not automatically translate into policy alignment, and, thus, lack of American Muslim representation in government means their concerns are not addressed. Amid this quandary, the state of Virginia has emerged as a forerunner in increasing effective political engagement among American Muslims. There are about 170,000 American Muslims in Virginia, making up about 2% of the total state population. Virginian Muslims are represented in virtually every profession and worship in about 100 mosques in various cities and towns. Not only have Virginian Muslims shown remarkable advancement in their numbers as volunteers in public service in the last few years, but Virginia also accounted for 8 of the 26 American Muslim electoral wins nationwide in 2019.

TABLE OF CONTENTS

Executive Summary

Introduction

Inception + Strategic Vision of the NoVa Group

Foundation + Levers of Effective Political Engagement

Results, Sustainability, + Future

Challenges + Room for Improvement

Lessons Learned

Timeline of Recent Noteworthy American Muslim Electoral Achievements

Sources

SUMMARY

The state of Virginia has emerged as a forerunner in increasing effective political engagement among American Muslims. In fact, Virginia accounted for 8 of the 26 American Muslim electoral wins nationwide in 2019. This case study explores the journey of a group of American Muslims from northern Virginia that took measures to create and nurture an ecosystem to improve their community’s political engagement. The group’s strategic aim was to increase American Muslim participation and representation at local, city, county, state, and national levels through volunteer service, appointment, and election.

.

Executive Summary

Background

Recent studies show a steady increase in American Muslims’ participation in the electoral process. Historic numbers of American Muslims ran for office for various levels of government in 2018. According to ISPU’s 2020 American Muslim Poll, Muslim voter registration increased from 60% in 2016 to 78% in 2020. In 2020, the 116th U.S. Congress includes three American Muslim representatives—the highest number of Muslims in Congress in history.

Still, Muslims are underrepresented within the higher levels of government. American Muslims make up an estimated 1.1% of the total U.S. population, yet their representation in Congress is less than 0.6%. Despite efforts by legacy and emerging American Muslim organizations, American Muslim voter turnout, involvement in public service, and government representation belie their true numbers and fall short of their professional and economic potential.

In the absence of true representation and involvement, American Muslims are often subjects rather than participants in debates about American Muslims and their concerns, and they rely on others to define them and pursue their interests. Allyship does not automatically translate into policy alignment, and, thus, lack of American Muslim representation in government means their concerns are not addressed. Amid this quandary, the state of Virginia has emerged as a forerunner in increasing effective political engagement among American Muslims. There are about 170,000 American Muslims in Virginia, making up about 2% of the total state population. Virginian Muslims are represented in virtually every profession and worship in about 100 mosques in various cities and towns. Not only have Virginian Muslims shown remarkable advancement in their numbers as volunteers in public service in the last few years, but Virginia also accounted for 8 of the 26 American Muslim electoral wins nationwide in 2019.

Defining Effective Political Engagement

This case study explores the journey of a group of American Muslims from northern Virginia (called the NoVa group in this report) who took measures to create and nurture an ecosystem to improve their community’s political engagement. The NoVa group had a strategic aim to increase American Muslim participation and representation at local, city, county, state, and national levels through volunteer service, appointment, and election. In this report, we define political engagement as 1) active involvement with governing bodies as part of a decision-making and public service group as a volunteer, 2) designation as an official volunteer or staff for candidates’ campaigns, 3) official appointment in a governmental position, and 4) organizing fundraisers and donations for political candidates in a systematic way.

Virginia Muslims’ Political Engagement Pre-2009

In Virginia, American Muslims participated in President Obama’s first election campaign in an unprecedented way. However, the fervor and momentum died down after President Obama was elected without any change in the long-term political engagement of the American Muslim community. Soon after the conclusion of the 2008 election cycle, a group of American Muslim leaders that later formed the NoVa group came to the following conclusions:

- American Muslims had focused too much on national elections, despite constituting a small part of the electorate and holding little sway nationwide.

- Most American Muslim community efforts had focused on voting in elections as the only tool to participate in in politics.

- American Muslims had too often directed fundraising efforts to campaigns where their financial contributions had low impact.

- American Muslims had too often backed local candidates with poor odds of winning, resulting in loss of time and money.

The group noted that the outcome of participation in elections in this manner resulted in few tangible gains in terms of actual engagement and representation of Muslims within government. These well-intended efforts were deemed to ultimately have little long-term impact on policies of importance to the American Muslim community. Such participation did not have any bearing on actual relationships and appointments, was riddled with the pursuit of individual glory among American Muslims seeking relationships with political candidates, and highlighted the lack of a long-term strategy for sustained political engagement.

Vision and Core Principles

The NoVa group set a goal to increase American Muslim participation in statewide government. They took steps to create wide-ranging systemic change to encourage voluntary public service, develop and nurture high-quality American Muslim leadership, and create a multifaceted ecosystem to facilitate their ascent into the highest levels of American politics. The group aimed to empower American Muslims to move from reactive political engagement to proactive engagement. The NoVa group believed that service-based grassroots and local level involvement in government would interweave American Muslims in the fabric of American politics, which would ultimately bring forth quality candidates and further the causes important to them as U.S. citizens. As a group of businessmen, the NoVa group focused on the core principles of scalability, collaboration over competition, and the creation of a talent pipeline.

Foundation and Levers of Effective Local Political Engagement

To achieve their goal, the NoVa group first created a foundation by starting a business association to study candidates and build relationships as taxpayers, job creators, and minority business owners. They established a sustainable stream of collective capital through a group of likeminded donors willing to invest in collective rather than individual gain. Next, they identified and utilized three levers of effective local political engagement:

- Votes and voter relationships with candidates vetted through the business association and connected to the American Muslim community through authentic mutual relationships

- Strategic financial investment and deployment of collective capital across several viable contests and candidates

- Suggestions of high-quality and reliable American Muslim volunteers for appointments within candidate campaigns

Results

Over time, the NoVa group cultivated meaningful and long-term relationships with candidates across political, racial, ethnic, and religious lines. Several American Muslim volunteers and staffers were able to ascend political ranks and pursue careers in public service. American Muslim voices were included at the policy level with increasing frequency. In 2019, eight American Muslims won seats including Abrar Omeish, the youngest member ever elected to the Fairfax County School Board, and Ghazala Hashmi, the first American Muslim woman to be elected to the state senate in Virginia.

Challenges

The NoVa group encountered entrenched attitudes disfavoring public service careers in the American Muslim community. The community’s bias against political careers coupled with the professional expectations of the older generation of American Muslims limited the NoVa group’s ability to find and mentor young adult American Muslim professionals to join political campaigns. Deeply ingrained voter apathy, stemming from cynicism and a perception of futility with participating in the electoral process, hindered the NoVa group’s efforts to animate community members to study and support candidates and to take part in midterm and down-ballot races in particular. Moreover, an individual vs. collective glory mindset challenged the group’s efforts to create a collective pool of impactful financial donations made on behalf of the community instead of smaller, less powerful individual donations that community members sought to make for the sake of personal connection.

Room for Improvement

The NoVa group consists of a group of South Asian and Arab men and does not reflect the diversity of Muslims in America. It should be noted that initial group membership coalesced around financial capacity, formed with a focus on bringing together donor members. Still, the initial catalyst group lacked the voices of women and other ethnicities. Limited somewhat by the demographic makeup of the northern Virginia American Muslim community, core members have supported ethnic and religious minority candidates, included women and other minorities in networks, and mentored youths from diverse backgrounds to be more inclusive. Additionally, though the structure and broad strategy of the group are clear, the group lacks a concrete and comprehensive strategy that may be widely understood by community members and replicated by other American Muslim communities. For instance, details on policy matters and outreach methods appear to be unclear.

.

Introduction

In recent years, studies have shown a steady increase in American Muslims’ participation in the electoral process. According to ISPU’s 2020 American Muslim Poll, Muslim voter registration rose from 60% in 2016 to 78% in 2020. Emgage USA found that in four key swing states, American Muslim voter turnout increased significantly in the 2018 midterm elections as compared with the 2014 midterm elections. These increasing numbers are a testament to the unrelenting efforts of dozens of American Muslim organizations dedicated to American Muslim electoral and political engagement.

Yet, across the country, American Muslim voters’ growing intention to vote and registration status remain inconsistent with their actual turnout as voters. Similarly, there has been an increase in the number of American Muslims launching bids for elected office in recent years. In 2018, historic numbers of American Muslims ran for office at various levels of government, and as of 2020, the 116th U.S. Congress includes three American Muslim representatives—the highest number of Muslims in Congress in history. Still, actual representation in elected numbers falls short of American Muslims’ numbers in population. Muslims make up an estimated 1% of the total U.S. population but only 0.6% of Congress, and thus remain underrepresented at high levels of government. Importantly, the dearth of American Muslims at all levels of government falls short of the economic and professional strengths they contribute to society. American Muslim voices and concerns are not adequately addressed or reflected in government, necessitating a push for political representation and participation.

The disparities in participation and representation highlight a persistent, albeit narrowing gap in the way American Muslims engage with the political process. Viewed holistically, the goal of increased political engagement is not only to increase the number of American Muslims in elected office, but to have American Muslim voices heard and to influence government policy in all levels of government. Through this case study focusing on the Commonwealth of Virginia, we seek to gain an understanding of community efforts that may lead to improvement in effective government engagement.

Context for the Commonwealth of Virginia

This document studies political engagement efforts by a group of American Muslims in the Northern Virginia area, referred to herein as the NoVa group. In particular, our case study follows the steps that the NoVa group took to create a platform and an ecosystem that improves their community’s political engagement. The NoVa group had a strategic aim to increase American Muslim participation at local, city, county, state, and national levels through voluntary public service, which they hoped would lead to an increase of Muslims in government via appointment and election. We selected Virginia as a case study because of the remarkable progress made by the Virginian Muslim community in the years following the Obama election. Their advancement is reflected both in significantly increased participation in public service, as well as a marked jump in representation in government, including the historic wins of Ghazala Hashmi and Abrar Omeish. Remarkably, in the 2018 midterm elections, eight American Muslims won seats in the Commonwealth of Virginia.

Virginia is home to approximately 170,000 Muslims, about 2% of the total state population. There are over 100 mosques across the state, and Virginian Muslims are represented in virtually every profession.

Defining Effective Political Engagement

For the purposes of this case study, effective political engagement means participation in the processes of governance. Specifically, we examine political engagement that translates into increased civic engagement—participation and representation at various levels of government. As such, the engagement studied herein goes beyond individual participation such as voting, writing letters, signing petitions, and attending political meetings. We define political engagement as

- active voluntary involvement with civic bodies as part of a public service and decision-making group,

- designation as an official volunteer or staff for political candidates’ campaigns,

- official appointment in a government body, and

- organizing fundraisers and donations for political candidates in a systematic way.

To collect data for this report, we conducted five in-depth participant interviews. Participants were contacted using snowball sampling.

Virginia Muslims’ Political Engagement Pre-2009: “What Are We Doing Wrong?”

The years following the election of President Obama to his first term in office served as a watershed moment for those who would later found the NoVa group. In Virginia, American Muslims’ political engagement had surged to unprecedented levels during President Obama’s first presidential election campaign. The promise of change had buoyed the Muslim community and galvanized it into action. The Virginia Muslim community mobilized for the Obama campaign to fundraise, canvass, and host large phone banking events. However, as the euphoria died down after the presidential inauguration in January 2009, the NoVa group critically analyzed the participation pattern of their own community and American Muslims at large. They found four themes in American Muslims’ historic engagement in democratic processes that, despite taking considerable time, effort, and financial resources, yielded little result. They concluded the following:

- American Muslims focus solely on national elections. Yet, nationwide, Muslims constitute a small part of the electorate and hold little sway, which renders their influence negligible.

- Most American Muslims regard voting in elections as the only effective way to participate in politics.

- American Muslims direct fundraising efforts to campaigns where their financial contributions have low impact.

- When supporting candidates in local races, American Muslims often back candidates with poor odds of winning, resulting in loss of time and money.

Lessons from 2008 to 2009

The NoVa group’s introspection was a direct consequence of the perceived lackluster outcome of the presidential election of 2008 for American Muslims as a community and a quick return to the old pattern of low civic and political engagement. The lessons from 2008 to 2009 as identified by interview respondents are described below.

1. Few Tangible Gains

First, in the immediate aftermath of the 2008 election, there were no tangible gains in representation at the local, state, or national level in terms of political appointments in the Obama administration despite considerable mobilization and significant donations from American Muslims. Despite their efforts to elect President Obama, American Muslims did not gain access to a seat at the table.

2. No Long-Term Strategy for Sustained Local Engagement

Second, the groups and communities that had mobilized for President Obama did not have long-term plans to harness their political momentum for continued engagement. At the risk of falling back into dormancy, the community would lose any gains made as a viable voting bloc and an aware, empowered constituency. The community had poured time and resources into a national election without a plan to participate in local political affairs. This lack of sustainability particularly concerned the NoVa group, since they noted the longstanding disengagement from meaningful local civic engagement among the vast majority of American Muslims to be a major hindrance to their ascent into politics.

3. Me, Not We

Lastly, when American Muslims did participate in political campaigns and supported candidates, they cultivated superficial, transactional, and individual relationships that were not meaningful beyond photo ops. Similarly, if an American Muslim candidate was elected, it represented individual success and did not guarantee a holistic representation of American Muslims. Based on these observations, the self-selected NoVa group set out to chart a strategic plan.

.

Inception and Strategic Vision of the NoVa Group

In 2010 in Northern Virginia, a small informal group of like-minded South Asian and Arab men who ranged from 40 to 60 years old, came together to envision a political future for American Muslims in their state. Part of the same Virginia Muslim community, the men hailed from diverse backgrounds in business, technology, health, and academics. They held in common professional success and stability, as well as several decades of service to the American Muslim community in their personal capacities. The group shared frustration with the lack of meaningful progress of American Muslims in the political sphere despite decades of effort by themselves, other individual American Muslims, faith and community leaders, and legacy organizations. In their view, the community’s efforts were not yielding the desired results, and the small achievements that were made were not being scaled or replicated. As such, each individual success story continued to have a high cost. Further, they noted that American Muslim organizations operated as competitive rather than cooperative entities and that the organizations vied for limited funds and support from the community. Underpinning these concerns was the global understanding that American Muslims’ lack of civic engagement at the community level and the resultant disconnect from local governance was the main obstacle to the achievement of effective political engagement and, ultimately, political representation.

Vision

The NoVa group rooted their vision in the Theory of Social Change. Per the Theory of Social Change, individual efforts to create change or solve a social problem have minimal impact. A step further, changing the way an institution operates to address a social problem improves the chances of impact several-fold. However, true social change occurs when there is systemic change at the top policy levels that works through the individual components of the system. The NoVa group aimed to progress from siloed individual political achievement efforts and reimagine the existing civic engagement approach of American Muslim organizations where success had not proven to be scalable. The group’s goal was to create wide-ranging systemic change; develop, nurture, and animate high-quality American Muslim leadership; and create a multifaceted ecosystem to facilitate their ascent into the highest levels of American politics.

As people of faith, the NoVa leaders wished to awaken the American Muslim community to the opportunity to contribute to the betterment of society through public service and to move beyond traditional philanthropic avenues. They sought to create a platform that could direct American Muslim efforts to decision-making spaces where the impact of their time and effort would be multiplied. The envisioned platform would serve as a clearinghouse to connect talent with opportunities and ideas with resources. Such a system would empower American Muslims to move from reactive political engagement that is reliant on the emergence of a worthwhile cause or political candidate, to proactive engagement by positioning them to catalyze beneficial initiatives that bring forth quality candidates. To the NoVa group, local civic engagement where the benefits of participation and positive influence are amplified is the true essence of the Islamic principle of service.

The bulk of the planning of the NoVa group was directed toward bringing about an ideological change within the Virginia American Muslim community, but the initiative still needed a tangible goal to measure their progress. According to one NoVa group interviewee in the following excerpt, the NoVa group privately set a target to reflect the payoff for their efforts—to have an American Muslim in statewide office by the year 2017:

“We set out with a clear objective. When we started, we literally said, ‘What is our castle in the cloud? What is our vision for the American Muslim community? How do we say we have achieved success? How do we say we have arrived at our objective?’ So, our goal was this: By 2017 we would have an American Muslim in a statewide office.”

Respondent 2, phone interview, September 2019

For the NoVa group leaders, American Muslim elected officials would be the top of a political engagement pyramid, with much greater numbers of volunteers in civic organizations at the base, and appointments based on talent and experience in the middle tier. If an American Muslim could ascend to statewide office, it would demonstrate American Muslim participation in bureaucracy, roles of civic importance, and civil service, in addition to an involvement in government processes at local levels, which was the true goal of the NoVa group’s efforts. Cognizant of the fact that elected numbers are not an accurate proxy for actual political and social influence nor American Muslim participation’s true benefit to society, achievement of this goal would nonetheless prove the efficacy of the concerted effort of the NoVa group in one way.

Core Principles

Some of the visionaries that were NoVa group members possessed extensive knowledge and experience of running multiple successful businesses. As such, the group utilized venture capitalist strategies to solve the problem of lack of participation and representation. These were 1) scalability, 2) collaboration over competition, and 3) talent pipeline.

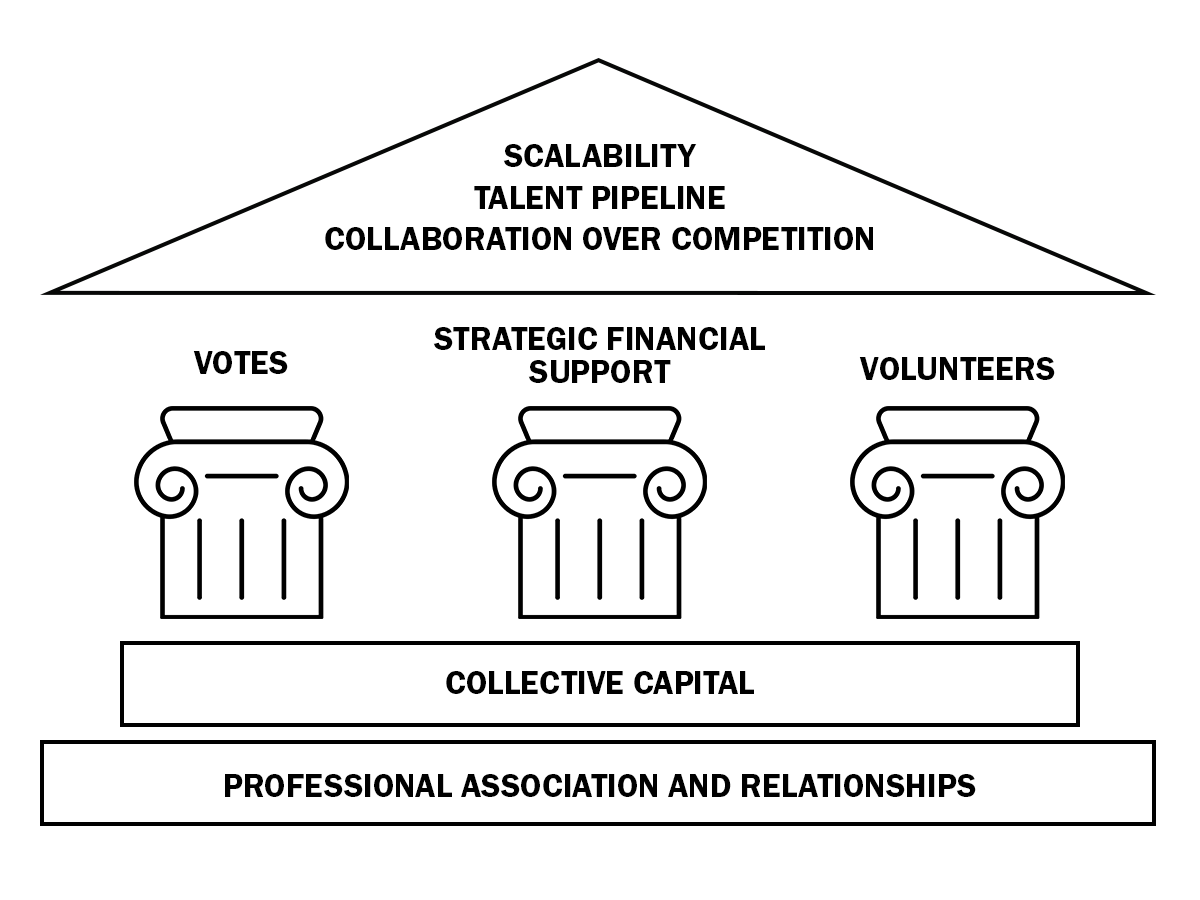

FIGURE 1: The foundation and levers of effective political engagement

1. Scalability

In business, scalability refers to multiplication of revenue with minimal incremental cost. A scalable business thus sets the stage to enable and support unhampered growth. In the American Muslim political engagement context, the NoVa group envisioned an environment where the barriers to entry and cost of each successive American Muslim individual to enter into and advance within the political system would be progressively lower. In an ideal scenario, for American Muslims, the cost of replicating individual success in the political arena should become minimal. The NoVa group sought to create an environment where American Muslims regularly take part in local politics and decision-making, develop relationships and trust with the greater community, and have a track record of quality leadership and service. Such an environment would normalize American Muslim presence in civic matters and enable new American Muslim leaders to ease into political spaces as part of a familiar and productive segment of society without having to recreate relationships for each individual foray into civic life.

2. Collaboration over Competition

In a business setting, a scarcity mindset distracts from higher aims and creates competition for finite resources at the expense of true prosperity. Businesses have greater chances of growth through cooperation with similar-sized entities. The NoVa group, as individuals with multiple positive business experiences grounded in synergy, aimed to create a similarly collaborative model for American Muslim individuals and organizations. The group set out to operate with an abundance approach, the belief that there is room for all Muslim individuals and organizations to succeed and cooperate for ultimate collective benefit. As community leaders, the NoVa group sought to move away from personal-, accolade-, and recognition-based efforts and toward collective goal-orientedness where community efforts would be directed toward initiatives with the greatest payoff rather than individual gain. For American Muslim organizations, the NoVa group imagined an alignment toward the ultimate goal for most—to nurture future American Muslims as forces for good and empower them to create systemic change—and to work together to achieve it.

3. Talent Pipeline

The NoVa group regarded American Muslim representation at statewide and national levels as a pyramid and a progression that builds step by step from local government. As such, the group set out to create a system to encourage American Muslims to serve at lower levels of government with the ability to advance higher. For the NoVa group, the lack of polished and experienced American Muslim candidates lay at the root of the absence of American Muslim government appointments, for instance in the Obama administration, despite the investment by the American Muslim community in the Obama campaign. The following excerpt shows how one interview respondent explained this phenomenon:

“[We are] lacking the basic steps that would lead to national appointments. For someone to be appointed at the national level, they had to have been appointed at the state level. And to be appointed at the state level, they probably needed to have been appointed at the local level or their county… If you have ten people at the local level, then you get five people above, and then maybe one person at state level.”

Respondent 3, phone interview, October 2019

To facilitate the talent pipeline, the NoVa group would identify and encourage qualified American Muslims to take on servant leadership and guide them toward well-suited service opportunities in their vicinity. In this way, individuals would get a chance to contribute their talent to locally beneficial projects, gain a deeper understanding of government bureaucracy and processes, and hone their skills. For American Muslims who may wish to remain involved, the NoVa group effort would serve as the first step in the right direction. In essence, the NoVa group would only feed the initial input, and the pipeline would rely on the self-motivation and capabilities of the individual entrants to move up the political engagement pyramid. The pipeline would organically produce high-quality, trusted, and experienced American Muslim leaders and would create a pool of strong candidates for appointments and elections.

.

Foundation and Levers of Effective Political Engagement

The NoVa group identified three levers of effective political engagement: 1) votes, 2) strategic financial support, and 3) volunteers.

Foundation

In order to engage these levers most effectively and to avoid pitfalls of the past, a two-layered foundation of relationship building and investment capital was built. Through this two-pronged approach, the NoVa group identified partnerships, nurtured relationships, and channeled resources into political campaigns when needed. The two aims of the foundation were achieved through the creation of a professional association and development of a stream of donations.

1. Relationships

The overarching goal of the NoVa group was to increase American Muslim’s benefit to society through civic and political engagement, ideally with increased political representation. However, they realized the dearth of qualified, viable American Muslim political candidates in the short term and the need for American Muslims’ ideas and interests to be reflected in policy without contesting elections. The NoVa group members knew that the long-term success of American Muslims in politics would rely heavily on alliances and partnerships with candidates of other faiths and no faith, along with and until a cadre of American Muslims entered the political fray.

The group understood that true success with any political candidate would hinge on broad, authentic, and long-term policy alignment. They sought genuine relationships with the broader political landscape outside of the circumscription of party alliance or “Muslim issues,” based on shared humanity and as concerned citizens. Importantly, the NoVa group believed in honoring the long-standing existing relationships between several supportive Virginia politicians and the local American Muslim community, where there was true harmony of values and policy issues. The group also recognized that as Muslims, it was important to support candidates from other minorities who championed the causes that benefit underserved communities statewide, Muslim or otherwise. As such, the NoVa group sought to expand the network of American Muslim political influence and not to replace the existing network.

As veterans of American Muslim organizations, NoVa group members had observed the failure of community groups to connect meaningfully with political candidates and public officials solely on the basis of perceived “Muslim” foreign policy issues. In reality, American Muslims’ main policy interests pertain most often to domestic issues such as the economy, jobs, civil liberties, and education. The NoVa group members resolved to center their commonalities with the greater society as they began to create a platform for American Muslims, while still keeping in mind their unique investment in foreign policy matters.

The NoVa group created a business association as their first step. As a 501(c)6 nonprofit organization, a business association or chamber of commerce can engage in political activities such as mobilizing and lobbying. According to the Internal Revenue Service, “a business league is an association of persons having some common business interest, the purpose of which is to promote such common interest and not to engage in a regular business of a kind ordinarily carried on for profit. Trade associations and professional associations are business leagues. To be exempt, a business league’s activities must be devoted to improving business conditions of one or more lines of business as distinguished from performing particular services for individual persons. […] Seeking legislation germane to the common business interest is a permissible means of attaining a business league’s exempt purposes.”

As minority business owners, job creators, and corporate tax payers, NoVa group members were interested in candidates’ economic, labor, trade, and immigration policies. The NoVa group’s business association hired staff to research lawmakers seeking reelection, scrutinize new candidates, and analyze various candidates’ platforms. The business association staff could then make recommendations about candidates with potential commonalities or support candidates based on established track records and points of policy alignment. The business association also formed alliances with other ideologically aligned minority groups to undertake lobbying activities. As such, meetings conducted through the business association allowed NoVa group members to relate to other minority groups as well as politicians on several policy issues. NoVa group members found it much easier to meet with politicians on the basis of economic policy concerns than as special interest groups as a minority faith community. However, as American Muslims, they were also interested in candidates’ voting records on domestic and international issues of interest to the community. Where appropriate, they brought up regressive violations of civil rights or social policies that hindered their ability to contribute to the state’s economy.

NoVa group members took care to pour effort into morally and politically sound alliances for the best chance of success. For each candidate, they studied policy platforms and voting history to ensure alignment on issues of impact, gauged whether the candidate was viable, if their support for a candidate would be impactful for the causes important to the group, if the candidate would scale through their career, and whether the NoVa group and the American Muslim community could have a long-term relationship with the candidate. Through this process over a period of time, relationships between local politicians and the NoVa group grew based on genuine common interests and values. The following excerpt by one of the NoVa group’s volunteers touches upon the candidate selection process:

“Community members would get together and meet with various candidates to determine who would be a good fit. [They] chose candidates that shared mutual care and ensured that candidates and the community were on the same page. The relationship with candidates would be mutually beneficial and based on shared values.”

Respondent 4, phone interview, November 2019

Notably, as a matter of principle, the NoVa group did not favor a candidate merely on the basis of faith. As community members invested in the greatest good possible, they partnered with candidates based on their intentions for service. As venture capitalists, they invested in individuals with the greatest potential to scale and yield long-term beneficial results for the larger community.

The goal of serving the greater American Muslim community guided all political efforts of the NoVa group undertaken as a trade association. The trade association facilitated meetings between candidates and the Virginian Muslim community where community members and candidates were able to consort. As trusted community leaders, the NoVa group’s own positive relationships with politicians informed the opinions of their associates in the broader Virginian Muslim community as well.

2. Collective Capital

A key objective of the creation of the NoVa group was the establishment of a pool of financial resources. Concurrent with the creation of the business council, the NoVa group secured a sustainable stream of financial resources from within the group itself and a few other like-minded American Muslim contributors, as part of their venture capitalist approach to support local candidates. The core group members each committed to making an annual contribution of a sum of money toward the group’s civic and political goals. Indeed, the very core of the NoVa group coalesced around the individual members’ ability to contribute financially.

The group’s vision for this collective capital was a departure from the prevailing American Muslim campaign contribution habits in several important ways. First, the group understood that the effect of their combined monetary power would reach farther than individual contributions. Second, NoVa group members believed in the investment of American Muslim donations into multiple campaigns rather than a single contest, with donations made after selecting compatible and strategic local campaigns where the resources would have maximum impact. Third, the collective contribution method would be fundamentally different from past campaign contributions and remove personal links to monetary contribution—the NoVa group made collective rather than individual donations to highlight the American Muslim community as a whole and to foster community-candidate relationships rather than donor-candidate ones. Fourth, the NoVa group members were keen not to be recognized or commended as the architects or donors of this strategic push. The following quote from an interview respondent explains the group’s point of view regarding collective capital:

“The main point is to find people who can go beyond the ego of themselves donating the money for personal glory and can be part of a group effort and benefit minorities or our Muslim community as a whole.”

Respondent 3, phone interview, October 2019

Levers of Effective Local Political Engagement

The NoVa group understood that the three main variables or levers that can affect American Muslims’ impact on local races and change their representation in the political sphere are votes, financial support for candidates, and American Muslim volunteers in candidates’ campaigns. The group sought to change the way these levers have traditionally been used by American Muslim communities, so as to maximize change.

1. Votes

The NoVa group noted that while extremely important in their own right, the voting numbers of American Muslims alone are not influential in the outcome of national elections. Even in swing states, American Muslims cannot change national election results due to their relatively small numbers. Yet, politically engaged American Muslims are most enthused to participate in national elections and less for down-ballot races where their votes may hold more weight. Moreover, given the relatively small population of American Muslims, the cost-to-benefit ratio of increasing voting output is relatively high even for local contests. Still, when the NoVa group decided to support a local candidate, they mobilized community support for candidates in public and private American Muslim spaces such as mosques and homes, hosted candidate forums, held meet-and-greet gatherings, and canvassed. Through such events the community cultivated authentic relationships with candidates and allowed candidates to become more familiar with issues important to the American Muslim community. In addition to improving American Muslim voter turnout in local races, these efforts demonstrated that the community represented by the NoVa group honored and maintained relationships with their allies.

The NoVa group was mindful not to damage existing relationships in the pursuit of their goals for the American Muslim community. Although the group aimed to create a generation of American Muslim leaders and, ultimately, political candidates, their efforts were directed toward spaces where there was an absence of the reflection of American Muslims’ policy interests. If an existing candidate shared and represented the same concerns as the Virginian Muslim community, the community would lend support to that individual rather than using finite resources to shore up an American Muslim contender. By following this principle, they encouraged American Muslims to respect and protect established relationships and were able to conserve limited resources.

2. Strategic Financial Support

Once the NoVa group vetted candidates as minority business owners and American Muslim community members, they deployed their collective financial resources strategically across different viable candidacies rather than investing in one race. The group’s efforts focused on state contests as opposed to national elections. The following interview quote from a NoVa group member demonstrates the rationale behind strategic use of donations and how it could have a widespread and long-term impact on American Muslims:

“[If you raise $3 million,] You take that $3 million and spread it across 40 different races and [American Muslim] workers across those different races.… You’re betting on 40 people and not one person. You’re energizing a whole set of people. Those 40 people will have a hundred different relationships. You are solidifying 4,000 relationships. Real relationships are when people can rely on those people five to ten years later, too.”

Respondent 2, phone interview, September 2019

Further, the group supported candidates early on in the contest when monetary contributions were scarce and much needed, knowing that even smaller donations are impactful in the early months of a political campaign. In the following interview excerpt, a respondent who is part of the NoVa group explains how the form and timing of financial contributions make a difference:

“If you put $50,000 in a presidential campaign, it would be a drop in the bucket, but in a local race in Virginia, raising $50,000 is basically the same thing because it is the same ballot, but that same amount is more noticeable and impactful.”

Respondent 3, phone interview, October 2019

At times, the monetary contributions would strengthen community-candidate relationships by being directed toward fulfilling a campaign’s staffing needs. Since the NoVa group backed candidates based on careful selection and relationships with the community, they could leverage their understanding with candidates for a commitment to the diversification of their teams to reflect the diversity of their supporters. During the formative period of a campaign, they were able to offer funding for staff and volunteers, as well as recommend suitable picks from within the American Muslim community. As such, the NoVa group utilized community financial resources not only to support a candidate but also to create an opportunity for American Muslims to gain important real-world political experience while helping their faith and statewide community.

3. Volunteers

To build on the core principle of the development of a talent pipeline so that American Muslims could enter civic life, the NoVa group employed a two-pronged strategy for volunteers. First, they began important conversations within the American Muslim community to change mindsets around volunteerism, public service, and politics as viable careers for young adult American Muslims. Second, they set out to match vacancies with vetted volunteer candidates to enable civic engagement. The following interview quote shows that NoVa group members understood that the problem would need to be solved from a number of different angles:

“We realized we needed…to get qualified people running for office but to also support allies who are running for office. And we needed to make a very different effort to get young people into the system as staffers, active in campaigns, and in civil service.”

Respondent 3, phone interview, October 2019

The group’s call to volunteer and serve the broader community was rooted in Islamic teachings of khidmat—service to humanity without expectation of return. NoVa group members themselves stepped up to serve on several state boards even as they incurred personal costs—as business owners, they could no longer conduct business with a state board on which they served. However, their desire to serve the people of their state outweighed financial concerns. At the same time, the group worked to change American Muslim attitudes about careers in politics. Immigrant American Muslims generally tend to avoid public scrutiny and by extension, overt political activity. The American Muslim community’s long-term and effective political engagement would require a paradigm shift, where the community would view political engagement as a way of life.

Additionally, the group took concrete steps to aid American Muslims’ entry into public service. The NoVa group’s business association staff studied vacancies on citizen-volunteer boards at local, city, and state levels across Virginia. Then, they attempted to match qualified candidates to fill them. NoVa group members relied on personal contacts, networks, and recommendations to find potential volunteers from within the American Muslim community who could serve on such boards. The group identified and vetted candidates who possessed a set of unique capabilities. Instead of matching professional skills with tasks, the group sought candidates who had demonstrated integrity of character, high degrees of motivation, the ability to learn, and an attitude of service.

The group encouraged experienced mid-level professionals deemed suitable for public office to fill service-oriented public positions. Similarly, they encouraged young adult American Muslims to volunteer in candidates’ campaigns. They connected vetted, qualified, reliable, and intelligent American Muslim talent with candidates with the understanding that their recommendations would only translate into appointments on the basis of merit. The Nova group leveraged their unique position in the community to facilitate the training and mentoring of American Muslim talent with a view to their advancement in public service.

.

Results, Sustainability, and Future

Over the last several years, the NoVa group’s efforts have borne fruit in multiple ways. Some of the success stories are included below.

Results

Civic Engagement

Citizen-volunteers form the base of the pyramid of political engagement as imagined by the NoVa group. At the beginning of the group’s organized effort, their staff recorded fewer than 10 board positions filled by American Muslims across the state. As of 2020, by the NoVa group’s estimate, Muslims in Virginia currently serve on nearly 100 civic boards at city, county, and state levels. American Muslim volunteers are framing concerns about healthcare, human rights, unemployment, and racial discrimination, among others, into meaningful advocacy. In Virginia, Muslims now represent thousands of citizens and supervise the activities of hundreds of organizations. Their involvement includes the local Human Rights Commission, Department of Medical Assistance Services, Asian Advisory Board, Virginia Real Estate Board, Funeral Home Board, and professional association boards for physicians, dentists, nurses, and lawyers. Interview respondents state that at least three county commissioners in the state are Muslim and that Muslims are represented in multiple school boards, city councils, and boards of trustees of higher education institutions and community colleges.

The impact of influencing policies and improving society in material ways through service on civic boards is immense. For instance, by serving on the Department of Medical Assistance Services, American Muslims have been part of an initiative to partner with the Virginia Department of Education and the United States Department of Agriculture to offer free meals to an additional 500,000 impoverished children at no extra cost to the state. Similarly, American Muslim volunteers have been able to affect Medicaid expansion through the board and serve an additional 400,000 adults in Virginia.

Appointments

In recent years, American Muslims have been appointed to a number of statewide positions including Atif Qarni as Secretary of Education, Mona Siddiqui and Abrar Azamuddin as Assistant Attorney Generals, Asif Bhavnagri as the Assistant Secretary of Administration, and Meryem Karad as the Policy Advisor for the Secretary of Natural Resources.

The appointment of Atif Qarni as Virginia Secretary of Education by Governor Ralph Northam showcases the NoVa group’s planning in action. Atif Qarni moved to Virginia in 2005. He served in the United States Marine Corps and worked as a paralegal in an international law firm before beginning a career as a teacher of civics, U.S. history, and mathematics. The NoVa group recommended Atif as a campaign volunteer for several local races over the years until 2013, when Atif contested for a seat for the Virginia House of Delegates. In 2015, Atif attempted a run for the Virginia Senate, but lost again, despite being supported by the NoVa group. However, his presence in the civic arena and his volunteer and service experience left a mark on those he worked with.

In 2018, Atif Qarni became a member of the Virginia Governor’s Cabinet as Secretary of Education. Atif now heads the operations of the Education Secretariat, which “provides guidance to the Virginia Department of Education (VDOE), the Virginia Community College System (VCCS) and The State Council of Higher Education for Virginia (SCHEV), as well as Virginia’s 16 public colleges and universities, 23 community colleges and five higher education and research centers. We also provide support to seven state-funded arts/cultural institutions.” According to one NoVa group interview respondent, despite his electoral losses, overall Atif Qarni’s story is that of success as he demonstrates the power of volunteerism and service, is able to earn a living through public service, and is well positioned to be a force for positive change statewide.

Elections

In the year 2019, Virginia elected eight American Muslim officials, the most of any other U.S. state. The current Secretary of Education in Virginia, Atif Qarni, is an American Muslim that the NoVa group supported as a Democratic candidate since the beginning of his political career in 2013. In 2014, the NoVa group backed Sam Rasoul, who was elected to the Virginia House of Delegates. American Muslim attorney generals, secretaries of various governmental departments, and policy advisors across state government are now not uncommon in Virginia.

The following is a list of successful candidates in the 2019 elections:

- Buta Biberaj, Loudoun County Commonwealth’s Attorney

- Ghazala Hashmi, Senate District 10

- Babur Lateef, Prince William County School Board (reelection)

- Harris Mahedavi, Loudoun County School Board

- Abrar Omeish, Fairfax County School Board

- Sam Rasoul, House of Delegates District 11 (reelection)

- Ibraheem Samirah, House of Delegates District 86 (reelection)

- Lisa Zargarpur, Prince William County School Board

Talent Pipeline

Several political campaign volunteers and staffers appointed through the NoVa group’s efforts have risen to national recognition. For instance, Zaki Barzinji, a young adult Muslim from Virginia was initially recommended by the NoVa group as a staffer for gubernatorial candidate Terry McAuliffe. Zaki went on to be appointed as technology policy advisor and then as deputy director of intergovernmental affairs for Governor Terry McAuliffe. He subsequently became senior associate director of public engagement and served as the White House liaison to Muslim-American communities and other faiths. The support and relationship of the NoVa group for candidate McAuliffe facilitated Zaki Barzinji’s entrance into public service. In the span of a few years, Zaki progressed from being a campaign staff member to a White House appointee.

Similarly, through the NoVa group, Adnan Mohamed began his political career working as a campaign volunteer for Tom Perriello in Virginia. He joined Ralph Northam’s gubernatorial campaign in Virginia next, and was later picked by Massachusetts’ Seth Moulton campaign. In 2019, Adnan became national political director for the presidential campaign of Beto O’Rourke and subsequently served as the Virginia political director for the presidential campaign of Michael Bloomberg. The cases of Zaki Barzinji and Adnan Mohamed illustrate the success of the NoVa group’s strategic model: when vetted and well-matched talent are recommended to local candidates with whom strong, authentic personal and financial relationships have been nurtured, new avenues of political representation open up for American Muslims.

Sustainability

According to one NoVa group interviewee, over the years several American Muslim candidates have emerged organically and won city council and school board positions. The emergence and success of individuals and campaigns independent of the assistance or even knowledge of the NoVa group demonstrates the scalability and sustainability of the NoVa group’s model. In Virginia, the individual cost to enter the political arena is much lower for new entrants as politicians and voters are no longer fazed by minority candidates and are familiar with the American Muslim community.

The NoVa group’s activities at the state level have inspired the creation of at least one more strategic group in Virginia. In the state capital, Richmond, a number of American Muslims organized and developed strategic alliances with Democratic nominees following the 2016 presidential election. In the years following the election of President Donald Trump, American Muslims in Richmond cultivated interfaith alliances and partnerships with other minority organizations and compatible local political groups and candidates. They mobilized the local American Muslim community for like-minded candidates for local elections. They have mobilized community members to develop and nurture a strong relationship with Delegate Sam Rasoul and fundraise for him annually since his election to the Virginia House of Delegates in 2014. In 2019, the Richmond organizers strategized a zealous grassroots campaign for Ghazala Hashmi, helping her win the primary, and then continued to organize and support fundraising and canvassing activities to elect Ghazala Hashmi from the 10th District to the Senate of Virginia. The Richmond group has also started to develop alliances with Secretary of Education Atif Qarni since his appointment in 2018 and Delegate Ibraheem Samirah since his election in 2019. The Richmond organizers continue to refine their strategic vision and growth plans.

Future

The core NoVa group members view their role to be of an initial catalyst and for their success to be reflected in the ongoing increase in organic civic engagement within the American Muslim community. In many ways, the NoVa group members have achieved their goal and the fruits of their labor are clearly manifested in the high civic and political engagement levels among Muslims in the state of Virginia. Still, group members remain committed to furthering their cause to empower American Muslims to serve their country and participate in civic and political processes more fully. NoVa group members also wish to assist other American Muslim communities in tapping into their local talents and abilities to recreate the bottom-up success of Virginia through advisory activities.

One of the ways the NoVa group has undertaken steps to plant the seeds of future civic engagement and social understanding is through the Minority Student Leadership Program. Through this program, the group brings inner city and suburban youth together to nurture relationships that cross socioeconomic lines, in an effort to erase the disconnect between the separate worlds the two disparate groups inhabit and to build social and emotional intelligence. The group aims to promote leadership skills, build resilience, and nurture coalitions and alliances for common causes.

.

Challenges and Room for Improvement

Challenges

Interview respondents from both the NoVa group and the Richmond organizers encountered significant challenges as they embarked on their plan to address the lack of political representation of American Muslims. Entrenched views and attitudes of the American Muslim community emerged as the biggest obstacles organizers faced. The three main themes of these challenges are outlined below.

1. Voter Apathy

The NoVa group and the Richmond organizers noted widespread voter apathy among American Muslims. Cynicism and lack of trust in the political process have been a significant challenge to American Muslims’ political engagement. According to ISPU’s 2016 American Muslim Poll, of the American Muslims who didn’t vote, 36% were disenchanted with the candidates or felt that their vote didn’t make a difference. As many as 16% of American Muslims who are eligible to vote do not plan to participate in elections, the largest of any faith group polled by ISPU in 2020. Among those American Muslims willing to participate in the electoral process, an ideological divide exists along generational lines. Older immigrant American Muslims, arguably with a model minority mindset, tend to support establishment candidates and shy away from radical changes or supporting new candidates, even American Muslim ones. Politically active second- and third-generation American Muslims are more comfortable in their American identity and feel empowered to speak out against discrimination and support bold candidates.

2. Individual vs. Collective Glory

At an individual and organizational level, the NoVa group was challenged by donors’ and organizers’ reluctance to contribute to campaigns without individual recognition. The prevalent trend in American Muslim communities is to regard personal and family connections to a candidate as more valuable than the collective relationship of the community to a candidate. A desire for personal benefit and the keenness to be esteemed by a politician lead donors to enter into shallow and transactional relationships with political leaders that are ultimately ineffective. This tendency not only hinders the creation of a collective pool of substantial financial resources needed to effectively back campaigns, but also negates the principle of mutually beneficial partnerships that the NoVa group seeks to establish. According to interview respondents, in order to preserve the flow of financial contributions, members of the NoVa group take measures to ensure that donors feel valued and connected to the candidates and causes their financial resources support. However, doing so adds another layer of complexity to accomplish the task at hand.

In addition, the NoVa group experienced attention-seeking behavior by national level American Muslim organizations that claimed to have organized American Muslim support and took credit for the success of candidates of other faiths being supported by American Muslims. Oftentimes, such falsely attributed alliances embarrass candidates and create distance between true allies due to the spread of misinformation and misaligned goals. For a group that is keen to remain behind the scenes and foster natural relationships, such public proclamations by American Muslim organizations create confusion and prove detrimental to the NoVa group’s cause.

3. Attitudes Disfavoring Public Service Careers

The NoVa group and the Richmond organizers were both confronted by negative community-wide attitudes toward careers in public service and policy. The professional expectations of the older generation of American Muslims and the community’s bias against political careers significantly limited the NoVa group’s ability to find and mentor young American Muslim professionals who were suitable for campaigns that were looking for staff. Part of the NoVa group’s efforts within the community revolve around educating American Muslims about the lack of their representation in government, the ramifications of the absence of American Muslims voices in politics, and the importance of diverse career choices. One interview respondent explained voter apathy and career challenges in the following excerpt:

“I expected the younger generation to be more open to these ideas, but apathy exists at all levels. Young people were cynical about the political process themselves. They have different sets of issues that deter them from participation. And the older generation’s professional expectations from younger generations are also an issue that impacts the talent pipeline.”

Respondent 1, phone interview, July 2019

Room for Improvement

The NoVa group’s plan has met with remarkable success: in the 2019 elections, the Commonwealth of Virginia elected more American Muslim officials than any other state—no doubt in part due to the group’s concerted and sustained efforts. Still, improvements can be made to this model in order to realize even stronger results.

1. Diversity

The core of the strategic NoVa group consisted of men of South Asian and Arab descent at its inception. None of the original members of the group were women or Black. In the beginning, NoVa group members had personal connections with one another and naturally gathered around their ability to make consistent monetary contributions toward the collective capital project, which inadvertently excluded many other minority groups. According to NoVa group members, the demographic of the initial group is reflective of the American Muslim community of the area rather than an attempt to exclude diverse voices. Over the years, the group has taken steps to recruit volunteers from different backgrounds and recommended them for positions in campaigns. The group has also compensated for the lack of ethnic and racial diversity within their immediate American Muslim community by partnering with and supporting ethnically and religiously diverse candidates for delegate, mayoral, school board, county, and city races. However, including a variety of different voices in the group’s own overarching strategic planning process, as well as in execution, is critical to communicate the desires of the community holistically and lends important nuance to the movement.

2. Comprehensive Strategy

The structure and strategy of the NoVa group remain nebulous outside of their business association. The NoVa group have not codified their stance on specific policy issues, identified core advocacy areas, or developed concrete steps for a reliable talent pipeline and leadership development. As such, processes and strategy are still reliant on personal motivation, individual contacts, and trial and error. Though this lack of structure and fluid strategy arguably allows for greater adaptability, it may not be helpful guidance for other groups of American Muslims who lack the cohesion of the NoVa group to replicate its success.

.

Lessons Learned

1.Set Tangible Goals

While political and civic engagement by a community is relatively ambiguous and difficult to measure accurately, political representation at various levels of government is readily observable by numbers. For a community organization-led push to increase political representation to be effective, it is important for the strategic plan to include tangible goals by which to measure progress. It is not necessary to share them with the community at large, but goals should exist to provide a unifying vision to those involved in the effort. The goals can include a desired number of political representatives, American Muslims working at a certain level of government, or achievement of a given milestone by a certain time. For the NoVa group, setting a goal to have an American Muslim representative at the state level by the year 2017 animated the strategies and systems it subsequently designed and deployed. Currently, the group continues to create programming to reduce the cost of entry into the political arena for each subsequent American Muslim candidate.

2. Develop a Strategy and Supportive Systems

In order to achieve stated goals, a clear strategic plan is fundamental to the development of pathways to success.

- Strategy – For the NoVa group, authentic relationships, mutual understanding, and collective capital investment were the fundamental guiding principles of all further measures taken by the group.

- Systems – The NoVa group created two core systems to achieve their goals—a professional association to enable and assist their relationship-building endeavors and lobbying, and a stream of collective capital through a group of donors to support political campaigns.

3. Use Levers of Local Engagement Strategically: Votes, Investment, and Volunteers

Three main inputs required by a political campaign are votes, financial contributions, and volunteer manpower. To effectively leverage a community’s influence on a local election, it is necessary to be familiar with the unique advantage the community’s support can lend a candidate. Knowing these three levers, the NoVa group identified their community’s strength and utilized it to maximum advantage. Given the community’s marginal numbers in terms of population, the key lever used by the NoVa group was financial contributions used strategically to back a number of viable candidates. The collective contributions were made on behalf of the entire local American Muslim community early on in local contests when cashflow is crucial for candidates. In terms of volunteers, the NoVa group recommended quality volunteer candidates for campaigns, which facilitated American Muslims’ input in candidates’ policies and understanding of minority concerns. In addition, once committed to a race, the NoVa group would also mobilize American Muslim voters and advance further community-candidate relationships.

4. Undertake Community Outreach and Education

Community buy-in and support are fundamental to the long-term success of an initiative to increase political representation. No matter how great the vision and plan, a small group of leaders or organizers cannot bring forth community-wide change on their own. The NoVa group worked to dismantle community donors’ deep-rooted desire to make monetary contributions for personal gain and recognition and also educated them about the merits of collective action. Similarly, they confronted their community’s negative attitudes regarding careers in public service and encouraged young and mid-career American Muslim professionals to pursue careers in politics and take up positions in public service.

5. Conduct Analysis and Reflection

The NoVa group’s very inception was the result of a group of concerned community members’ self-reflection after a spirited election cycle. The formation of the NoVa group and the Richmond organizers and their subsequent success are testaments to the power of self-analysis at a critical moment by community leaders. However, reflection at each step of engagement and after each election cycle must occur. Such analysis can not only spur innovation and prevent stagnation but is also necessary for the continuous improvement of strategies, processes, and results. The NoVa group has continued to learn and refine their approach with each candidate and race.

6. Create Avenues for Sustainability of Vision

Short-term goals have been a major pitfall of earlier efforts to boost American Muslim political engagement. In order to create an effective ecosystem and a self-sustaining cycle of civic and political engagement and involvement, American Muslims must have sustained involvement in civic engagement through various activities across organizations, communities, and candidates, irrespective of election cycles. The NoVa group has created programming for youth to bring together disparate community members with a view to create understanding, solve mutual problems, and sow the seeds of future civic engagement. NoVa group members also aim to standardize and disseminate best practices with other American Muslim communities to achieve widespread and true American Muslim political representation at the national level.

.

Timeline of Recent Noteworthy American Muslim Electoral Achievements

In the State of Virginia and at State Level Nationwide

The following timeline does not claim to capture all the political engagement work done on behalf of the American Muslim community, which dates back many decades. A proper illustration of this rich history is beyond the scope of this case study. We have instead selected to begin the timeline with the first Muslim elected to Congress as a starting point and end with the most recent statewide successes elsewhere in the country. This timeline does not reflect the efforts of the NoVa group exclusively.

2007

Keith Ellison (MN) elected as first Muslim Congressman

2008

André Carson (IN) elected as second Muslim Congressman

American Muslims organize for Obama campaign. Mobilization includes groups of older civically engaged American Muslims, as well as second-generation Muslims who have benefited from legacy organizations and are invested in U.S. politics.

2010

NoVA group creates strategy for the state of Virginia and sets up business association. Some of the candidates selected for support in the following years include Brian Moran, Creigh Deeds, and Terry McAuliffe.

2014

Sam Rasoul elected to Virginia House of Delegates

2016

Richmond group mobilizes to increase civic engagement among Richmond-area Muslim communities.

2017

Richmond group mobilizes grassroots support and organizes fundraising events for Ralph Northam for governor and Mark Herring for attorney general.

2018

Richmond group mobilizes grassroots support and organizes fundraising events for Abigail Spanberger for U.S House of Representatives and Tim Kaine for U.S. Senate.

Rashida Tlaib (MI) elected to U.S. Congress as the first woman of Palestinian heritage to hold statewide office

Ilhan Omar (MN) elected to U.S. Congress as the first Somali-American woman to hold this office

2019

Richmond group mobilizes zealous grassroots support for Ghazala Hashmi during her primary campaign and election and collaborates with NoVa group to expand Virginia Muslim support for Ghazala Hashmi.

Ghazala Hashmi from Richmond, VA, elected to Virginia Senate from the 10th District

Ibraheem Samirah elected to Virginia House of Delegates

.

Sources

Muslims and Politics

Emgage USA, “2018 Midterm Muslim Voter Turnout.”

Pew Research Center, “Faith on the Hill: The Religious Composition of the 116th Congress,” January 3, 2019.

Andrea Elliott, “White House Quietly Courts Muslims in U.S.,” New York Times, April 18, 2010.

Cision PR Newswire, “CAIR, Jetpac, MPower Change: 26 American Muslim Candidates Win in Nov. 5 Elections for Total of 34 Muslims Elected in 2019,” November 6, 2019.

Dalia Mogahed and Fouad Pervez, American Muslim Poll 2016: Participation, Priorities, and Facing Prejudice in the 2016 Elections (Institute for Social Policy and Understanding, 2016).

Dalia Mogahed and Erum Ikramullah, American Muslim Poll 2020: Amid Pandemic and Protest (Institute for Social Policy and Understanding, 2020)

State Demographics

Public Religion Research Institute, “The American Values Atlas.”

Muslims in Virginia

Salatomatic, “Mosques and Islamic Schools in Virginia.”

Pew Research Center, “Religious Landscape Study: Muslims.” (Estimates that in 2014, 1% of adults in Virginia were Muslim)

Leadership in Social Change Organizations

Research Center for Leadership in Action, How Social Change Organizations Create Leadership Capital and Realize Abundance amidst Scarcity (NYU Wagner).

IRS 501(c)6 Designation

Internal Revenue Service, “Business Leagues.”

Virginia Policies and Initiatives

Virginia Department of Education, “School Nutrition: Programs, Promotions and Initiatives.”

Cover Virginia, “Virginia’s New Health Coverage for Adults.”