Measuring the Legal and Media Responses to Ideologically Motivated Violence in the United States

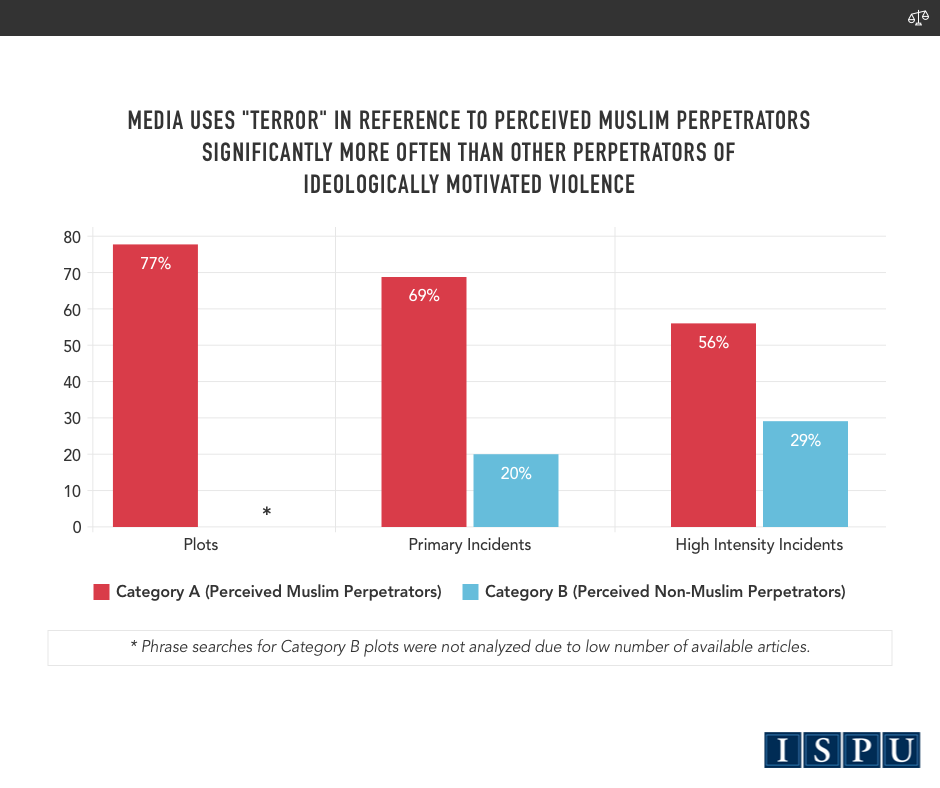

Hate crime or terrorism? Lone wolf or extremist? These words are often used to describe ideologically motivated violence in the U.S., and their use by officers of the law and members of the media has impact on real cases.

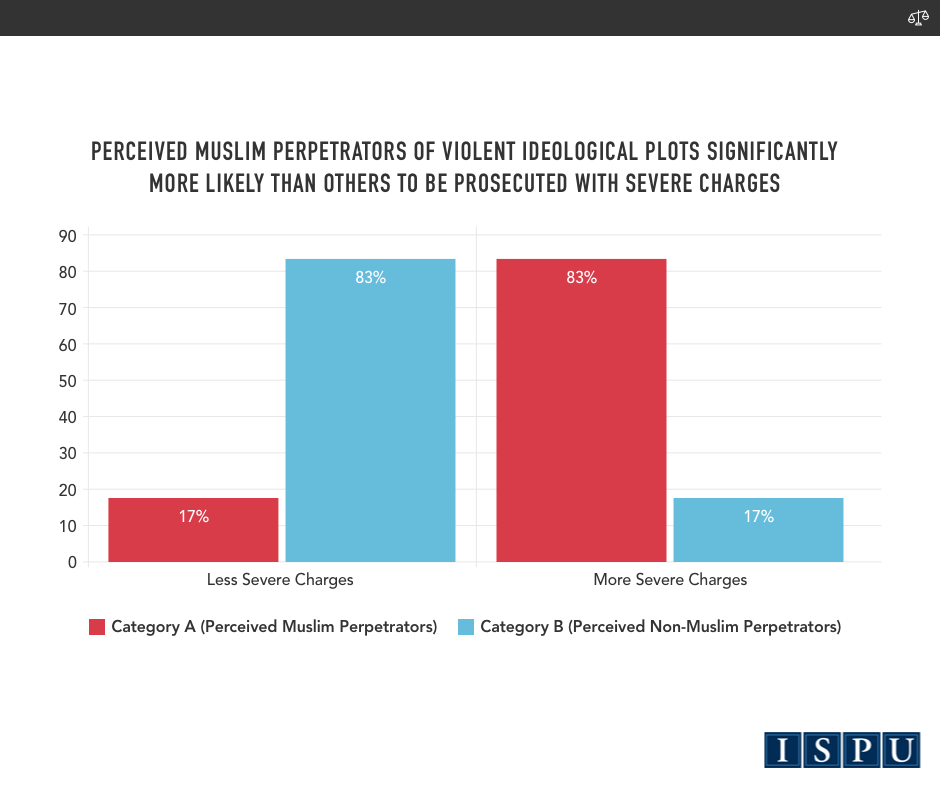

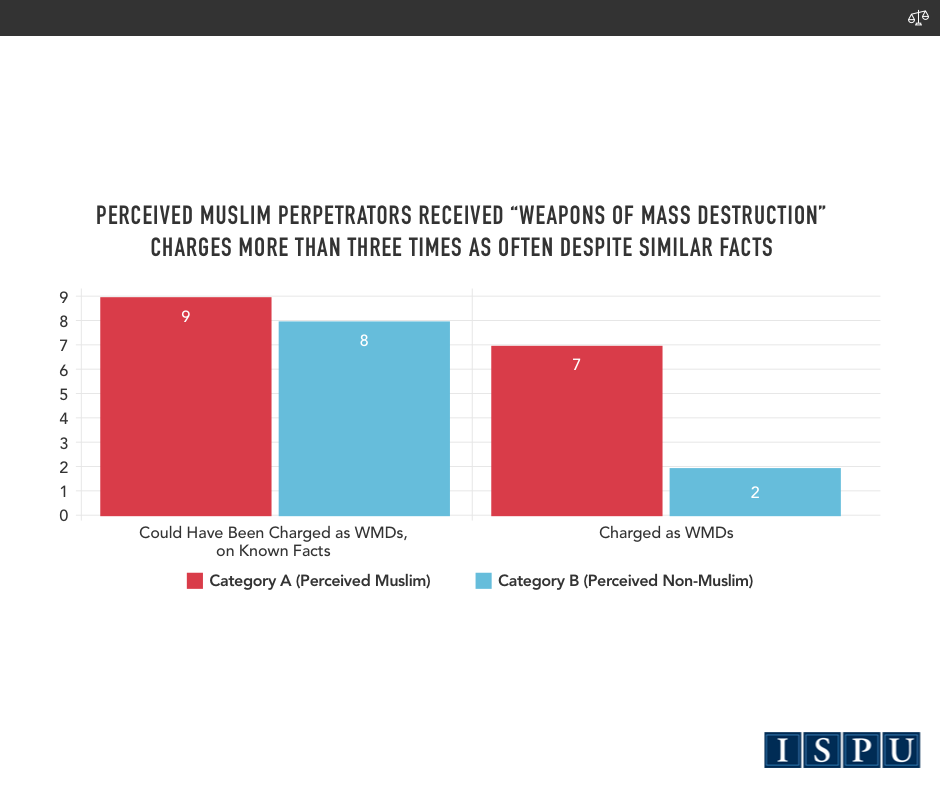

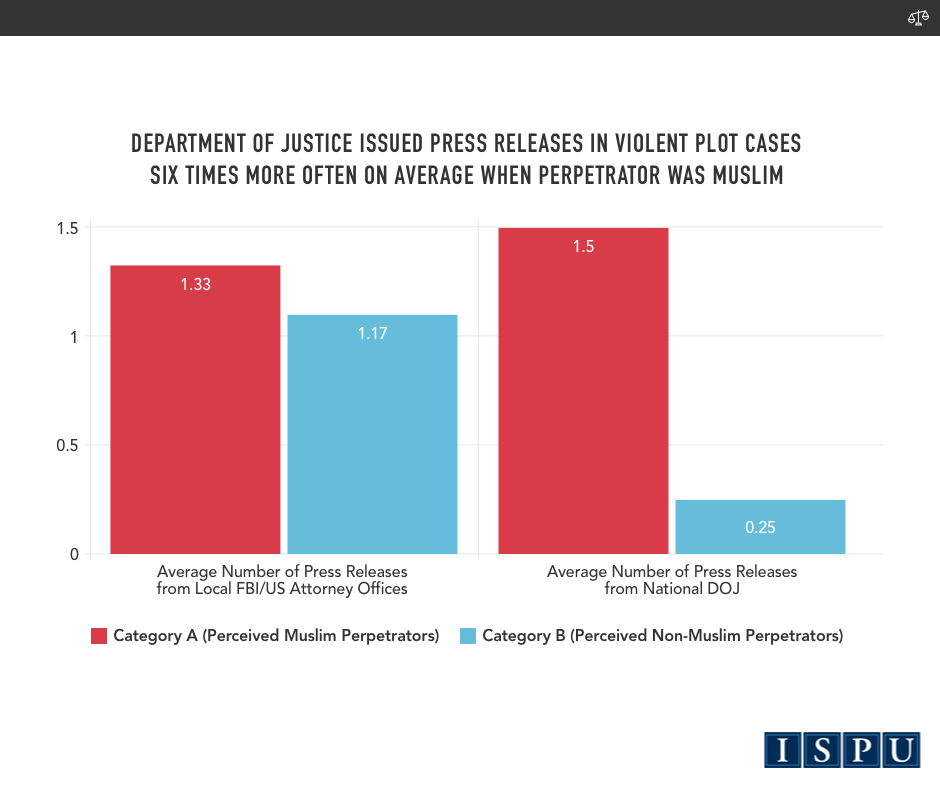

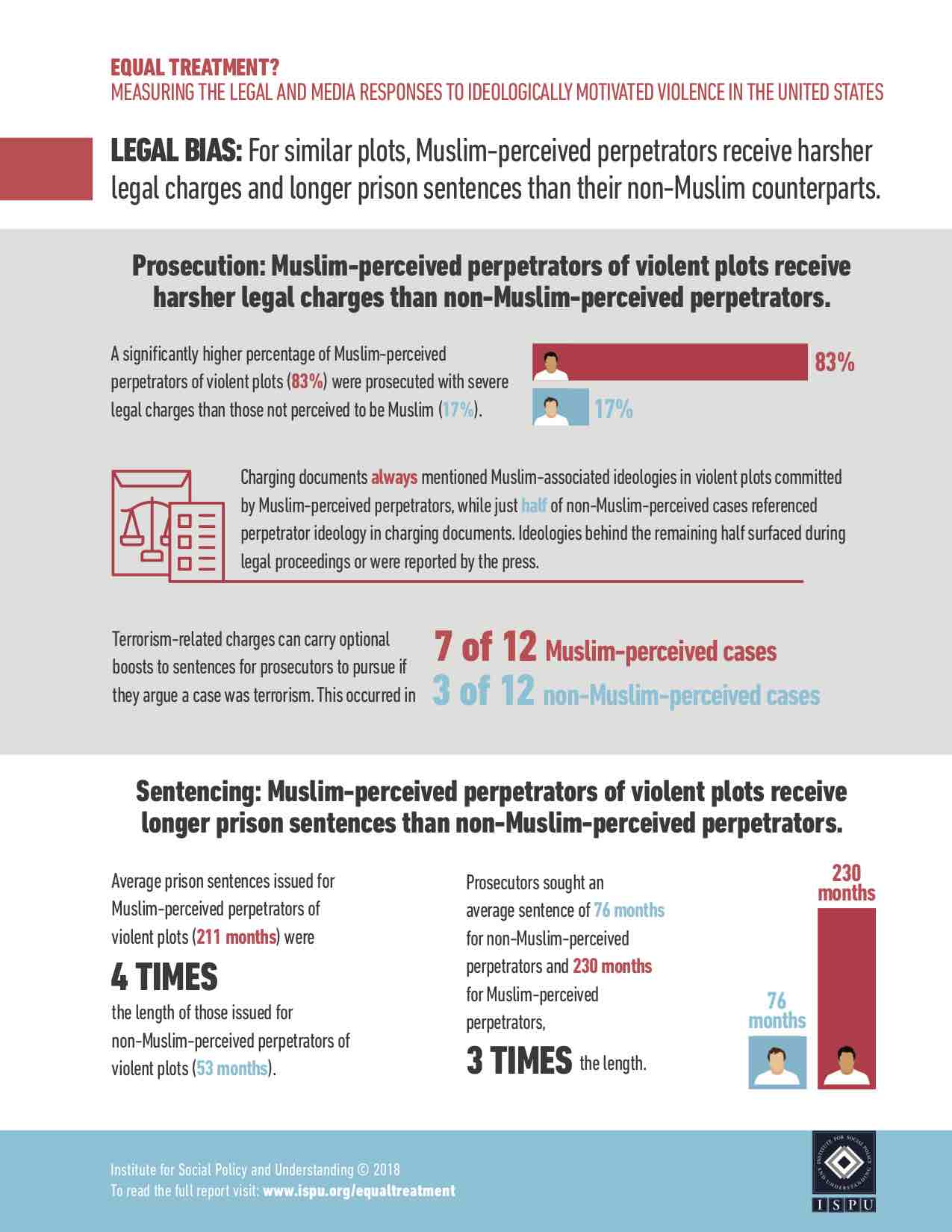

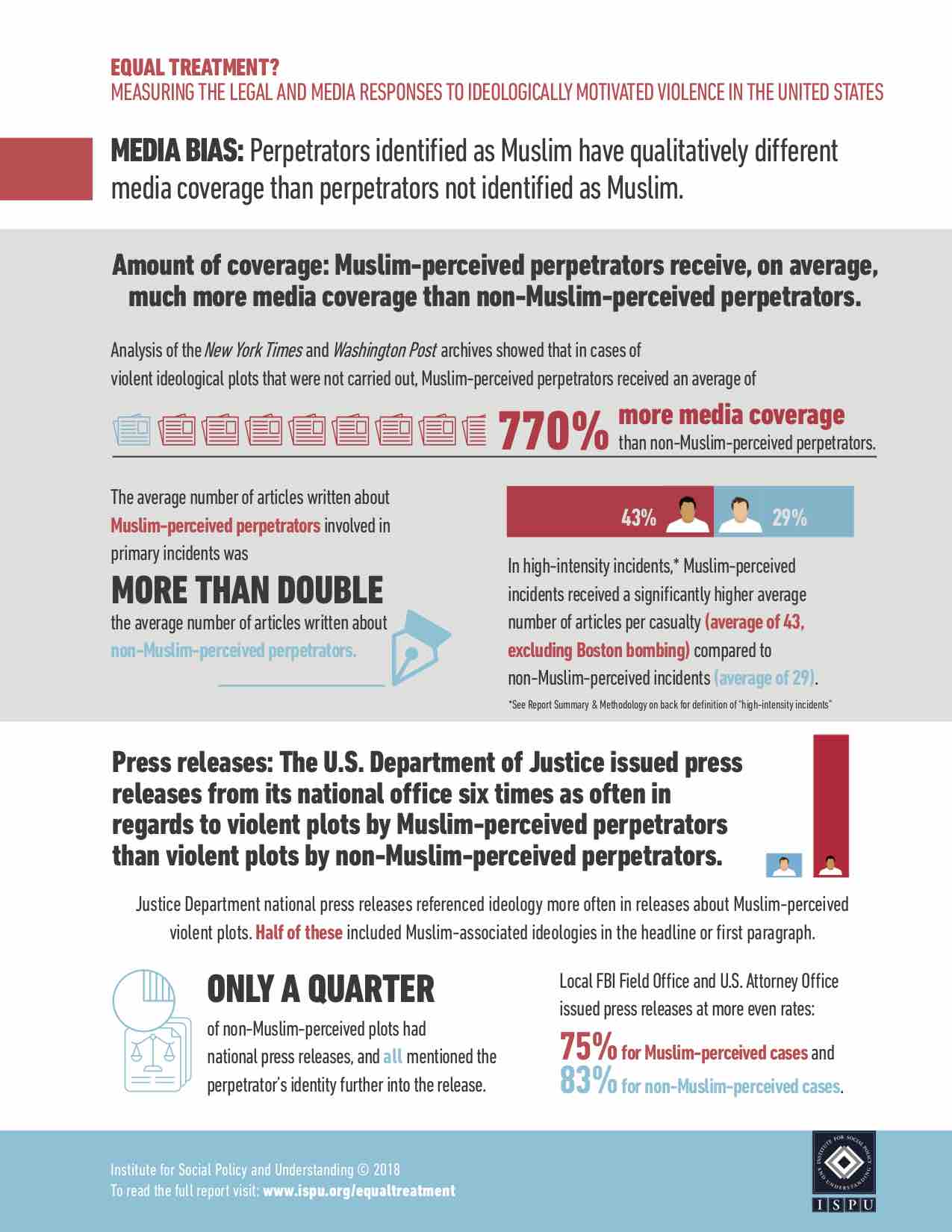

Equal Treatment?: Measuring the Legal and Media Responses to Ideologically Motivated Violence in the United States examines cases in which perpetrators of similar crimes receive dramatically different legal and media responses. This empirical analysis compares media coverage, law enforcement tactics, charges, and eventual sentencing when the perpetrator of an act of ideologically motivated violence is perceived to be Muslim and acting in the name of Islam vs. not perceived to be Muslim and motivated by another ideology, such as white supremacy.

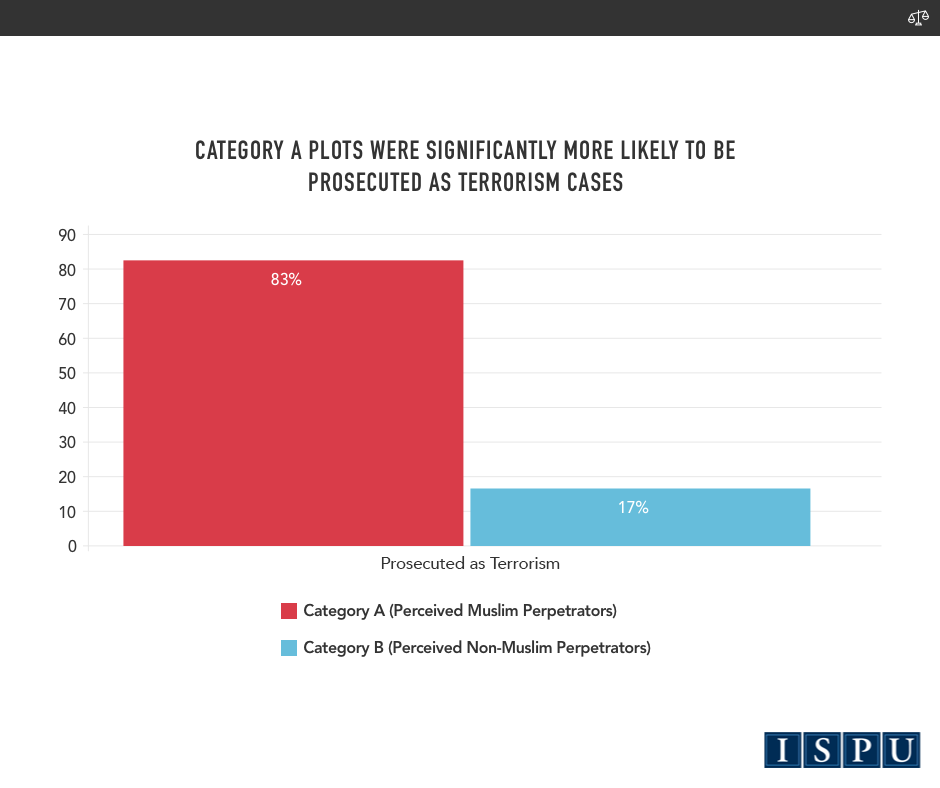

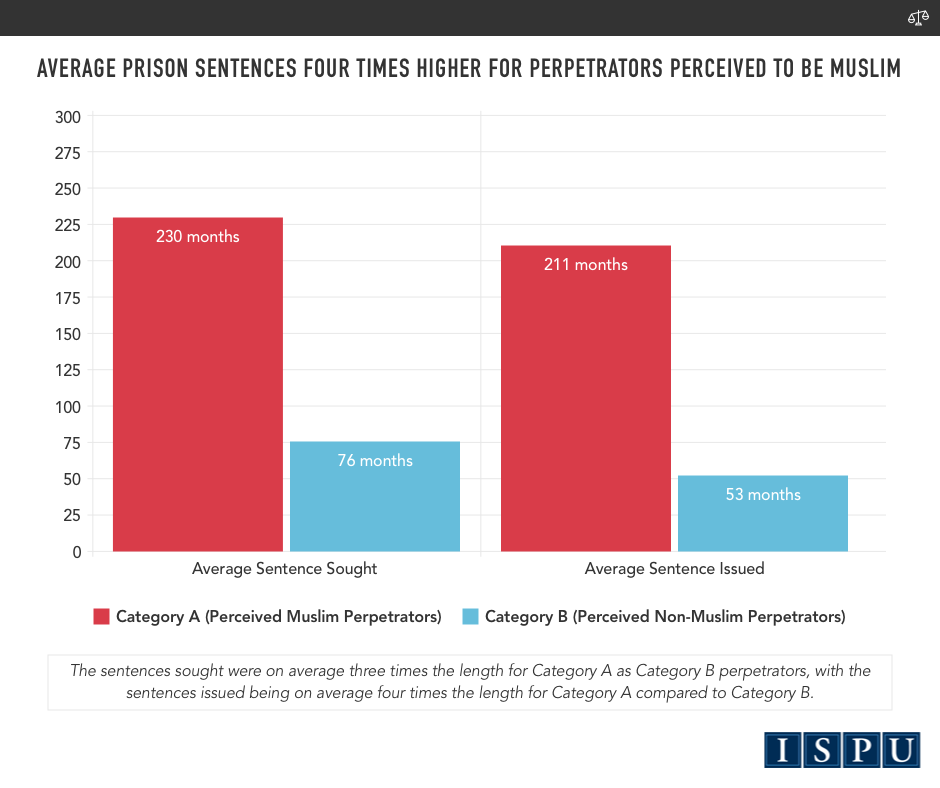

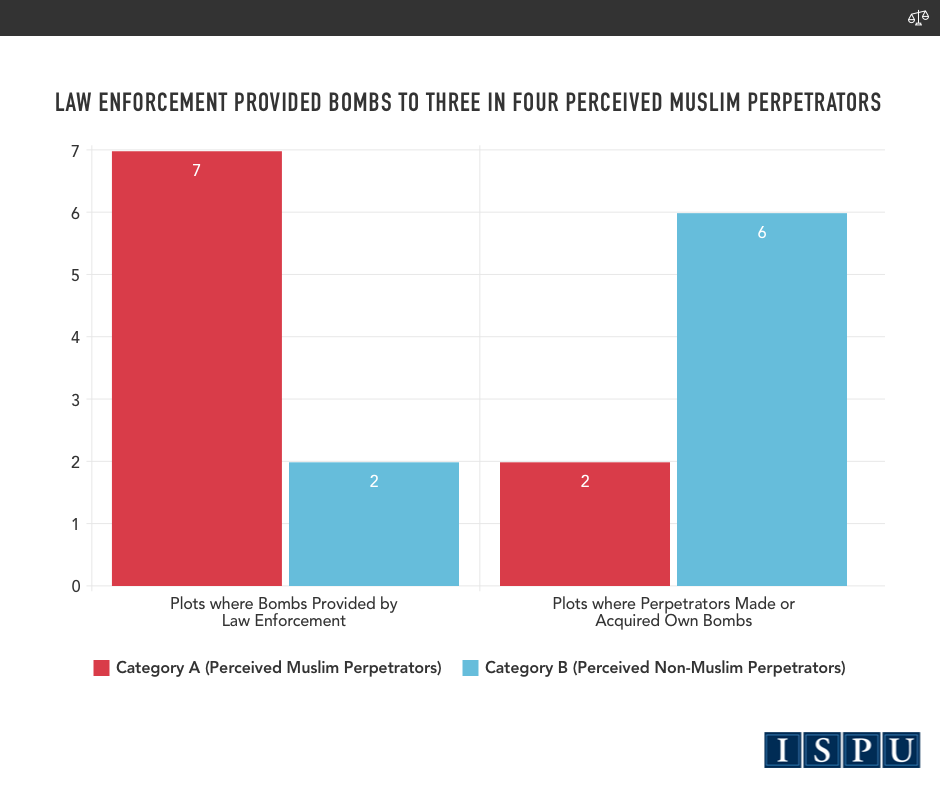

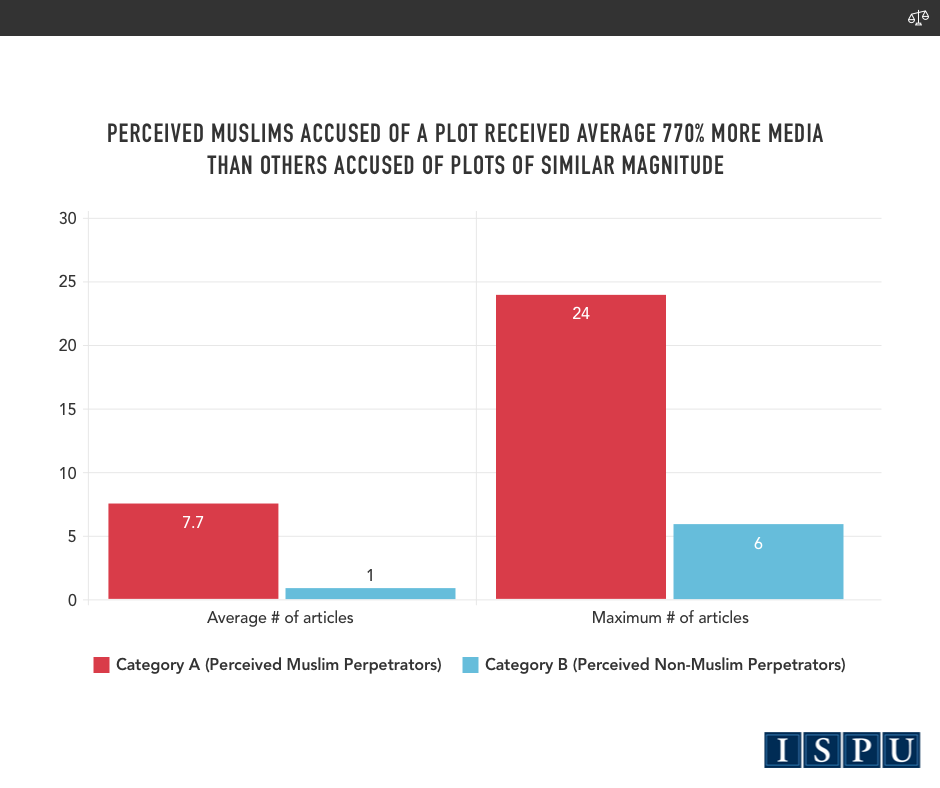

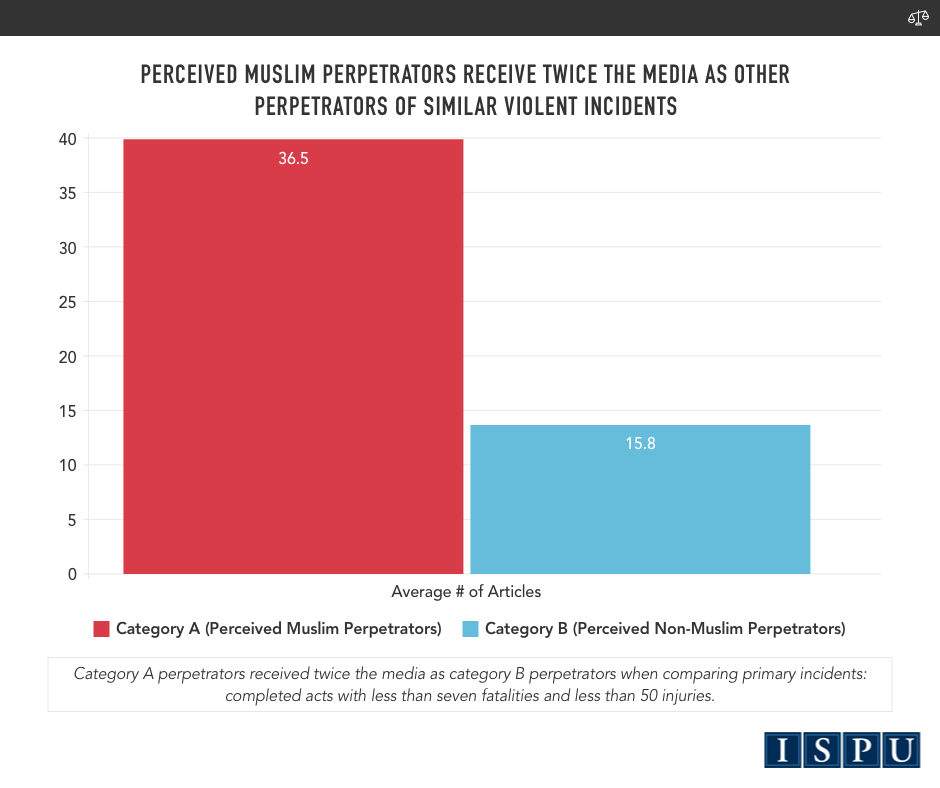

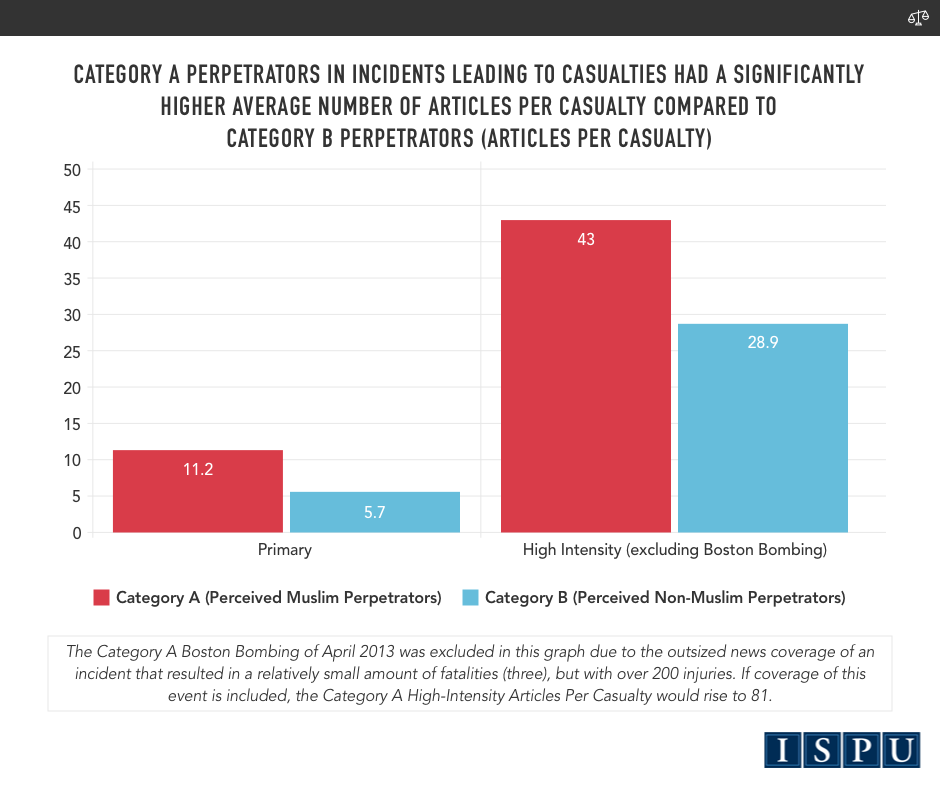

In this apples-to-apples study, ISPU’s research reveals perceived Muslim perpetrators of violence are subject to more severe legal charges, up to three times the prison sentence, and more than seven times the media coverage compared to non-Muslim perpetrators. Perpetrators perceived as Muslim are also much more likely to be targeted for undercover law enforcement operations providing them with weapons or fake explosives.

Executive Summary & Key Findings

Executive Summary | Equal Treatment?: Measuring the Legal and Media Responses to Ideologically Motivated Violence in the United States

This is an executive summary of the report Eq

05 April, 2018Key Findings | Equal Treatment?: Measuring the Legal and Media Responses to Ideologically Motivated Violence in the United States

This is a summary of the key findings of Equal Tre

05 April, 2018

.

Dive into the Data

Video

.

Equal Treatment? Not Quite…

Watch this short video for a quick summary of some of the key findings of our Equal Treatment? report. And share with a friend if you learned something new!

What We Did

Equal Treatment? examines two categories of perpetrators in both the media and legal analyses:

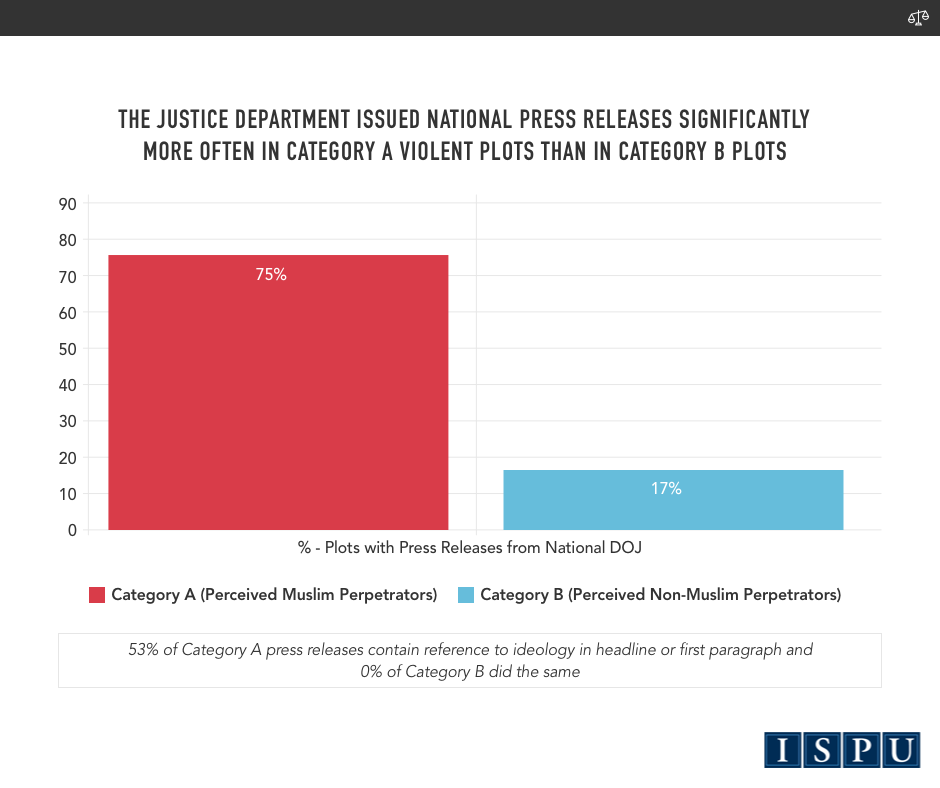

- CATEGORY A: Individuals committing or plotting violent acts who are perceived to be Muslim, allegedly acting in the name of Islam.

- CATEGORY B: Individuals committing or plotting violent ideologically motivated acts who are not perceived to be Muslim and motivated by another ideology.

Cases examined in both analyses were divided into three categories:

- PRIMARY INCIDENTS: Causing two or more fatalities (one fatality was excluded, as it typically means the death of the perpetrator only)

- HIGH-INTENSITY INCIDENTS: Causing at least seven fatalities or at least 50 injuries. This category is the upper extremity of combined fatalities and injuries in the set analyzed, and is grouped to allow better comparison

- VIOLENT PLOTS: Where the planned offense is not executed, but where there is sufficient evidence to bring prosecution

Incident Selection

IMV incidents associated with perpetrators of both categories were selected from existing, published datasets of ideologically motivated violence. Based on a combination of these existing datasets, United States-based IMV incidents from 2002 to 2015 resulting in two or more fatalities were included. We also included a set of violent ideological plots that were prevented or foiled prior to completion, either by law enforcement investigation or through a “sting” operation. The violent plots included bomb plots and firearms plots. As used in this report “violent plot” and “plot” are interchangeable. The goal of selecting this set of incidents was not to create a new or comprehensive database of IMV acts. Instead, the purpose was to facilitate as best as possible an “apples to apples” study, i.e., to compare Category A and Category B perpetrators whose conduct and impact were similar in severity and quality. Incident selection was done prior to any analysis and was not changed after analysis began.

Are We Comparing Apples to Apples?

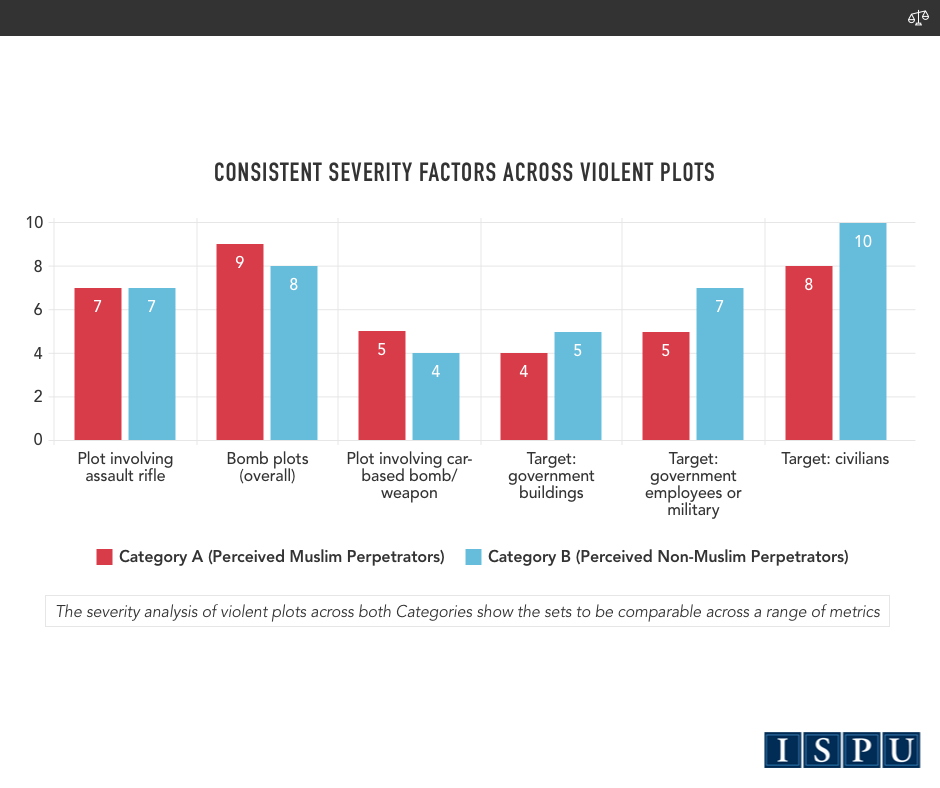

Some may suggest that differences in nature and scale of offenses may make it difficult to analyze or draw inferences from the legal and media treatment of the two categories of perpetrators. While we cannot rule out that such differences might partly explain some differences in outcome, we have taken a number of steps to ensure as close to an “apples to apples” comparison as possible.

Here are the factors that have been recorded and accounted for in analyzing incidents:

Fatalities: An incident resulting a greater number of fatalities is generally more severe than one with fewer.

Weapon used: The weapon used in a violent incident or planned for use in a violent plot indicates the intended scale of the violent act.

Intended outcome: This measures the level of harm the perpetrator aimed to cause, as alleged by law enforcement.

Target of incident: The type of target is recorded in incidents, such as whether it is a religious community, a racial or ethnic group, an LGBT individual or group, or the government.

Existence of co-perpetrators: Where applicable, any accused co-perpetrators or co-conspirators are recorded.

Equal Treatment? in the News

Equal Treatment? in the News

Meet the Research Team

Meet the Research Team

We would like acknowledge the following for their consultation:

Amna Akbar, JD, University of Michigan; Assistant Professor of Law at The Ohio State University Mortiz College of Law

Erik Bleich, PhD, Political Science and Government, Harvard University; Charles A. Dana Professor of Political Science at Middlebury College

Aloke Chakravarty, JD, Emory University School of Law; former Assistant U.S. Attorney in the U.S. Attorney’s Office for the District of Massachusetts

Michael German, JD, Northwestern University Law School; fellow with the Brennan Center for Justice’s Liberty and National Security Program

Adam Johnson, Associate editor of Alternet.org; contributing writer for Fair Media Watch, the Nation, Alternet, and the Los Angeles Times

Faiza Patel, JD, New York University School of Law; co-director of the Brennan Center’s Liberty and National Security Program

Stephen Piggott, Senior Research Analyst with the Southern Poverty Law Center

Wadi Said, JD, Columbia University School of Law; Professor of Law at the University of South Carolina School of Law

Hina Shamsi, JD, Northwestern University School of Law; director of the ACLU National Security Project; lecturer-in-law at Columbia Law School

Shirin Sinnar, JD, Stanford Law School; Associate Professor of Law and John A. Wilson Faculty Scholar at Stanford Law School

Manar Waheed, JD, Brooklyn Law School; former Deputy Policy Director for Immigration at the White House Domestic Policy Council in the Obama Administration; Legislative and Advocacy Counsel at the ACLU

Vince Warren, JD, Rutgers School of Law; executive director of the Center for Constitutional Rights

Dina Zingaro, Associate producer at CBS News 60 Minutes

Imraan Siddiqi, Executive Director, Council on American Islamic Relations Arizona

Charles Kurzman, Professor of Sociology at the University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill

David Schanzer, Director of the Triangle Center on Terrorism and Homeland Security at Duke University

Rebecca Lenn, Media Matters for America