.

Countering Anti-Muslim Opposition to Mosque and Islamic Center Construction and Expansion

Recommendations for mosque leaders, policymakers, interfaith and community allies, and more

May 23, 2022 | BY DR. ELIZABETH A. YATES AND AZKA MAHMOOD

SUMMARY

This toolkit offers recommendations and resources to understand, preempt, and challenge opposition to mosque and Islamic center construction and expansion. Because opposition to mosque construction can itself become an accelerant/driver of increased anti-Muslim organizing and narratives in communities, these recommendations also support leaders with preventing escalations in anti-Muslim narratives and organizing from taking hold in their communities.

.

Executive Summary

As a pluralistic society hosting a multitude of faiths, the ability of faith groups to worship, gather, and access faith-based services is critical in the United States. For American Muslims, that space is the mosque or Islamic center. Mosques offer Americans who are Muslims a place to gather for Friday congregational prayers, the obligatory five daily prayers, for Eid holiday worship services, and Ramadan iftars and nightly prayers. In addition to worship, American mosques and Islamic centers provide Muslims with a range of services, from youth and adult education, social services and counseling, community gatherings, and social clubs. And, mosques in America do not just benefit Muslims, they are good for democracy. ISPU’s American Muslim Poll 2016 finds that frequent mosque attendance is linked to higher levels of civic engagement and that Muslims with strong religious identities are more likely to have strong American identities.

Opposition to the construction and expansion of mosques and community centers for Muslims in the United States has been documented since the 1980s. The growth of the Muslim community in the U.S. and the emergence of more prominent and purpose-built dedicated places of worship made new mosques more susceptible to opposition. Since the 1980s and through to the present, mosques across the U.S. face anti-mosque activity, including arson, vandalism, break-ins, and hate activity. According to research, the last decade saw the highest levels of opposition to mosques and more than a quarter of mosques faced opposition to construction or expansion.

The Free Exercise Clause of the First Amendment protects citizens’ right to practice their religion. Federal Law Protections for Religious Liberty make it illegal to discriminate against individuals or groups based on religion. As such, the freedom to build houses of worship is enshrined within the U.S. Constitution. However, Islamophobia and bigotry persist and extend to the creation and use of spaces of worship by Muslims. There is evidence of coordinated efforts by anti-Muslim groups and individuals to oppose the construction and expansion of mosques under the guise of developmental concerns. In addition, a well-funded Islamophobia industry that spreads fear and deliberate misinformation about Muslims, biases in media and legal representation of Muslims, and a general lack of knowledge about Muslims and Islam create difficulty in parsing through real intentions behind opposition to mosques.

This toolkit offers recommendations and resources to understand, preempt, and challenge opposition to mosque and Islamic center construction and expansion. Because opposition to mosque construction can itself become an accelerant/driver of increased anti-Muslim organizing and narratives in communities, these recommendations also support leaders with preventing escalations in anti-Muslim narratives and organizing from taking hold in their communities.

Research Methodology

The Institute for Social Policy and Understanding (ISPU) and Over Zero analyzed 42 instances of mosque opposition and two in-depth case studies to unveil the dynamics of mosque opposition. We also analyzed a 2016 book titled Mosques in America: A Guide to Accountable Permit Hearings and Continuing Citizen Oversight, released by the Center for Security Policy, an organization founded by Frank Gaffney Jr., who the Southern Poverty Law Center deemed “one of America’s most notorious Islamophobes.” This book aims to equip zoning planners and citizens with tools to “confront” mosque construction. We reference the tactics recommended in this frequently used handbook with documented instances of mosque opposition.

Findings from a review of 42 instances of mosque opposition

- The timing of mosque opposition coincided with national flash point events such as the Park 51 mosque conflict and political cycles (e.g., the 2010 and 2016 midterm elections) with heightened anti-Muslim and anti-refugee rhetoric.

- Despite the national-level media sources and political organizing that drives Islamophobic and anti-shariah sentiment, conflicts over mosques are largely local affairs.

- Anti-mosque sentiments fall into two broad categories: anti-development arguments and anti-Muslim opposition. In our analysis, 30 of the 42 instances of mosque opposition studied showed explicitly anti-Muslim sentiments. It should be noted that anti-development arguments may also mask anti-Muslim opposition.

- A 2016 book released by the Center for Security Policy titled Mosques in America: A Guide to Accountable Permit Hearings and Continuing Citizen Oversight outlines how to oppose mosques using procedural and legal methods to obscure anti-Muslim intentions. The Center for Security Policy is a documented fixture of the Islamophobia industry according to the Southern Poverty Law Center. Local actors may be following a shared national script.

Recommendations

For mosque leadership:

- Build strong neighborhood relationships with businesses, residents, and civic associations surrounding the mosque and establish trust and channels of communication.

- Educate community members and leadership about possible mosque opposition strategies and narratives and local community history. In particular, familiarize yourselves with the tactics outlined in the 2016 book released by the Center for Security Policy titled Mosques in America: A Guide to Accountable Permit Hearings and Continuing Citizen Oversight. Share the book with close allies for their awareness.

- Preempt anticipated legal obstacles, for example, by selecting a parcel of land that does not require rezoning for mosque use.

- Assemble a strong team of experts from within and outside the Muslim community to undertake appropriate land acquisition and address any legal concerns.

- Retain the best possible legal representatives that befits the nature of the opposition and local setting of the dispute in case of opposition.

- Honor promises made to neighbors regarding land use, noise, and safety.

- Develop and offer a concrete path for addressing future grievances.

For interfaith and community allies:

- Build a coalition with community partners, including local businesses, houses of worship, and civic leaders to provide testimony in hearings and highlight the positive impact of diverse houses of worship.

- Build a strong interfaith coalition to stand together for religious freedoms and fairness and demonstrate unity and mutual respect.

- Avoid signaling negative norms. Specifically, avoid signaling that anti-Muslim narratives or opposition to mosque construction is the popular or dominant view. Signaling that something is the dominant sentiment can actually fuel participation and even discourage others from speaking out against it.

- Avoid inflammatory or dehumanizing language, as this helps escalate a conflict environment.

- Prepare coalition members for rapid response via public messaging, speaking out in support, or meeting with opposition, in case resistance to mosque arises.

- Create a messaging plan that utilizes the most effective messengers and channels.

- Use best practices to correct misinformation – be expedient, use positive framing, and avoid reinforcing stereotypes and giving false credence to opposition claims.

For city council members and policymakers:

- Build meaningful relationships with local Muslim communities and leadership.

- Establish direct channels of communication with local Muslims to collaborate and share information.

- Reach out to local Muslim communities and leaders to understand issues and confront misinformation.

- Understand the Islamophobia industry’s efforts to create fear of and resistance to mosques and Muslims.

- Learn about anti-Muslim agendas disguised as anti-development arguments for mosque opposition.

- Pursue factual information on the effects of diverse faith communities and the character and contribution of the local Muslim community.

For media:

- Get educated on covering Muslims objectively.

- Be aware of setting norms: avoid depicting opposition as more prevalent or widespread than it is. Instead, be sure to tell stories and include quotes from the local Muslim community and those working with them.

- Highlight the community’s self-declared positive values and identity rather than counter allegations made by opposition. Minimize negative associations made about the community. Remember that when you repeat/quote content that evokes stereotypes, dehumanization, etc., it creates increased familiarity and associations with them.

- Avoid inflammatory and dehumanizing language in reference to people so as not to trigger fear, hostility, anger, and retaliation that leads to greater inter-group divisions.

Introduction and Background

This toolkit is a resource for organizations seeking an understanding of the dynamics of anti-Muslim organizing and narratives in opposition to efforts to build or expand mosques and Islamic centers. It focuses on developing an understanding of the challenge and how it manifests as well as providing case studies and suggestions for how communities can proactively navigate these dynamics to prevent anti-Muslim narratives and organizing from interfering/taking hold.

→ This toolkit deals with multiple manifestations of Islamophobia. For the purpose of this toolkit, “anti-Muslim” is operationalized to refer to individuals and organizations who, through their expressed ideas, advance negative stereotypes of Muslims and Islam, intentionally or otherwise.

Research conducted by ISPU found evidence that opposition to mosque construction and expansion in the U.S. dates back to the 1980s. Throughout the 1980s and 1990s, this opposition occurred alongside the growth of the U.S. Muslim community and the evolution of many mosques, from innocuous storefront centers to purpose-built dedicated places of worship, Islamic education, and community activities. These new mosques were more prominent, which made them more susceptible to opposition. Throughout this time and to the present, mosques across the U.S. also face anti-mosque activity, including arson, vandalism, break-ins, and hate-based acts.

Opposition to construction and expansion of mosques and Islamic centers occurs in a context where most Americans neither personally know a Muslim nor very much about Islam. This leaves room for a distorted view of Muslims rooted in negative stereotypes perpetrated by those in positions of power and the media. Indeed, biases in media and legal representation of Muslims have been found in research. Further, there is a well-funded Islamophobia industry that traffics in fear and deliberate misinformation about Muslims. Amidst this environment, some Americans are resistant to or confused about the growing Muslim community in the United States.

While there is ample evidence of a long and coordinated movement to manufacture bigotry and demonize Islam, the concerted effort to singularly push against the construction and expansion of mosques under the guise of developmental concerns renders it difficult to parse through the true intention behind opposition to mosque construction. Communities must educate themselves about the possibility of such pushback. Preparation, community engagement, and timely proactive measures can limit opportunities for opposition to fuel anti-Muslim sentiment or organize in the communities where mosques and Islamic centers are being built or proposed.

Methodology

ISPU collaborated with Over Zero to develop this toolkit. Researchers used a list of anti-mosque activity reports compiled and made publicly available by the ACLU, further information about these cases using online sources, two case studies conducted by ISPU, previous ISPU publications outlining best practices for urban planners and mosque officials when undertaking mosque construction or expansion, and analysis of the book Mosques in America: A Guide to Accountable Permit Hearings and Continuing Citizen Oversight by Karen Lugo, published by the Center for Security Policy.

-

- ACLU Dataset and public records: Over Zero researchers analyzed 42 instances of opposition to mosque construction or expansion that were compiled in a dataset by the ACLU for the years 2010 to 2018.1 Using publicly available information such as news reports, court records, public social media posts, and government documents (including minutes and video from public hearings, announcements, and statements from zoning boards, etc.), researchers identified and outlined the types and prevalence of narratives employed by mosque opposition groups.

- Case studies: ISPU researchers conducted interviews and compiled two case studies of community instances of mosque opposition and how they were addressed. The McLean Islamic Center in McLean, Virginia, and Rayyan Center in Plymouth Township, Michigan, were selected as examples for this toolkit.

- ISPU publications: Not in Our Neighborhood: Managing Opposition to Mosque Construction and Building Mosques in America: Strategies for Securing Municipal Approvals by Kathleen Foley were studied for recommendations on best practices.

- Center for Security Policy book: ISPU researchers studied Mosques in America: A Guide to Accountable Permit Hearings and Continuing Citizen Oversight, published by the anti-Muslim think tank Center for Security Policy. Through the analysis of this book, we underscore the shared national script used by actors for mosque opposition and highlight where these tactics have been used in documented cases.

We envision this toolkit as a living document, to be updated as new research becomes available.

SUMMARY

This toolkit offers recommendations and resources to understand, preempt, and challenge opposition to mosque and Islamic center construction and expansion. Because opposition to mosque construction can itself become an accelerant/driver of increased anti-Muslim organizing and narratives in communities, these recommendations also support leaders with preventing escalations in anti-Muslim narratives and organizing from taking hold in their communities.

DOWNLOADS

Executive Summary

Opposition to the construction and expansion of mosques and community centers for Muslims in the United States has been documented since the 1980s. The growth of the Muslim community in the U.S. and the emergence of more prominent and purpose-built dedicated places of worship made new mosques more susceptible to opposition. Since the 1980s and through to the present, mosques across the U.S. face anti-mosque activity, including arson, vandalism, break-ins, and hate activity. According to research, the last decade saw the highest levels of opposition to mosques and more than a quarter of mosques faced opposition to construction or expansion.

The Free Exercise Clause of the First Amendment protects citizens’ right to practice their religion. Federal Law Protections for Religious Liberty make it illegal to discriminate against individuals or groups based on religion. As such, the freedom to build houses of worship is enshrined within the U.S. Constitution. However, Islamophobia and bigotry persist and extend to the creation and use of spaces of worship by Muslims. There is evidence of coordinated efforts by anti-Muslim groups and individuals to oppose the construction and expansion of mosques under the guise of developmental concerns. In addition, a well-funded Islamophobia industry that spreads fear and deliberate misinformation about Muslims, biases in media and legal representation of Muslims, and a general lack of knowledge about Muslims and Islam create difficulty in parsing through real intentions behind opposition to mosques.

This toolkit offers recommendations and resources to understand, preempt, and challenge opposition to mosque and Islamic center construction and expansion. Because opposition to mosque construction can itself become an accelerant/driver of increased anti-Muslim organizing and narratives in communities, these recommendations also support leaders with preventing escalations in anti-Muslim narratives and organizing from taking hold in their communities.

Research Methodology

The Institute for Social Policy and Understanding (ISPU) and Over Zero analyzed 42 instances* of mosque opposition and two in-depth case studies to unveil the dynamics of mosque opposition. We also analyzed a 2016 book titled Mosques in America: A Guide to Accountable Permit Hearings and Continuing Citizen Oversight, released by the Center for Security Policy, an organization founded by Frank Gaffney Jr., who the Southern Poverty Law Center deemed “one of America’s most notorious Islamophobes.” This book aims to equip zoning planners and citizens with tools to “confront” mosque construction. We reference the tactics recommended in this frequently used handbook with documented instances of mosque opposition.

Findings from a review of 42 instances of mosque opposition

- The timing of mosque opposition coincided with national flash point events such as the Park 51 mosque conflict and political cycles (e.g., the 2010 and 2016 midterm elections) with heightened anti-Muslim and anti-refugee rhetoric.

- Despite the national-level media sources and political organizing that drives Islamophobic and anti-shariah sentiment, conflicts over mosques are largely local affairs.

- Anti-mosque sentiments fall into two broad categories: anti-development arguments and anti-Muslim opposition. In our analysis, 30 of the 42 instances of mosque opposition studied showed explicitly anti-Muslim sentiments. It should be noted that anti-development arguments may also mask anti-Muslim opposition.

- A 2016 book released by the Center for Security Policy titled Mosques in America: A Guide to Accountable Permit Hearings and Continuing Citizen Oversight outlines how to oppose mosques using procedural and legal methods to obscure anti-Muslim intentions. The Center for Security Policy is a documented fixture of the Islamophobia industry according to the Southern Poverty Law Center. Local actors may be following a shared national script.

Recommendations

For mosque leadership:

- Build strong neighborhood relationships with businesses, residents, and civic associations surrounding the mosque and establish trust and channels of communication.

- Educate community members and leadership about possible mosque opposition strategies and narratives and local community history. In particular, familiarize yourselves with the tactics outlined in the 2016 book released by the Center for Security Policy titled Mosques in America: A Guide to Accountable Permit Hearings and Continuing Citizen Oversight. Share the book with close allies for their awareness.

- Preempt anticipated legal obstacles, for example, by selecting a parcel of land that does not require rezoning for mosque use.

- Assemble a strong team of experts from within and outside the Muslim community to undertake appropriate land acquisition and address any legal concerns.

- Retain the best possible legal representatives that befits the nature of the opposition and local setting of the dispute in case of opposition.

- Honor promises made to neighbors regarding land use, noise, and safety.

- Develop and offer a concrete path for addressing future grievances.

For interfaith and community allies:

- Build a coalition with community partners, including local businesses, houses of worship, and civic leaders to provide testimony in hearings and highlight the positive impact of diverse houses of worship.

- Build a strong interfaith coalition to stand together for religious freedoms and fairness and demonstrate unity and mutual respect.

- Avoid signaling negative norms. Specifically, avoid signaling that anti-Muslim narratives or opposition to mosque construction is the popular or dominant view. Signaling that something is the dominant sentiment can actually fuel participation and even discourage others from speaking out against it.

- Avoid inflammatory or dehumanizing language, as this helps escalate a conflict environment.

- Prepare coalition members for rapid response via public messaging, speaking out in support, or meeting with opposition, in case resistance to mosque arises.

- Create a messaging plan that utilizes the most effective messengers and channels.

- Use best practices to correct misinformation – be expedient, use positive framing, and avoid reinforcing stereotypes and giving false credence to opposition claims.

For city council members and policymakers:

- Build meaningful relationships with local Muslim communities and leadership.

- Establish direct channels of communication with local Muslims to collaborate and share information.

- Reach out to local Muslim communities and leaders to understand issues and confront misinformation.

- Understand the Islamophobia industry’s efforts to create fear of and resistance to mosques and Muslims.

- Learn about anti-Muslim agenda disguised as anti-development arguments for mosque opposition.

- Pursue factual information on the effects of diverse faith communities and the character and contribution of the local Muslim community.

For media:

- Get educated on covering Muslims objectively.

- Be aware of setting norms: avoid depicting opposition as more prevalent or widespread than it is. Instead, be sure to tell stories and include quotes from the local Muslim community and those working with them.

- Highlight the community’s self-declared positive values and identity rather than counter allegations made by opposition. Minimize negative associations made about the community. Remember that when you repeat/quote content that evokes stereotypes, dehumanization, etc., it creates increased familiarity and associations with them.

- Avoid inflammatory and dehumanizing language in reference to people so as not to trigger fear, hostility, anger, and retaliation that leads to greater inter-group divisions.

INTRODUCTION AND BACKGROUND

This toolkit is a resource for organizations seeking an understanding of the dynamics of anti-Muslim organizing and narratives in opposition to efforts to build or expand mosques and Islamic centers. It focuses on developing an understanding of the challenge and how it manifests as well as providing case studies and suggestions for how communities can proactively navigate these dynamics to prevent anti-Muslim narratives and organizing from interfering/taking hold.

→ This toolkit deals with multiple manifestations of Islamophobia. For the purpose of this toolkit, “anti-Muslim” is operationalized to refer to individuals and organizations who, through their expressed ideas, advance negative stereotypes of Muslims and Islam, intentionally or otherwise.

Research conducted by ISPU found evidence that opposition to mosque construction and expansion in the U.S. dates back to the 1980s. Throughout the 1980s and 1990s, this opposition occurred alongside the growth of the U.S. Muslim community and the evolution of many mosques, from innocuous storefront centers to purpose-built dedicated places of worship, Islamic education, and community activities. These new mosques were more prominent, which made them more susceptible to opposition. Throughout this time and to the present, mosques across the U.S. also face anti-mosque activity, including arson, vandalism, break-ins, and hate-based acts.

Opposition to construction and expansion of mosques and Islamic centers occurs in a context where most Americans neither personally know a Muslim nor very much about Islam. This leaves room for a distorted view of Muslims rooted in negative stereotypes perpetrated by those in positions of power and the media. Indeed, biases in media and legal representation of Muslims have been found in research. Further, there is a well-funded Islamophobia industry that traffics in fear and deliberate misinformation about Muslims. Amidst this environment, some Americans are resistant to or confused about the growing Muslim community in the United States.

While there is ample evidence of a long and coordinated movement to manufacture bigotry and demonize Islam, the concerted effort to singularly push against the construction and expansion of mosques under the guise of developmental concerns renders it difficult to parse through the true intention behind opposition to mosque construction. Communities must educate themselves about the possibility of such pushback. Preparation, community engagement, and timely proactive measures can limit opportunities for opposition to fuel anti-Muslim sentiment or organize in the communities where mosques and Islamic centers are being built or proposed.

Methodology

ISPU collaborated with Over Zero to develop this toolkit. Researchers used a list of anti-mosque activity reports compiled and made publicly available by the ACLU, further information about these cases using online sources, two case studies conducted by ISPU, previous ISPU publications outlining best practices for urban planners and mosque officials when undertaking mosque construction or expansion, and analysis of the book Mosques in America: A Guide to Accountable Permit Hearings and Continuing Citizen Oversight by Karen Lugo, published by the Center for Security Policy.

-

- ACLU Dataset and public records: Over Zero researchers analyzed 42 instances of opposition to mosque construction or expansion that were compiled in a dataset by the ACLU for the years 2010 to 2018.1 Using publicly available information such as news reports, court records, public social media posts, and government documents (including minutes and video from public hearings, announcements, and statements from zoning boards, etc.), researchers identified and outlined the types and prevalence of narratives employed by mosque opposition groups.

- Case studies: ISPU researchers conducted interviews and compiled two case studies of community instances of mosque opposition and how they were addressed. The McLean Islamic Center in McLean, Virginia, and Rayyan Center in Plymouth Township, Michigan, were selected as examples for this toolkit.

- ISPU publications: Not in Our Neighborhood: Managing Opposition to Mosque Construction and Building Mosques in America: Strategies for Securing Municipal Approvals by Kathleen Foley were studied for recommendations on best practices

- Center for Security Policy book: ISPU researchers studied Mosques in America: A Guide to Accountable Permit Hearings and Continuing Citizen Oversight, published by the anti-Muslim think tank Center for Security Policy. Through the analysis of this book, we underscore the shared national script used by actors for mosque opposition and highlight where these tactics have been used in documented cases

We envision this toolkit as a living document, to be updated as new research becomes available.

.

Recommendations to Counter Mosque Opposition

To effectively navigate and respond to opposition to mosques, community organizations and leaders can equip themselves with several key strategies. In this section, these strategies are organized into (1) land selection and education; (2) coalition building; and (3) responding strategically (communications and other preparatory steps). At the conclusion of this section, strategies are grouped as recommendations for specific stakeholders that deal with mosque opposition.

While the below discussion offers generalized recommendations, it’s critical that the strategies be tailored to local dynamics — the specific nature of the opposition and those involved, any community history of interfaith division or cooperation, and the messages, speakers, and approaches most likely to be effective within the concerned community.

Report Partners

This report was produced in partnership with Over Zero. Over Zero partners with community leaders, civil society, and researchers to harness the power of communication to prevent, resist and rise above identity-based violence and other forms of group-targeted harm.

ISPU and Over Zero would like to acknowledge our generous partners at the Democracy Fund, whose support made this report possible.

Research and educate yourself and your community

-

- Educate community members and leadership about possible opposition strategies and narratives to be positioned to anticipate, monitor, and mitigate such actions.

- Research community history. Learn whether the community has a history of tolerance, interfaith or cultural divisions, or other tensions and conflicts that might have arisen. Understand the actors and organizations involved in these dynamics — those who spread anti-Muslim messages or lead related efforts as well as those who have been active in pushing back and advocating for tolerance and inclusion.

Reduce legal obstacles and recruit expertise and representation

-

- Choose a parcel of land that does not require rezoning. Strive to build Islamic centers on land that is already zoned for houses of worship. In the case of Rayyan Center in Plymouth Township, MI, a rezoning request to allow a house of worship to be built was the main obstacle to mosque construction. Some strategies for selecting a parcel of land for a mosque to avoid conflict are outlined in the ISPU report, Building Mosques in America.

- Assemble a strong team of experts from within and outside the Muslim community to address land acquisition and legal challenges, including real estate experts, lawyers familiar with the nuances of local zoning ordinances and local land law, and other experts as deemed useful to preemptively circumvent or tackle foreseeable issues. With the McLean Islamic Center, a team of legal experts, structural engineers, water mitigation professionals, and zoning law experts from within the congregation studied and responded to opposition from all angles. This team should be from within the geographic community if possible.

- Retain the best possible legal representatives. Understand the character of the opposition and the local setting of dispute, and choose the best fit for legal representation. In the McLean case, choosing a nationally acclaimed and renowned large legal firm was appropriate. For Rayyan Center, a well-connected local attorney from a small firm was deemed a good fit for the problem at hand.

Build relationships and coalitions

-

- Build neighborhood relationships. Build trust and relationships with neighborhood businesses, residents, civic associations, houses of worship, and homeowners associations to create greater community buy-in and communication channels with different stakeholders. This should be done as early as possible in the process, possibly concurrently with land purchase. Maintain and grow these relationships over time. For instance, the McLean Islamic Center schedules quarterly picnics with their neighbors to cultivate friendship and provide an avenue to communicate.

- Build a community coalition. For public hearings and supportive testimony to highlight the positive impact of the presence of diverse houses of worship, mosque leadership and allies should cultivate and call upon community networks and coalitions. Employers, business owners, civic leaders, and other social service groups can underscore the benefits and value of diverse houses of worship in their surrounding area such as ease for their workers, reflecting diversity in the area, etc.

- Build a strong interfaith coalition. Connect with and support other faith leaders throughout the immediate and neighboring areas. Showcase unity and mutual support for one another’s places of worship, broader communities, and religious freedoms. When appropriate, coordinate messaging among intra- and interfaith leadership to demonstrate unity. For example, religious leadership from the Muslim community should connect with leaders of other faiths to stand together for religious freedoms and fairness. In addition, support from surrounding Islamic centers in the greater community is also necessary to portray a united community and showcase an engaged and peaceful Muslim presence. In particular, these coalitions should be well-represented at any public hearings and events.

Respond strategically: communications and preparatory considerations

Preparatory Considerations

-

- Prepare coalitions for rapid response. Recognizing that mosque construction or expansion may spark opposition–whether explicitly anti-Muslim or packaged as land use concerns–prepare your coalition to respond if and when resistance arises. Create a monitoring and rapid response plan to keep a pulse on any anti-mosque narratives or actions that are arising. Identify when it’s helpful or needed for trusted leaders within your coalition — other religious leaders, civic leaders, respected businesspeople, and other influential community figures — to address these sentiments, either through speaking out publicly in support of the mosque or in meeting with those spearheading the opposition.

- Recognize that communications involve more than a persuasive message. Effective communications demand more than a persuasive message; they must engage the right messengers and channels to reach and influence target audiences. When opposition arises, learn more about the groups among whom the anti-mosque messages are resonating. Identify trusted speakers who are influential among these audiences and support them in sharing messages across channels that will reach these audiences and undermine core anti-Muslim narratives. Equally if not more important is to identify a constellation of messengers that will be seen as signaling the norms and preferences of the broader community; this may mean activating across faith leaders, business leaders, other community members like teachers to make sure that the breadth and diversity of messengers shows broad community support.

Messaging Considerations

-

- Shape and amplify group norms. Individuals are powerfully influenced by what they perceive other group members are thinking or doing, even if this perception does not match reality. People are especially influenced by group leaders and members with a large number of social connections. Recognizing this, coordinate with influential group leaders across faith and other local communities to showcase how most community members support or at least do not oppose mosque development. As part of this, showcase how diversity and tolerance are deeply rooted in and have benefitted the given community. Throughout this, show and don’t just tell — model the norms of tolerance and interfaith cooperation you are hoping to amplify throughout the community. Stories of interfaith cooperation, friendship, and respect maybe especially powerful.

- Avoid signaling negative norms. In addressing any mosque opposition that does arise, be careful not to inadvertently depict such opposition as more widespread or prevalent than it is. For instance, rather than centering messages on opposition, highlight neighborhood support and appreciation for the Muslim community and religious diversity.

- Tell people ‘who we are’ rather than ‘who we are not’. Relatedly, in responding to any opposition, showcase who the community is, using the community’s own language and values — whether inclusion, diversity, or unity. Merely explaining who the community is not (e.g., “we are not a place of division or fear”) may actually strengthen associations between the community and the very actions and sentiments you are trying to avoid.

- Model empathy. Coalition leaders speaking out can model empathy for both the mosque community they are supporting and the broader community, even those speaking out against the mosque. Speakers can demonstrate that they hear and care about the community’s concerns while also explaining how those concerns will be addressed (see below).

- Offer a concrete path forward for addressing grievances. Provide clear channels and processes for addressing grievances or concerns. Throughout this, be specific. Outline exactly how to lodge complaints or concerns and how they will be addressed.

- Avoid inflammatory and dehumanizing language. Avoid language comparing people to animals or describing them as less than human (“dehumanizing language”), such as pests, deadly animals, disease, or filth, among others. Such dehumanizing labels prime people to think of and act toward others with less care or concern than they typically would other human beings. Further, words that refer to people and events in terms of war (“ambush,” “battle,” “crusade”), natural disaster (“they will flood the neighborhood”), and crime (“steal our neighborhood”) can subtly trigger fear, hostility, and anger in the public. This can also trigger a cycle of retaliatory language from the other group, only widening division and intergroup hostility.

- Use best practices for correcting misinformation. Correcting misinformation is tricky; it’s not uncommon to inadvertently amplify the very information we sought to debunk. To effectively correct misinformation, do so as quickly as possible and avoid repeating the misinformation itself. Instead, use positive framing to redirect the conversation. For instance, if there is a rumor spreading that a community mosque will increase crime, rather than stating that a mosque will not increase crime, reframe the message to address how mosques foster peace, community service, and interfaith cooperation. If it’s necessary to repeat the misinformation itself, provide a warning that the information is false before repeating it and ensure corrections are simple and easy to understand. Throughout this, ensure corrective messages come from credible and influential speakers among the target audience.

RECOMMENDATIONS

For mosque leadership:

- Educate community members and leadership about possible mosque opposition strategies and narratives and local community history

- Preempt anticipated legal obstacles such as by selecting a parcel of land that does not require rezoning for mosque use

- Assemble a strong team of experts from within and outside the Muslim community to undertake appropriate land acquisition and address any legal challenges

- Retain the best possible legal representatives that befit the nature of the opposition and local setting of the dispute in case of opposition

- Build strong neighborhood relationships with businesses, residents, and civic associations surrounding the mosque and establish trust and channels of communication

- Honor promises made to neighbors regarding land use, noise, and safety

- Develop and offer a concrete path for addressing future grievances

For interfaith and community allies:

- Build a coalition with community partners, including local businesses, houses of worship, and civic leaders to provide testimony in hearings and highlight the positive impact of diverse houses of worship

- Build a strong interfaith coalition to stand together for religious freedoms and fairness and demonstrate unity and mutual respect

- Avoid signaling negative norms and inflammatory or dehumanizing language to prevent misunderstandings about the prevalence of mosque opposition and mistreatment of opposition

- Prepare coalition members for rapid response via public messaging, speaking out in support, or meeting with opposition in case resistance to mosque arises

- Create a messaging plan by utilizing the most effective messengers and channels

- Use best practices to correct misinformation; be expedient, use positive framing, and avoid reinforcing stereotypes and giving false credence to opposition claims

For city council members and policy makers:

- Build relationships with local Muslim communities and leadership

- Establish direct channels of communication with local Muslims to collaborate and share information

- Reach out to local Muslim communities and leaders to understand issues and confront misinformation

- Understand the Islamophobia industry’s efforts to create fear of and resistance to mosques and Muslims

- Learn about anti-Muslim agenda disguised as anti-development arguments for mosque opposition

- Pursue factual information on the effects of diverse faith communities and the character and contribution of the local Muslim community

For media:

- Get educated on covering Muslims objectively

- Be aware of setting norms: avoid depicting opposition as more prevalent or widespread than it is. Instead, be sure to tell stories and include quotes from the local Muslim community and those working with them.

- Highlight the community’s self-declared positive values and identity rather than countering allegations made by opposition. Minimize negative associations made about the community. Remember that when you repeat/quote content that evokes stereotypes, dehumanization, etc., it creates increased familiarity and associations with them.

- Avoid inflammatory and dehumanizing language in reference to people so as not to trigger fear, hostility, anger, and retaliation that leads to greater inter-group divisions

- Use best practices for correcting misinformation and adopt positive framing to redirect conversation rather than repeating misinformation in an effort to debunk it

Analysis and Learning from Case Studies

In this section, this toolkit will highlight the nature, frequency, and history of anti-mosque activities in the U.S. and the ways in which they are intertwined with a broader context of anti-Muslim narratives and mobilization. To further understand these dynamics, this section provides an overview of findings from an analysis of the 42 instances of opposition to mosque construction or expansion compiled in a dataset by the ACLU for the years 2010 to 2018.

In addition, we analyze a 2016 book released by the Center for Security Policy titled Mosques in America: A Guide to Accountable Permit Hearings and Continuing Citizen Oversight, which aims to equip zoning planners and citizens with tools to “confront” mosque construction. The Center for Security Policy was founded by “renowned Islamophobe” Frank Gaffney Jr., and the book is authored by Karen Lugo, Esq., a constitutional law and religious land use specialist. As a known resource to delay or block mosque construction in the U.S., we reference the tactics recommended in this handbook with documented instances of mosque opposition.

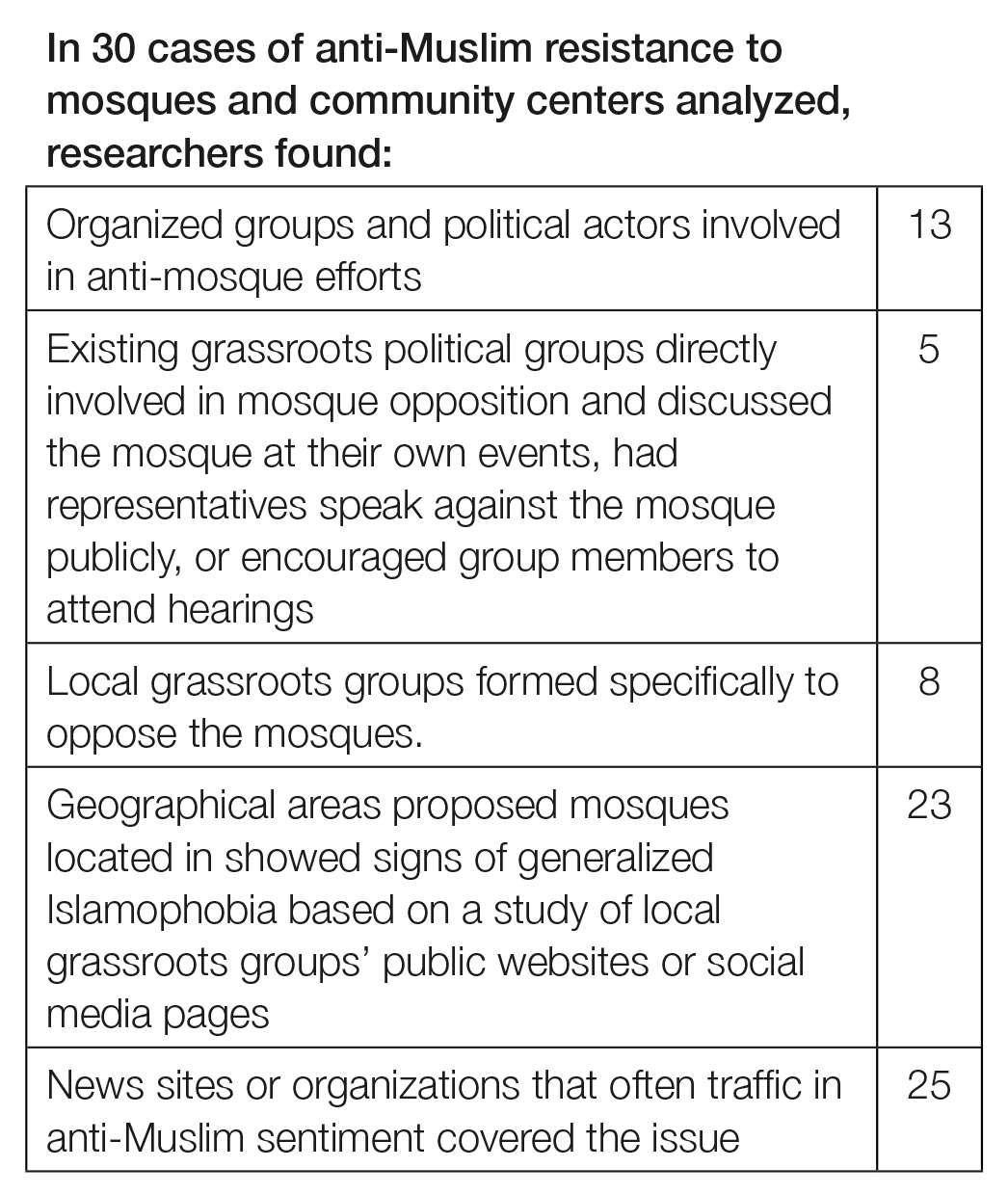

Of the 42 mosque opposition cases reviewed, the analysis found evidence of explicitly anti-Muslim sentiment in 30 cases. Below, we review an analysis of these 30 cases with a focus on (1) findings on timing, national and local narratives, and national and local organizing; (2) a breakdown of the most common narratives and frames mobilized for opposition (and, in some cases, used to counter the opposition); and (3) the opposition tactics used.

1. Findings on timing of opposition incidents

Timing of opposition incidents

Our analysis of the data indicates that national events and anti-Muslim rhetoric, in particular flashpoint events around political cycles and national mosque opposition, coincide with increased incidents of mosque opposition.

An analysis of the ACLU data indicates that mosque opposition activities occurred most frequently in 2010, coinciding with the midterm elections in the first Obama presidency and the highly publicized opposition to the Manhattan Park51 Islamic Center, and in 2016, coinciding the anti-Muslim and anti-refugee rhetoric and sentiment that animated the 2016 presidential election. These increases coincide with a broader uptick in anti-Muslim activities across the U.S. around election cycles.

This finding aligns with recent data indicating connections between anti-Muslim rhetoric and anti-mosque activity. Since 2012, anti-Muslim activity, including mosque attacks, anti-Muslim violence, public statements made by officials denigrating Muslims, legislative activity targeting Muslims, and opposition to mosques partially follows election cycles (McKenzie 2018 as quoted in Hussain and Saleh 2018). Further, researchers have found that hate crimes rise as a direct result of fear mongering and incendiary rhetoric.

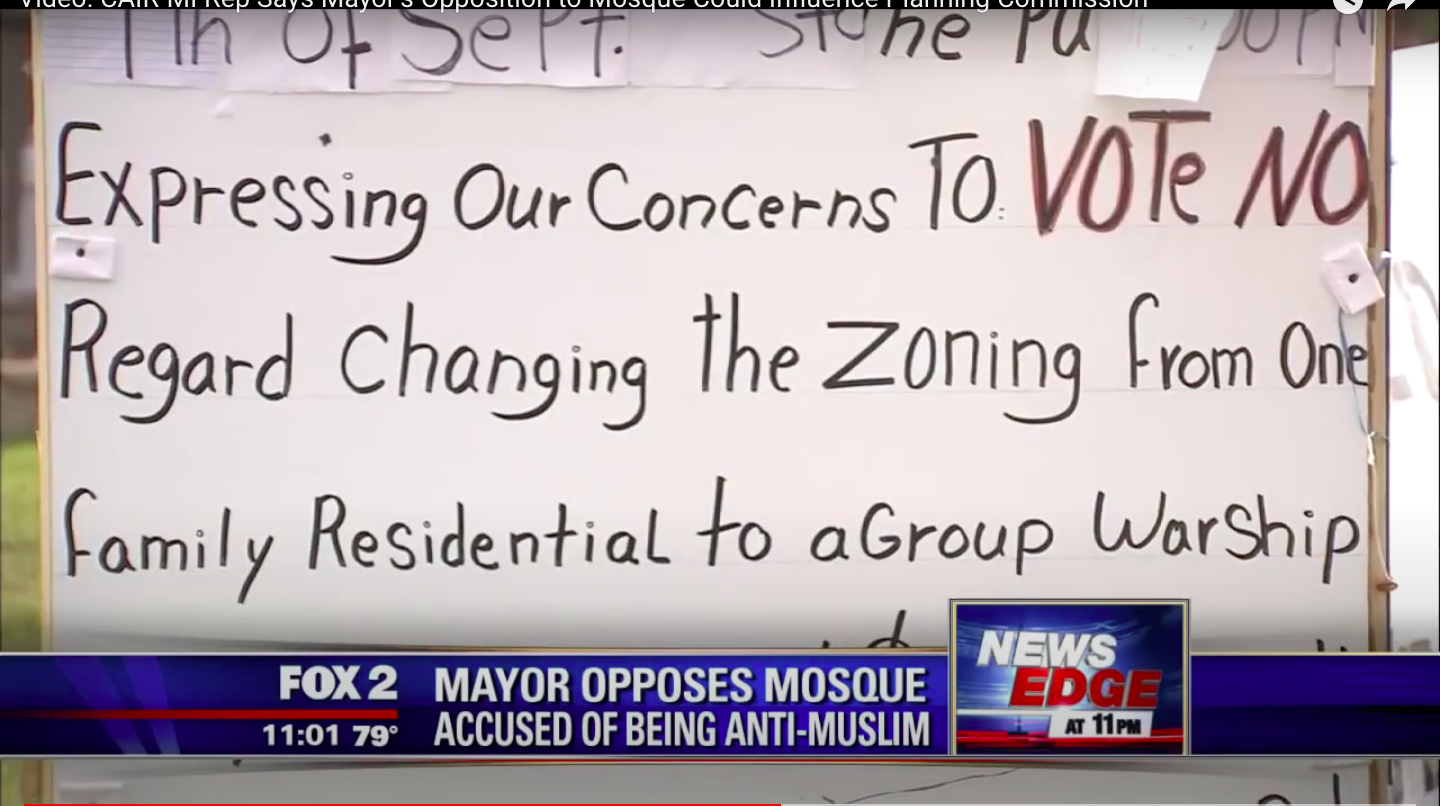

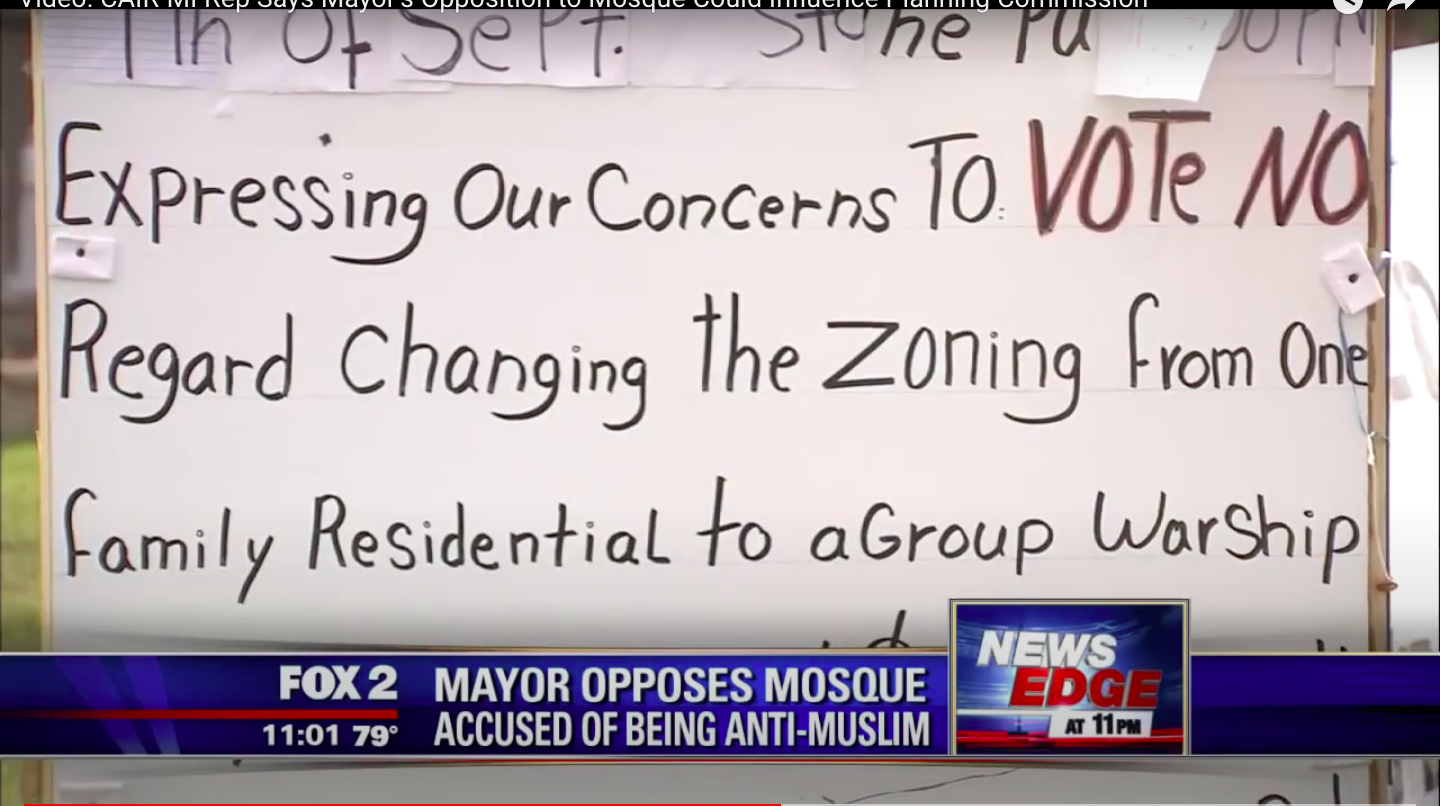

In nine of the 30 cases analyzed, researchers found that local public officials had expressed anti-Muslim sentiment with respect to or around the same time as the mosque case. While it cannot be established that public officials’ remarks spurred mosque opposition, this finding suggests that such rhetoric might deepen and perpetuate Islamophobia and, in turn, conflict over the construction or expansion of mosques.

2. Findings on the relationship between national and local narratives and organizing

In some of the cases analyzed, anti-Muslim opposition to mosques stemmed from only one or a few individuals. However, in highly publicized campaigns, anti-Muslim organizations have played key roles in Islamic center opposition efforts (Bail 2015). In 13 of the 30 cases with explicitly anti-Muslim expression analyzed for this toolkit, organized groups and political actors became involved in anti-mosque efforts. In five cases, existing grassroots political groups became directly involved in mosque opposition and discussed the mosque at their own events, had representatives speak against the mosque publicly, or encouraged group members to attend hearings. In another eight cases, local grassroots groups formed specifically to oppose the mosques.

In 23 of the 30 analyzed instances of explicit anti-Muslim resistance to mosques, the geographical areas showed signs of generalized Islamophobia based on a study of local grassroots groups’ public websites or social media pages. Records showed the areas had hosted events that likely included anti-Muslim sentiment, invited known Islamophobic speakers, or had active political groups that sometimes disseminated anti-Muslim content. In addition, 25 of the 30 cases were covered by news sites or organizations that often traffic in anti-Muslim sentiment though the role of such news coverage is unclear. This analysis likely yields a minimum count of organized anti-Muslim bias because the analysis only included public websites and pages and did not include local chat and websites.

Despite the nation-level media sources and political organizing that drives Islamophobic and anti-shariah sentiment, this analysis suggests that conflicts over mosques are largely local affairs. Opposition and proponents were represented by local actors, the organizations involved in the opposition were nearly always locally organized groups, and local municipal bodies were the primary vehicles for dispute resolution. Except in a few cases where local conflicts received considerable national attention such as in Manhattan and Tennessee, overt participation by national groups, if present, occurred in the later stages of the conflict after opposition had already mobilized locally.

The evidence of potent local mosque opposition efforts does not minimize the role of larger national and international anti-Muslim influences but rather demonstrates that where these influences are relevant, they have been operationalized and enacted through local political and cultural structures and involved the local individuals who make up their communities.

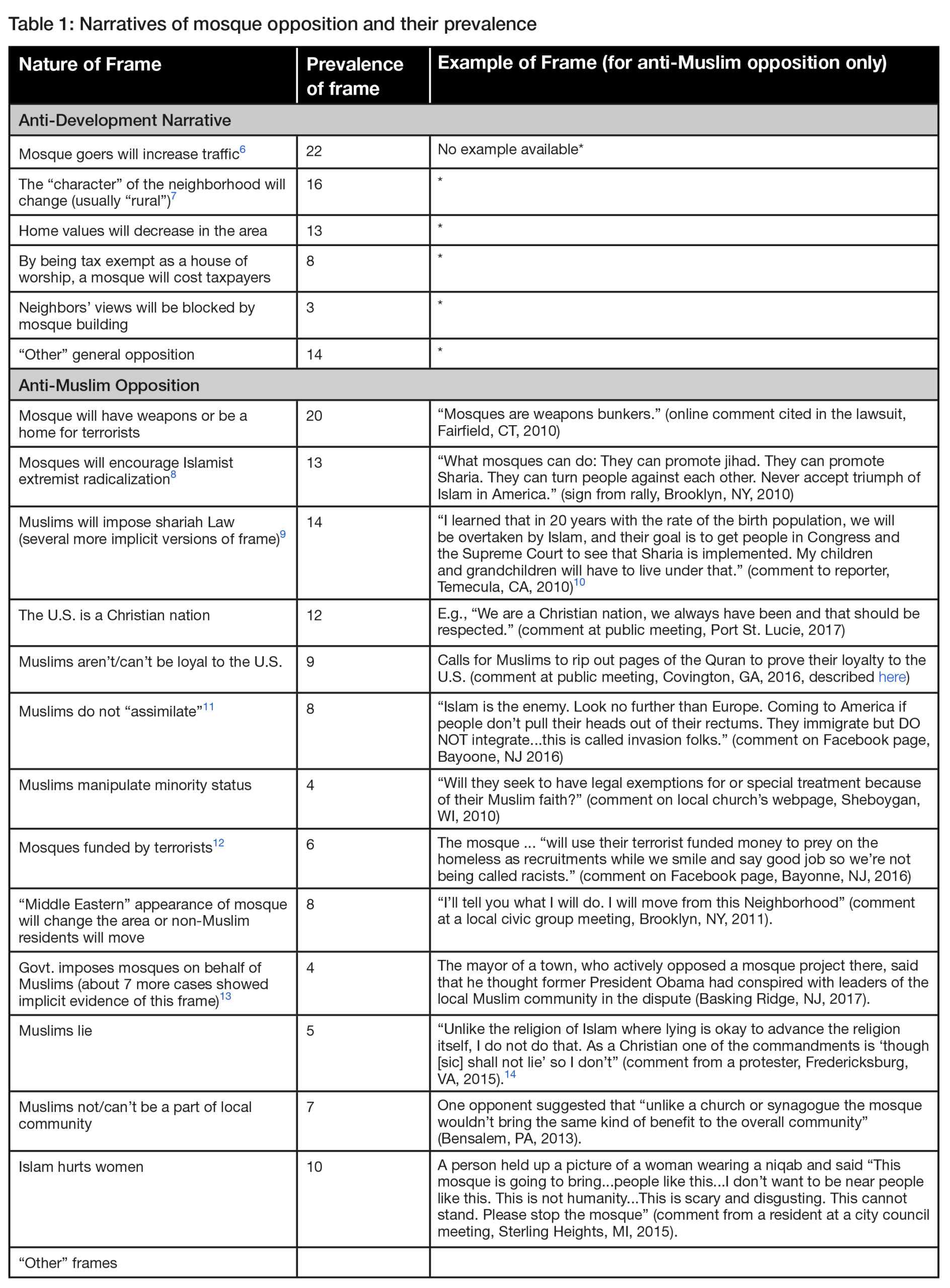

3. Analysis of narratives

Our analysis divides mosque opposition into two broad categories: (1) anti-development arguments, and (2) anti-Muslim arguments. These arguments unfold within a broader context of Islamophobic and anti-mosque rhetoric described above. Further, we examine organized Islamophobic efforts that purposefully delay and block mosque construction through legal means.

- Anti-Development Arguments entail resistance grounded in land use and zoning issues, traffic patterns, pedestrian safety, noise, and neighborhood concerns. As such, opposition framed in developmental terms is rooted in local laws (as opposed to the explicitly anti-Muslim opposition). This may involve organizations and groups coming together to prevent progress on a proposed mosque building. It is important to note that the Free Exercise Clause of the First Amendment protects citizens’ right to practice their religion and Federal Law Protections for Religious Liberty make it illegal to discriminate against individuals or groups on the basis of religion. Anti-development arguments may serve as the vehicle for anti-Muslim opposition.

- Explicitly Anti-Muslim Opposition: This entails opposition that is specifically couched in Islamophobic arguments, including that mosques will harbor terrorists, drive radicalization, or are un-American; related arguments depict Muslims as unable to assimilate to the U.S. Explicit anti-Muslim bias often manifests in confrontations outside of the legal system in the form of more grassroots efforts or can be inferred from organizational connections, printed materials, tone, and characteristic of opposition techniques employed. Anti-Muslim sentiment does sometimes show up in public and legal confrontations, such as comments at public zoning board meetings.

As noted earlier, this analysis of 42 cases found evidence of explicit anti-Muslim sentiment in 30 instances. Importantly, anti-Muslim sentiment may be repackaged as land use concerns to render mosque opposition more palatable. ‘Legal’ [anti-development] opposition may mask implicit anti-Muslim bias which is difficult to parse through until exposed or expressed. Foley (2010) found that while anti-Muslim sentiment has sometimes infused popular opposition to mosque and Islamic center construction, such opposition is also animated by general concerns over local development. However, with evidence of anti-Muslim actors intentionally using and recommending non-anti-Muslim framing when mounting opposition to mosque construction to conceal true Islamophobic intent and increase chances of success in the courts, anti-development arguments should be examined more critically.

Indeed, our analysis shows a combination of explicitly anti-Muslim with general opposition frames, suggesting some support for the argument anti-Muslim sentiment has been incorporated into more typical “NIMBY” [Not In My Backyard] or anti-development sentiment.

Within each type of opposition narrative — anti-development and explicitly anti-Muslim opposition, we broke down the narratives of opposition into specific frames that were used across the 30 cases. The table below outlines these frames (the 16 most prominent anti-Muslim frames and their frequency and the six most common anti-development frames) and shows the frequency of each type of narratives across the 30 analyzed instances. Note that some comments and examples of opposition narrative frames touched upon several narratives. Individual comments that reflected more than one frame were counted as many times as was applicable.

Understanding the Strategy: Excerpt from Mosques in America:

In its foreword, Mosques in America by Karen Lugo is describes itself as “a how-to manual for patriotic Americans who are ready to counter the leading edge of Islamic supremacism: its infrastructure-building through the construction of shariah-promoting mosques that serve to alienate and radicalize.”3

Giving further credence to the purposeful muddying of anti-development narratives as well as how to sidestep allegations of discrimination, Lugo states that “While concerns over separatism and radicalization animate much of the focus on new mosque construction, these issues are not within the purview of local officials. These are very important cultural concerns and this manual will explain how they may be addressed in general at city hall and specifically in other community forums.”4

Among recommended actions that are rooted in Islamophobia but packaged as anti-development or procedural opposition, Lugo suggests that volunteer committees be “assigned to investigate all aspects of the regulatory process. These include: reviewing the zoning codes; researching and comparing prior approvals for similar treatment of other applicants; anticipating representations of event descriptions and activity levels; assessing safety concerns and impact issues; previewing comments to be presented at public hearings; and preparing statements for other venues on radicalization countermeasures and assimilation concerns.”5 (emphasis added) We also highlight oppositional narratives found in these instances that have been recommended by the Center for Security Policy in the Mosques in America handbook.

Across these frames, one common theme was the idea that the conflict was really a question of what “the community” needed or wanted rather than a constitutional issue — whether civil rights or private property. For example, one comment on an article in a local paper about the conflict argued that when the complaints of residents who opposed the mosque were dismissed, they were “disenfranchised” (Alpharetta, GA, 2010).

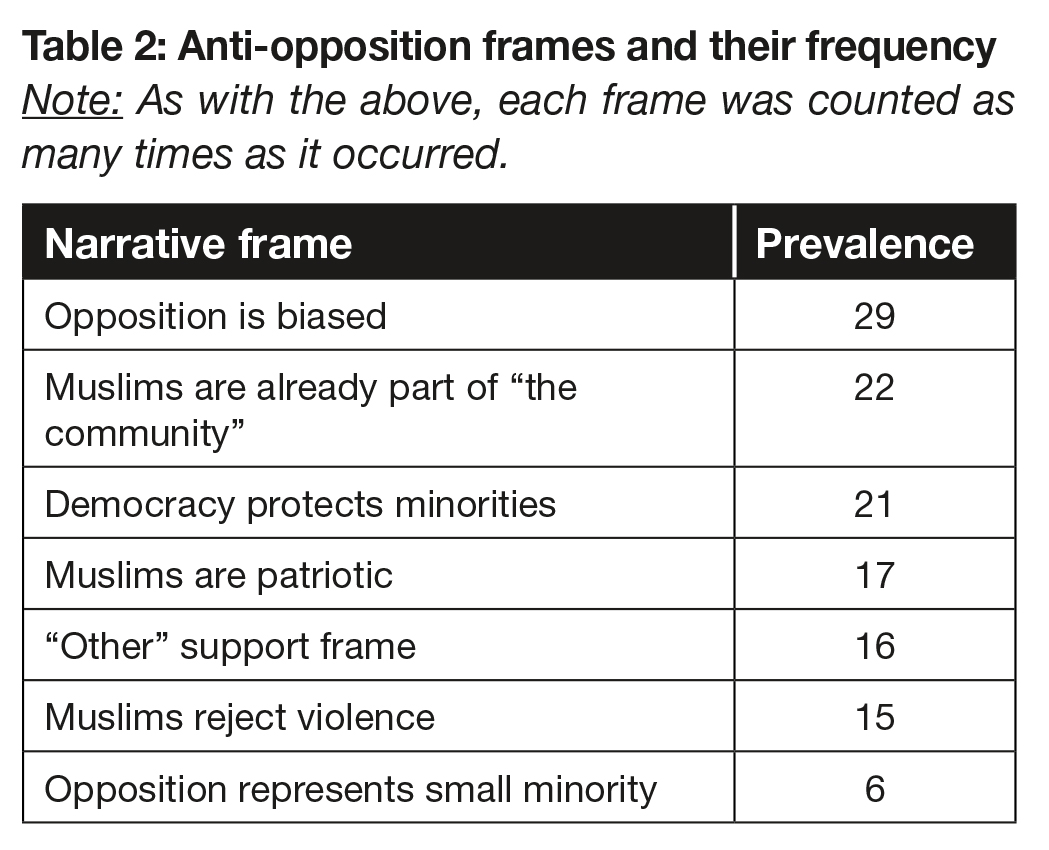

In several of the cases analyzed, there were clear narrative frames used by anti-opposition groups that sought to combat mosque opposition. Supportive arguments used to defend mosque-building were made by parties proposing mosque construction as well as allies. These positive narrative frames and their prevalence were as follows.

Note: As with the above, each frame was counted as many times as it occurred.

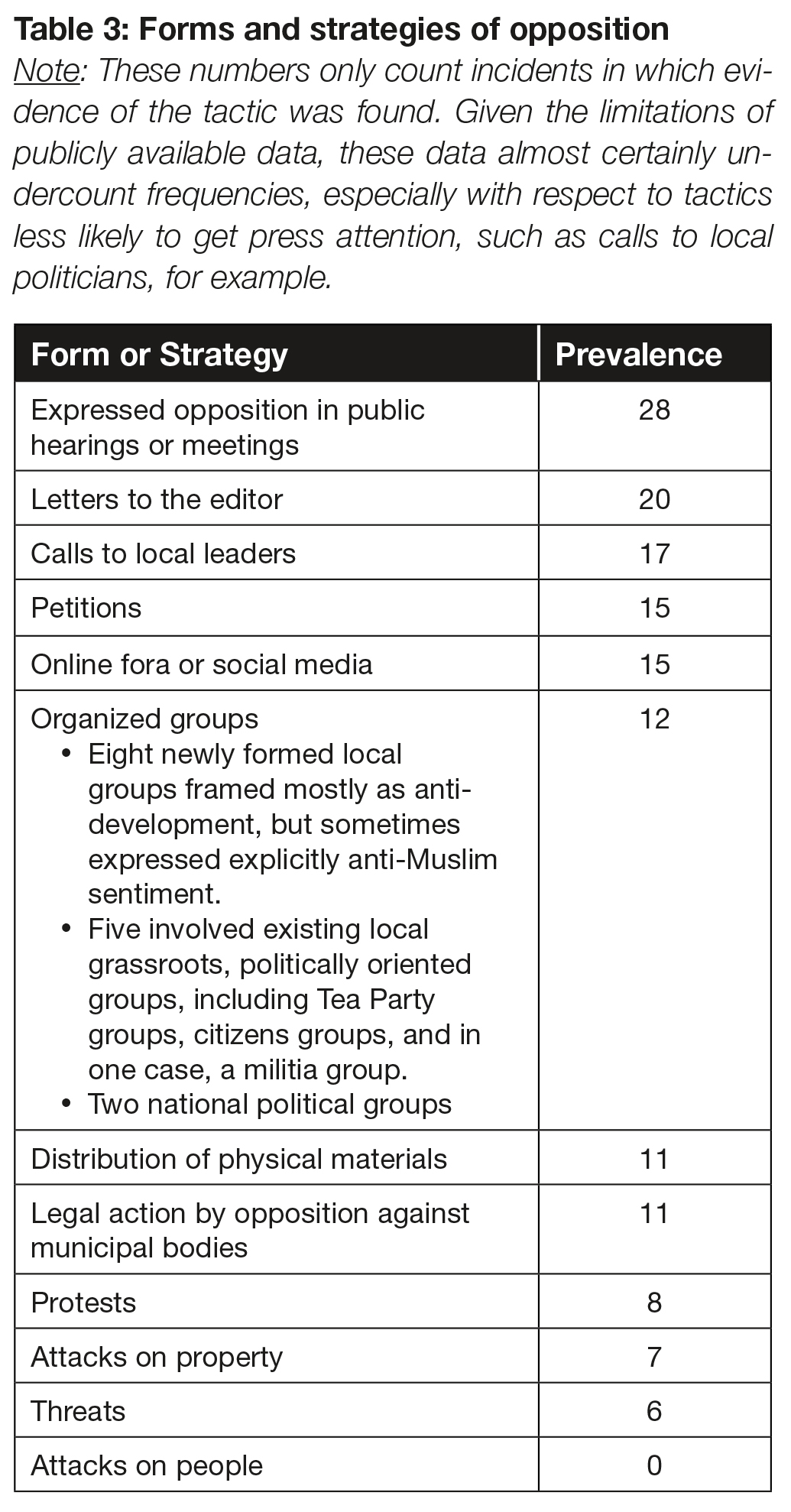

4. Analysis of Tactics: What Does Mosque Opposition Look Like? Forms and Strategies of Opposition Expression From 30 Cases

The below table highlights the different tactics used within this broader context to oppose construction and expansion of mosques and Islamic centers by looking at the different tactics and their frequency across the 30 cases of explicitly anti-Muslim cases analyzed.

Table 3: Forms and Strategies of Opposition

Note: These numbers only count incidents in which evidence of the tactic was found. Given the limitations of publicly available data, these data almost certainly undercount frequencies, especially with respect to tactics less likely to get press attention, such as calls to local politicians, for example.

In-Depth Case Studies

Rayyan Center, Plymouth Township MI: Best Practices in Action

Context: Plymouth Township in Wayne County, Michigan, had an estimated population of 27,000 in 2010. Part of the Detroit Metro area, Plymouth Township is about 27 miles away from the city of Dearborn in Michigan, home of one of the largest Muslim populations in the U.S. While affording easy access to cultural and social needs, Muslim worshipers in Plymouth Township found themselves commuting 20 to 30 minutes to attend prayers at the nearest mosque in a nearby town. In 2016, the Plymouth Township Muslim community decided to take steps to overcome the hardship of a long drive and build a mosque closer to their community. Thus, the idea of Rayyan Center was born.

Challenge: According to the founders of Rayyan Center, prior to 2016, the group worshiped at a small mosque called Meadowbrook Islamic Center in neighboring Northville Township. The mosque occupied a single-family home in a residential area. As the parking needs of Meadowbrook Islamic Center grew, the group petitioned the city to rezone the parcel to create additional parking. However, the rezoning petition became contentious after a local anti-Muslim activist spearheaded opposition efforts. While the opposition included some valid traffic-related concerns, the overarching resistance was Islamophobic in nature. The anti-Muslim activist drummed up local resistance to the construction of a mosque in their vicinity, arguing that they “don’t want Dearborn here.” Ultimately, the opposition campaign effectively halted the rezoning process, and the Muslim group sold that property.

With this recent experience in mind, the founders of Rayyan Center sought to purchase a parcel of land in an industrial area to minimize opposition from neighbors. After the land acquisition, community members petitioned for a land variance for the construction of a house of worship. Soon after the rezoning meeting was announced by the Board of Zoning Adjustment, the public became aware of plans to build a mosque in the area. A member of the Plymouth Township Muslim community heard callers complain about the proposed mosque in a local call-in radio show. A board member found “Stop the Mosque” flyers circulating in the area of the proposed mosque. The flier cited increased traffic and noise concerns around five daily prayers.

Actions:

- The Board set up consultations with community members to best address land use change issues and opposition concerns. Primed for opposition to their mosque proposal based on events in their neighboring community, the Rayyan Center Board moved quickly to prepare for all possible arguments as soon as resistance to Rayyan Center became evident.

- Rayyan Center opted to run a positive campaign to highlight the potential positive impact of a mosque in the proposed location. Some community members suggested taking an aggressive stance by retaining high-profile legal counsel, invoking First Amendment Rights and Federal Religious Land Use protections to litigate and fight for mosque construction. However, after soliciting input and deliberations, Rayyan Center board members decided to adopt a moderate and non-confrontational approach. The leaders took steps to address traffic and noise concerns as a backup plan.

- The Board partnered with a well-respected mid-sized firm and a local lawyer who was connected in the Township and familiar with the local context. The Board aimed to keep a low profile to create conciliatory and collegial conditions for the zoning hearing and considered several law firms of various sizes.

- The community activated their interfaith, Muslim leadership, and business-owner networks to create a strong supportive narrative to counter opposition. Rayyan Center community and faith leaders invited their interfaith allies and friends to stand with them and vouch for the benefits of a variety of houses of worship. Large employers and business owners in favor of ease of worship for their workers and the ability to attract a more diverse workforce joined the group of mosque supporters to offer their testimony. Other Muslim leaders and community members from across the Detroit Metro Area lent support to Rayyan Center.

Results:

-

- The rezoning hearing for Rayyan Center was the most well-attended public meeting in Plymouth Township history. Supporters of Rayyan Center attended in large numbers whereas the opposition consisted of a small minority.

- Rayyan Center’s rezoning petition was approved swiftly without controversy or ill will.

Case Study: McLean Islamic Center, Virginia

Context: In 2015, members of the Muslim community of McLean, Virginia, purchased the site of the disused Berea Church of Christ, first established in 1959, with a view to construct the new McLean Islamic Center (MIC). The proposed mosque would be the only Islamic center in a 10-mile radius. In the decades following the establishment of the original church, the area had seen major growth. The site is now in close proximity to the upscale shopping mall Tyson’s Corner in Fairfax County, Virginia, and the surroundings have been developed into wealthy residential neighborhoods. Across from the proposed site of the MIC, a Tyson’s Sheraton hotel, a 24-hour Walmart SuperCenter, an elevated Metro and rail station, a car dealership, and a 24-hour gym were already operating. Half a mile away from the site were three churches, one of which, McLean Bible Church, is a ‘mega church.’ The neighborhood of Carrington abuts the site of MIC on three sides and has an active and well-funded homeowners’ association (HOA) made up of several influential individuals who are deeply invested in the progress of their area.

Early developments: The Carrington HOA took keen interest in all potential buyers of the church parcel and learned of the purchase of the church by a group of local Muslims through personal contacts. MIC board members, too, were aware of the historical interest and influence of the Carrington HOA in local development projects and their interest in the conversion of the church property into residential lots. Through research, the MIC board discovered that the Carrington HOA privately disapproved of the land deal. Preemptively, the MIC board set up meet and greets with all surrounding neighbors early on in the process of the purchase to establish good relationships and assuage any fears. While meetings with other nearby neighborhoods went smoothly, at the meeting with Carrington residents, members of the Carrington HOA casually mentioned their intention to legally oppose the construction of a mosque in their neighborhood.

Early Restrictions on MIC: Soon after the purchase of the land parcel and before MIC began operations at their new site, the Carrington HOA vocalized concerns about traffic and noise pollution to the Board of Zoning Appeals (BZA) in 2015. Though the BZA approved MIC to begin use of the land as a house of worship, it was with strict limitations on operations. While other stipulations pertained to zoning, usage, and construction technicalities, there were stringent regulations on operations. The three key restrictions were as follows:

- The dawn prayer, fajr, would be capped at 10 worshipers despite the building’s 52 parking spots.

- Daily operations would conclude at 10:30 p.m., limiting congregations, extended Ramadan prayers, and any overnight community activities. There would be no prayer service between the hours of 4 to 7 p.m. during weekdays, which impacted MIC’s ability to offer afternoon and evening prayers.

- Restrictions were placed on residential street parking and a parking monitoring program was mandated.

MIC board members agreed to these conditions to start operations in some capacity and kept in view their limited membership at the time of inception. In 2016, MIC formally began operations and opened its doors to worshipers. A parking management plan was set in place, with ample signage to indicate parking rules. Police officers were hired for traffic management for Friday afternoon prayers. MIC complied with timing restrictions and remained mindful of noise activity. MIC also began work on pre-approved parking lot expansion in accordance with Fairfax County road expansions.

Neighbor Relations: As a gesture of neighborliness, MIC prepared for and hosted quarterly meetings with the neighbors to review conditions and operations that continue to this day. However, from the outset, MIC community members faced hostility from Carrington residents. In particular, MIC activities were subjected to surveillance by neighbors who set up lawn chairs, cameras, and other apparatus to observe traffic, count the number of congregants at the pre-dawn prayers, and monitor noise from MIC. In 2018, an anonymous complaint about more than 10 vehicles in the mosque parking lot was made to Fairfax County. Logistically, MIC was unable to impose a 10-person restriction on morning prayers for a 200-member congregation as there is no way to confirm or predict how many worshipers will attend Fajr prayer service. As a result, in 2018, MIC suspended morning prayers altogether to comply with the condition.

Challenge: After the filing of the anonymous complaint in 2018, and the subsequent suspension of pre-dawn prayers, MIC submitted a special permit amendment to the BZA to extend MIC’s hours of operation and remove attendance limitations for MIC as the MIC had met previous development conditions and had seen a proportionate growth in the size of the congregation. However, this amendment request was met with stiff resistance from the Carrington HOA over several contentious public hearings.

In officially registered complaints, neighbors expressed concern about decrease in their home values, increase in traffic, safety concerns, and elevated noise levels from mosque activities as the main reasons for their resistance to the construction of the MIC in their area. To bolster their arguments against MIC, the HOA conducted traffic and noise studies of larger Islamic centers in the DMV area and retained high-profile lawyers to mount a strong legal opposition.

Specifically, the HOA expressed concerns about increased traffic load for Friday prayers, during Ramadan, and on the days of Eid when the Muslim community observes the two largest celebrations in the Islamic calendar. New pedestrian safety measures, changes to existing turn lanes, and the expansion of the existing parking lot on the parcel were also opposed. The HOA also claimed that surface noise from cars driving to the mosque and the sounds from shutting car doors and locks at the times of the Islamic prayers at dawn and after sunset would be higher than the 85 decibels stipulated under the local Noise Ordinance that extended from 10 p.m. to 7 a.m. and disturb neighbors.

Informally and via in-person interactions during city meetings, HOA members revealed Islamophobia that simmered under the legal surface. HOA members commented that the MIC building would draw “Middle Eastern looking” people to the area and they did not want their neighborhood to “look like that,” among other similar remarks.

Actions:

- To best prepare to counter the opposition, MIC assembled a team of experts from within the Muslim community, including legal experts, structural engineers, water mitigation experts, and zoning law experts to study all aspects of the building and its uses.

- MIC retained the best-suited legal teams they could afford and worked with the firms of Reed Smith and King and Spaulding over the course of the litigation process.

- MIC conducted independent traffic and noise studies to provide objective insight into opposition claims of elevated noise and pedestrian endangerment.

- MIC leadership reached out to their interfaith allies for support and public testimony.

- MIC community members and leadership arranged to connect with their future neighbors and sought to establish cordial relations by organizing meet and greet events.

- MIC leadership took stringent measures to ensure that the MIC community honored promises made to their neighbors and the county to continue operations.

Results:

-

- Over a series of BZA meetings, the MIC community refuted all opposition claims, including noise and traffic-related concerns on the basis of evidence.

- MIC’s existing interfaith relationships and outreach efforts resulted in an outpouring of support from interfaith allies who stood up for MIC’s right to operate freely.

- In 2017, MIC opened its doors for worship for all five Islamic prayers.

- MIC created and continues to implement a strict parking plan to avoid disturbing neighbors in Carrington.

.

Conclusion

This toolkit provided an overview of arguments deployed against mosque construction and effective strategies for countering this opposition. This research is based on a survey of 42 instances of mosque opposition in the United States, two case studies, prior research and guidance by ISPU, and best practices for resisting division, hate, and violence. As resistance to mosques will likely be grounded in local experiences, values, and conflicts, it’s critical that any strategies for response are similarly tailored to local dynamics.

Research Team

Dr. Elizabeth A. Yates

Report Co-author, Researcher, and Analyst

Azka Mahmood

Report Co-author

Rachel Brown

Report Contributor; Founder and Executive Director of Over Zero

Laura Livingston

Report Contributor; Regional Director, Europe at Over Zero

Megan Kelly

Report Researcher and Analyst

Dalia Mogahed

Report Advisor; Director of Research, ISPU

Erum Ikramullah

Research Project Manager, ISPU

Communications Team

Katherine Coplen

Director of Communications, ISPU

Rebecka Green

Creative Communications and Media Specialist, ISPU

Infographic

This downloadable infographic offers recommendations and resources to understand, preempt, and challenge opposition to mosque and Islamic center construction and expansion.

Endnotes

- We focused on these specific years and this specific dataset. There were additional cases in this dataset prior to 2010 (15 cases listed between 2006 and 2009). Further, the dataset is not exhaustive as there were cases identified by our researchers that were not included in the dataset.

- Note that a similar case study by the Pew Research Center spanning the years 2009 to 2012 had found 53 occurrences of mosque opposition.

- From the Foreword, K. Lugo (2016), Mosques in America, pg 1.

- K. Lugo, (2016), Mosques in America, pg 12.

- K. Lugo, (2016) Mosques in America, pg 19.

- In pages 22-33 in Mosques in America, Karen Lugo uses Al-Farooq Youth and Family Center in Minnesota as a case study to describe detailed traffic, parking, and land use patterns and concerns for communities to highlight when mosque construction is proposed.

- In chapters four and five over pages 61-67 in Mosques in America, Karen Lugo cautions against applications for variance use under zoning laws and “smart growth” city planning that allow for the situation of mosques within residential areas and cities. “It is very important to know enough about the law to be able to recognize when planning departments are preparing to give so many allowances to an applicant that the very structure of the zoned area is at risk.” Pg. 62

- Mosques in America, pg. 16: “The Muslim demographic that causes consternation is based in the twenty percent that responded to a Pew survey in 2013 by saying that Muslims should remain “distinct” from American society. This indicates resistance to integration and is reflective of those likely loyal to tribal custom, Islamic law, or Koranic doctrine rather than willing participation in secular civil society.

- In Chapter 20: “Free Speech: Use It or Lose It” in Mosques in America, Karen Lugo undertakes a lengthy discussion on the freedom of speech and equates Muslims’ constitutional right to the adherence to shariah with a weakening of the American constitution. For instance, she writes that “Islamist groups like CAIR [Council on American Islamic Relations] often come to city hall on a mission to shape policy according to Islamic Sharia speech codes.” Pg. 160.

- This quote was found in press clips and not directly from the dataset.

- Mosques in America, Page 15: “the numbers of “home grown” and immigrant Muslims that hold anti-constitutional views on such issues as freedom of conscience, women’s rights, and free speech are very troubling. When Sharia-adherent mosques are central to Muslim life and culture, there are important concerns for American neighborhoods. As mosque-based life is communal to the degree that pious Muslims may be at the Islamic center most days of the week — sometimes for many hours in a day — and the lifestyle is cloistered to the point that participation is exclusive to Muslims, it is easy to see that integration trends will be heavily influenced by what is being taught in the mosque. Europe’s example of separate and distinct cultures is a very troubling object lesson for Americans.”

- In Chapter 18: Anticipating Enforcement: When Government Fails to Uphold the Law, Lugo links mosques with terrorist groups. Pg. 133-136.

- Also in Chapter 18, Lugo accuses law enforcement and political managers of being biased in favor of Muslims and mosques. Pg. 133.

- The man who made this quote was using a sign that referenced a hate group (League of the South).

Additional Sources

Bail, Christopher. 2015. Terrified: How Anti-Muslim Fringe Organizations Became Mainstream. Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press.

https://www.cnn.com/2016/11/14/us/fbi-hate-crime-report-muslims/

https://www.ispu.org/building-mosques-in-america-strategies-for-securing-municipal-approvals/

http://ldsnet.fairfaxcounty.gov/ldsnet/ldsdwf/4636498.PDF

https://www.census.gov/quickfacts/fact/table/plymouthchartertownshipwaynecountymichigan/BZA115218

Citations for the section “Messaging Considerations”:

Paluck, E., L. (2009). What’s in a Norm? Sources and Processes of Norm Change. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology 96(3) 594-600. https://doi.org/10.1037/a0014688

Tankard, Margaret E., and Elizabeth Levy Paluck. “Norm Perception as a Vehicle for Social Change.” Social Issues and Policy Review 10, no. 1 (2016) 181-211. https://doi.org/10.1111/sipr.12022

Martin, Steve. “98% Of HBR Readers Love This Article.” Harvard Business Review, November 24, 2014. https://hbr.org/2012/10/98-of-hbr-readers-love-this-article

Belavadi, S. and Hogg, M.A. (2019), “Social Categorization and Identity Processes in Uncertainty Management: The Role of Intragroup Communication,” Advances in Group Processes (Advances in Group Processes, Vol. 36), Emerald Publishing Limited, Bingley, pp. 61-77. https://doi.org/10.1108/S0882-614520190000036006

Maynard, J. L., & Benesch, S. (2016). Dangerous Speech and Dangerous Ideology: An Integrated Model Dangerous Speech and Dangerous Ideology: An Integrated Model for Monitoring and Prevention. Genocide Studies and Prevention: An International Journal, 9(3), 70-95. http://dx.doi.org/10.5038/1911-9933.9.3.1317

Hanne, M., & Hawken, S. J. (2007). Metaphors for Illness in Contemporary Media.

Medical Humanities, 33, 93-99. https://doi.org/10.1136/jmh.2006.000253

Nyhan, B., & Reifler, J. (2012). Misinformation and Fact-checking: Research Findings from Social Science. New America Foundation, Retrieved from https://www.issuelab.org/resources/15316/15316.pdf