.

Illinois Muslims

Needs, Assets, and Opportunities

JULY 28, 2022 | BY DALIA MOGAHED, DR. JOSEPH HOERETH, OJUS KHANOLKAR, AND UMAIR TARBHAI

Results: Individual

Survey questions pertaining to the individual included a broad range of topics: identity, health, food access, volunteering, and faith-based giving. Our analysis focused on identifying assets and needs, which we discuss below.

ASSET: Strong Faith Identity

DOWNLOADS

TABLE OF CONTENTS:

Page 1: Executive Summary, Report Overview

Page 2: Introduction, Results: Demographics

Page 3: Results: Individual

Page 4: Results: Family, Results: Community

Page 5: Results: Broader Society, Recommendations and Opportunities

DOWNLOADS

TABLE OF CONTENTS:

Page 1: Executive Summary, Report Overview

Page 2: Introduction, Results: Demographics

Page 3: Results: Individual

Page 4: Results: Family, Results: Community

Page 5: Results: Broader Society, Recommendations and Opportunities

Results: Individual

Survey questions pertaining to the individual included a broad range of topics: identity, health, food access, volunteering, and faith-based giving. Our analysis focused on identifying assets and needs, which we discuss below.

ASSET: Strong Faith Identity

Muslim respondents in our study identified strongly with their faith. Around 84% of Muslim respondents stated their faith was very important to their self-perception, compared with 39% of the Illinois general public respondents. Previous research shows that a stronger faith identity among Muslims is linked with a stronger national identity. In fact, in a study from 2016, 91% of Muslims who stated they had a strong faith identity also had a strong American identity, while only 68% with a weak faith identity identified strongly with being American [7]. Previous research has also suggested that faith can act as a protective factor against negative mental health outcomes.

While faith was a strong identifying factor, focus group participants were quite varied with regard to how they talked about their identities. Some describe multiple national identities, including American, a country of origin if they were immigrants as well as an ethnicity in combination with the other two identities. Notions of what it means to be American were complex as well. For example, the identity of what some might describe as the proud immigrant was discussed, where one might say living in America and being American is a privilege with specific rights and responsibilities. Yet, another view on identity heard in the focus groups was a bit mixed. It is that of a Muslim who is American but believes that being a Muslim in America requires one to acknowledge America’s history of injustice and present-day inequities while also committing to confronting those inequities.

“For me being American is having the rights and freedoms of each and every American that makes us feel we are Americans, if we have rights and freedom just like everyone else.” – Muslim resident of Illinois, 24

In a focus group with African American participants, the sense was that faith is inextricably a part of their self-identity to such an extent that questions about their race separate from their faith do not align with how they see themselves. Being Muslim is a part of being Black for them and vice versa.

“When we make a conscious decision to follow the tenets of Islam, we become formally Muslim. But beyond the African American tradition, we are Muslim by nature.” – African American respondent, 72, Chicago South Side

NEED: More Halal Options

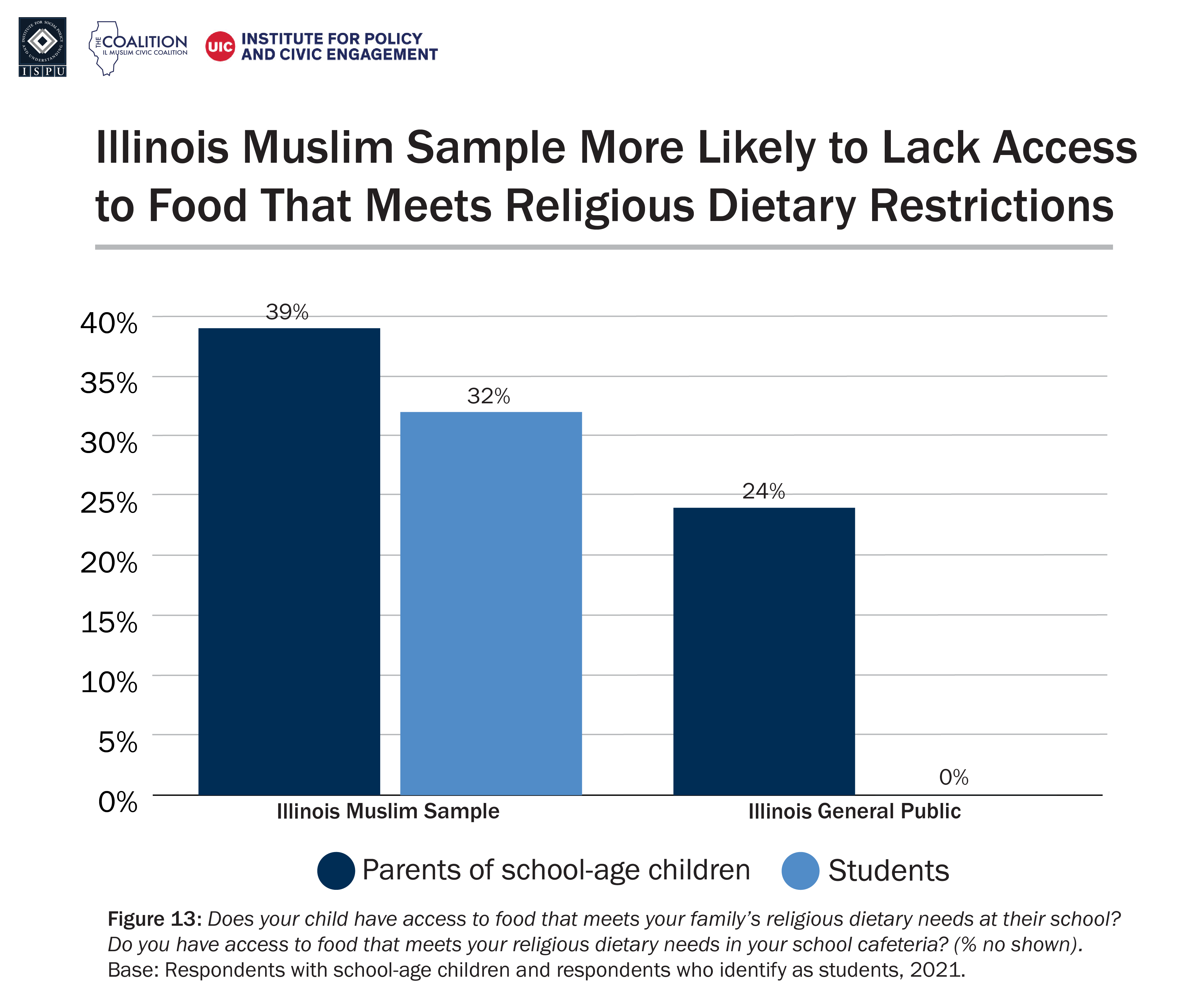

With this finding, however, it should be noted that there also need to be systems in place to support their faith needs. Specifically, 94% of Muslims stated it is ‘somewhat’ or ‘very’ important that their purchase decisions be halal (74% stated it was very important, and 20% stated it was somewhat important). Yet, 39% of Muslim respondents with school-age children and 32% of students enrolled in college said they didn’t have access to halal food at their school. In contrast, around 48% of respondents in the Illinois general public sample stated their faith was an important factor in their purchase decisions. One quarter of Illinois general public respondents with school-age children (24%) and none of the college students reported not having access to food that met their religious dietary restrictions at their school. This is, of course, not surprising as the majority of the general public do not have religious dietary restrictions.

Focus group participants reinforced the importance of observing halal or at least trying to eat halal. Some indicated they or someone in their network may drive great distances to access halal food. However, they note that it is becoming increasingly more accessible.

“We drive to Peoria, St. Louis, Champaign, Chicago to get halal. Now, the big stores carry halal meat. …Walmart has halal meat. Meijer is also starting to carry halal meat. [I’m] buying up the lamb they had and I’ve started seeing the halal mark on it. We are starting to see more international things in grocery stores because we have a big population.” – African American respondent, 57, Springfield, Illinois

NEED: Access to Appropriate Healthcare

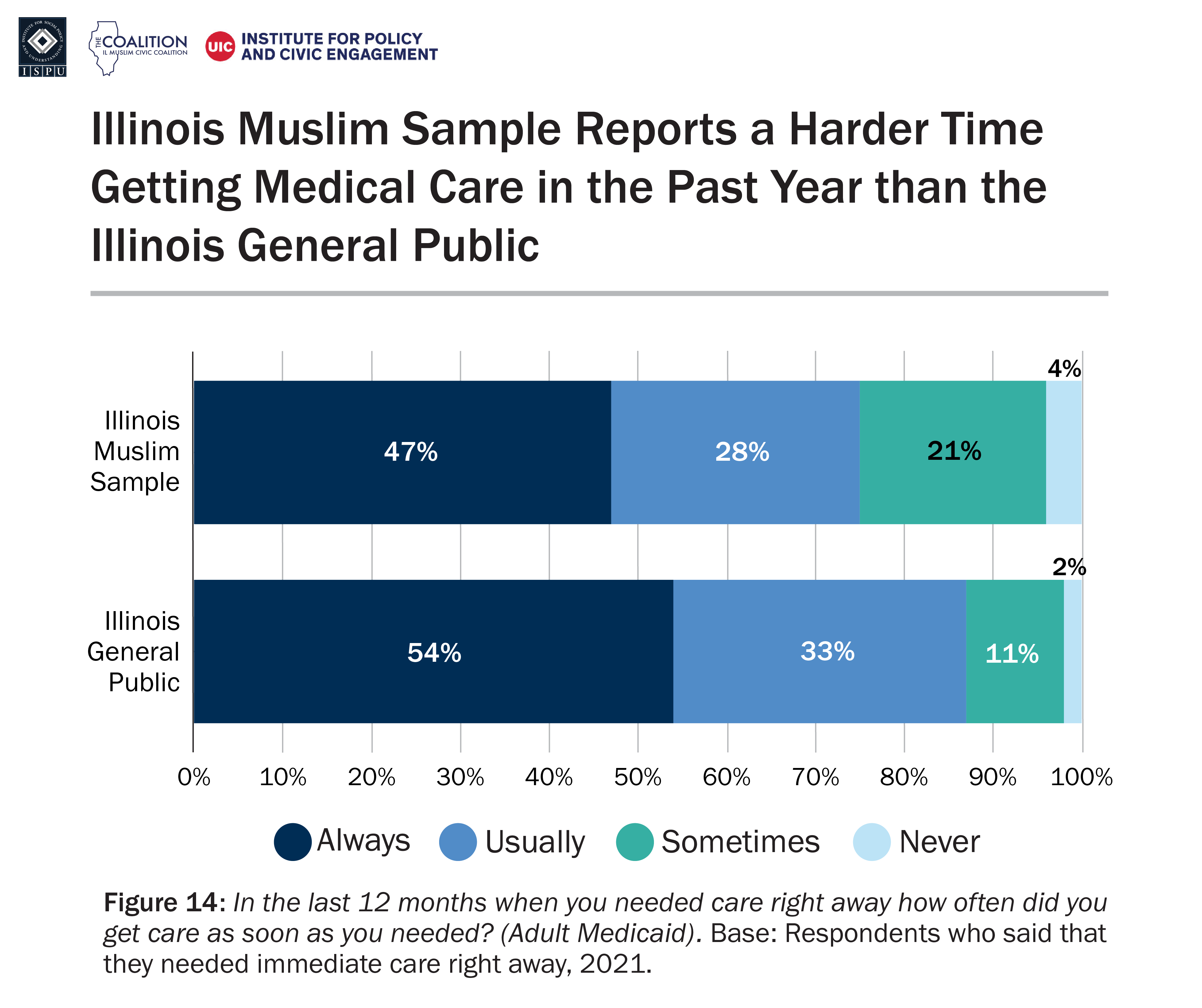

While Muslim respondents reported needing immediate care less often than did those in the state’s general public when they did need care, Muslims in our survey had a harder time getting it. One-fifth (21%) of Muslim respondents said they needed immediate care in the last 12 months, but 25% of those who needed care stated they ‘sometimes ‘or ‘never’ got care as soon as they needed it. In comparison, around 30% of the Illinois general public sample stated they needed immediate medical care right away in the past 12 months, and around 13% of those individuals stated they ‘sometimes’ or ‘never’ got care as soon as they needed it. That means Muslims in our sample who needed care right away were twice as likely as the general public to sometimes or never get it (25% vs. 13%, respectively).

Future research is needed to assess what factors explain this result, and how much, if at all, implicit bias may play a role in Muslims’ greater likelihood to report difficulty receiving timely healthcare. According to ISPU’s 2020 national survey of American Muslims, roughly a third of Muslims who reported experiencing religious discrimination said it occurred while seeking healthcare.

NEED: Affordable, Culturally Appropriate Mental Health Services

The need for support extends to mental health. In the year prior to the survey, half of survey respondents, both Muslim and the general public, experienced some sort of mental illness symptom (47% and 51%, respectively). These symptoms included anxiety, sadness, and loss of joy. While the pandemic and its stressful effect on so many individuals may explain some of this, it is a longer term challenge, as 53% of the Muslim sample and 56% of the Illinois general public sample reported they had experienced mental health symptoms at some point in their life. Most respondents who reported experiencing mental illness symptoms at some point in their life also reported experiencing them in the past year.

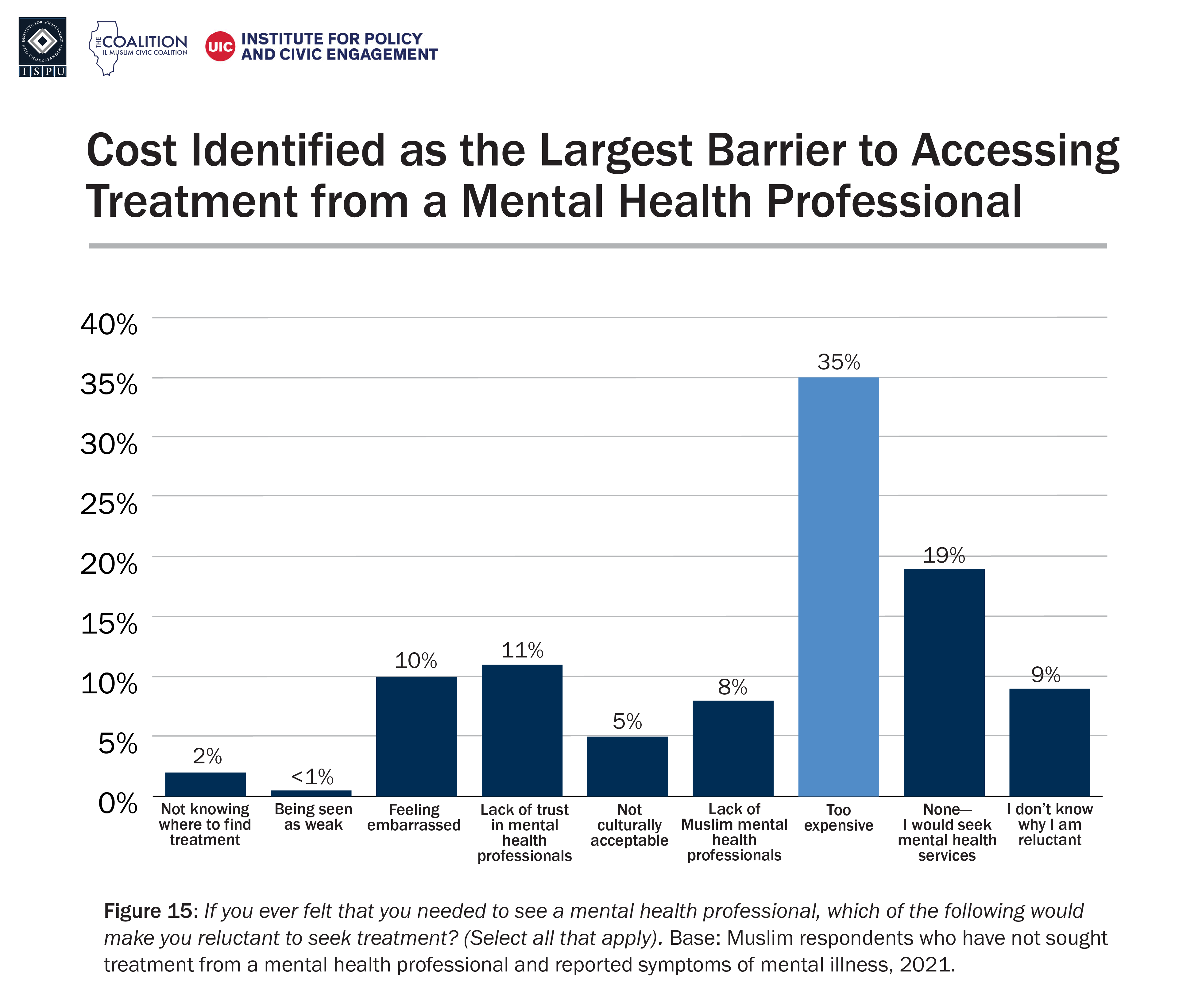

However, despite similar rates of reported negative mental health symptoms, Muslim respondents are less likely than their Illinois general public counterparts to seek treatment. Thirteen percent of the Muslim sample sought help from a licensed therapist in the year prior to the survey, as opposed to 24% of the Illinois general public. When asked about reasons for reluctance in seeking treatment, among respondents in the Illinois Muslim sample who reported symptoms of mental illness but did not seek treatment, 35% reported that it would be too expensive, 11% said they didn’t trust mental health professionals, and 10% said they would feel embarrassed. This finding indicates that more affordable mental health services are a significant need within the Muslim population.

The survey also asked respondents if they have ever attempted to take their own life. Among the Muslim sample, 8% reported attempting suicide. While lower than the 18% of individuals in the Illinois general public sample who report the same, any number is too high, and these findings reiterate the significant need for culturally appropriate and affordable mental health services for the Illinois Muslim community.

In exploring these findings further, focus group participants identified mental health support as a critical need within the community, specifically indicating they feel that such services need to be more accessible. Participants also consistently mentioned a very strong stigma, although not always using the word “stigma,” identifying a negative association or perception of mental health within the community. Some participants indicated that mental health issues are sometimes perceived as a result of individual behavior or failure to do something, as if the individual is being blamed for causing the mental health condition. This notion of “self-blame” or “blaming the victim” sentiment discourages individuals from seeking help when they need it, regardless of whether that help comes from within the community. The main point of their comments was that efforts should be made within the Illinois Muslim community to reduce or address this stigma.

“I think the public, we are not good at dealing with mental health. The only hope is within ourselves. You can share with a friend and that person can help you in cases of stigma. A friend you can talk to personally. I need a friend who is a Muslim like me who can understand and get whatever I’m talking to him or her about.” – African American Illinois resident, age 24

“It may just be my own impression, but mental health isn’t something talked about. If anyone has it they are told to do what needs to be done but don’t dare talk about it or share your experiences. It’s a mix of both peer pressure and clearly stated. People have said ‘if that’s something you’re dealing with, you can go talk to someone, but you don’t have to say that to bring everyone else down.’” – Illinois resident of South Asian origin, age 20