Trust Must be Earned: Vaccine Uptake and Hesitancy Among American Muslims

September 16, 2021 | BY MEIRA NEGGAZ

SUMMARY

A plurality of American Muslims wished to get the COVID vaccine as soon as they could. But a sizable segment of the Muslim population expresses vaccine hesitancy. Key intra-community differences mirror those seen among Americans broadly. Opportunities for trust building, targeted education and further research are key.

Roughly one year after the start of the COVID-19 pandemic, and after much politicization of the COVID response, vaccines became available to the general American public. The vaccines developed were proven to be effective and safe, and were given emergency use authorization by the Food and Drug Administration (FDA). And, many Americans excitedly rolled up their sleeves and started dreaming about their lives resuming a semblance of pre-pandemic normal.

But, just as some couldn’t wait to get their shots, other Americans were hesitant, concerned, scared even. It is within this context that the Institute for Social Policy and Understanding (ISPU) explored vaccine uptake and hesitancy among American Muslims and the general American public. Given that we fielded our survey from March to early April of 2021, our findings reflect a moment in time. A moment when vaccines were fairly new, when they were harder to access, and when medical and other essential personnel, older Americans, and those at high risk were eligible to get them.

Trust Must be Earned: Vaccine Uptake and Hesitancy Among American Muslims

September 16, 2021 | BY MEIRA NEGGAZ

SUMMARY

A plurality of American Muslims wished to get the COVID vaccine as soon as they could. But a sizable segment of the Muslim population expresses vaccine hesitancy. Key intra-community differences mirror those seen among Americans broadly. Opportunities for trust building, targeted education and further research are key.

Roughly one year after the start of the COVID-19 pandemic, and after much politicization of the COVID response, vaccines became available to the general American public. The vaccines developed were proven to be effective and safe, and were given emergency use authorization by the Food and Drug Administration (FDA). And, many Americans excitedly rolled up their sleeves and started dreaming about their lives resuming a semblance of pre-pandemic normal.

But, just as some couldn’t wait to get their shots, other Americans were hesitant, concerned, scared even. It is within this context that the Institute for Social Policy and Understanding (ISPU) explored vaccine uptake and hesitancy among American Muslims and the general American public. Given that we fielded our survey from March to early April of 2021, our findings reflect a moment in time. A moment when vaccines were fairly new, when they were harder to access, and when medical and other essential personnel, older Americans, and those at high risk were eligible to get them.

Less Vaccine Hesitancy Among Those With Personal Experience With COVID

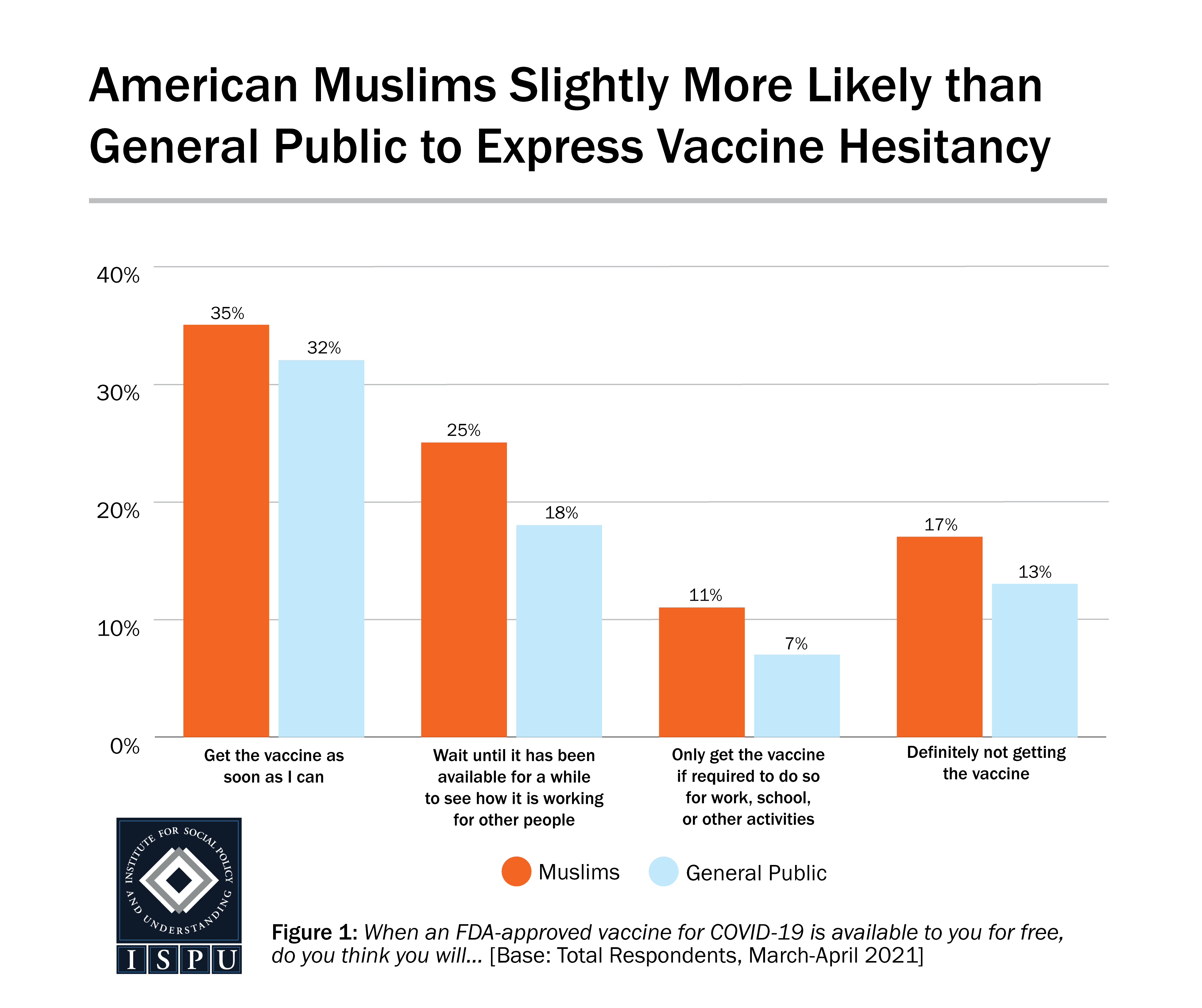

We found that a sizable percentage, a full third, of American Muslims and members of the American general public wished to get the COVID vaccine as soon as they could (35% and 32%). One reason why Muslims may have been eager early on to get vaccinated is that one in ten are medical workers contributing to the COVID response.

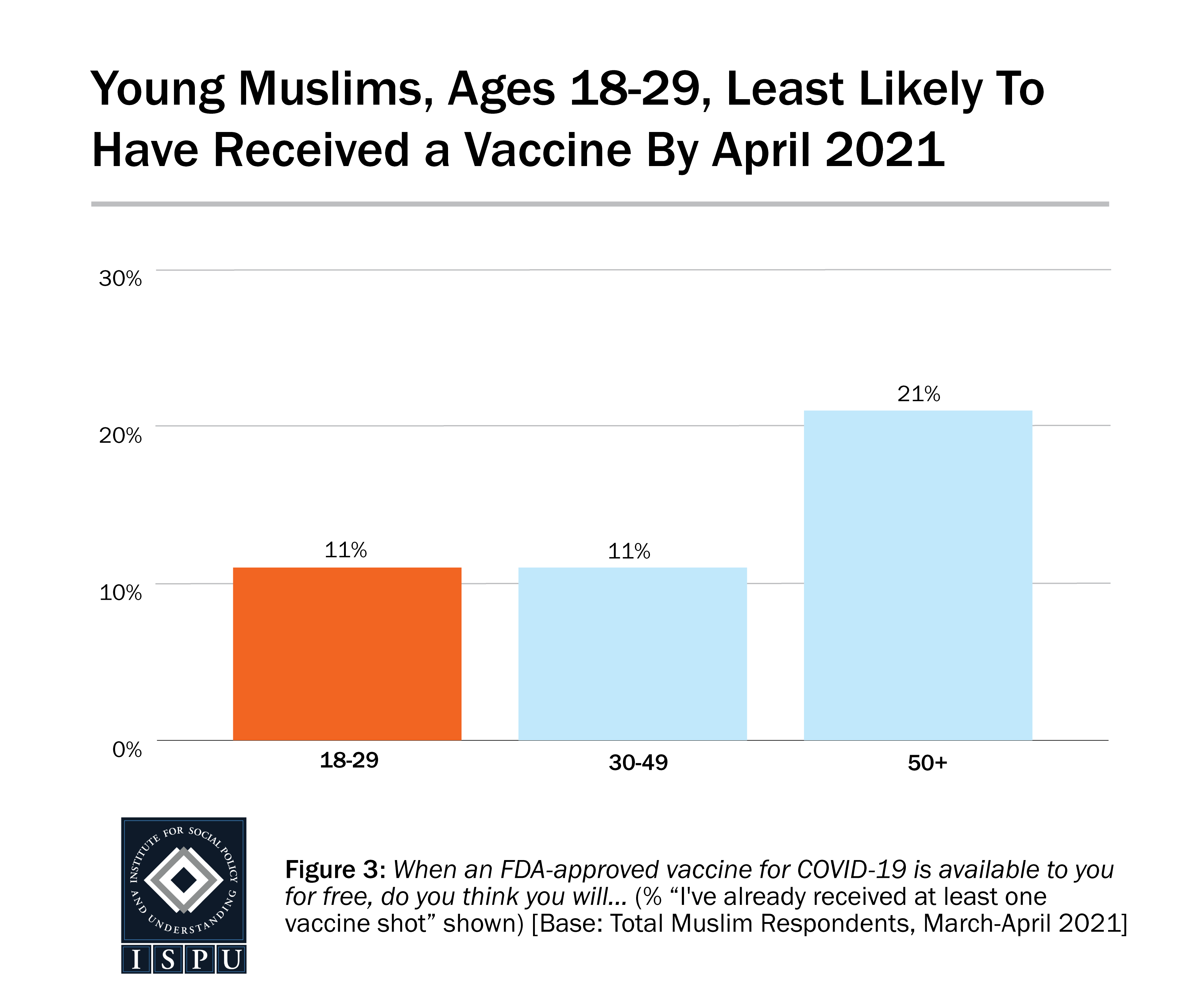

Despite this, Muslims were less likely to have already received at least one shot as compared to the general public (13% versus 30%) as of March 22 – April 8, 2021 when the survey was fielded. This may, in part, be due to the youthfulness of the American Muslim population (41% of American Muslims are under the age of 30, and 81% are under the age of 50) as younger people were largely not yet eligible at the time the survey was fielded. In fact, we found that the Muslims aged 18-29 were less likely than older Muslims to have received at least one shot at the time they completed the survey (March-April 2021). Muslims who knew someone who had died of COVID (and who were eligible to receive a vaccine at that time) were twice as likely to have received their first shot (19% versus 10%). So, experiencing the negative effects of COVID may have spurred some people on to try to protect themselves and others through vaccination.

While a third of Muslims were eager to get vaccinated, a sizable percentage expressed vaccine hesitancy. Muslims were more likely than the general public to wish to wait and see how it is working for other people (25% versus 18%), only get the vaccine if required to do so (11% versus 7%) and say they would definitely not get vaccinated (17% versus 13%). One reason for this hesitancy may be the institutional discrimination faced by Muslims within the healthcare system. ISPU’s American Muslim Poll found that among the 60% of Muslims who have experiened religious based discrimination in the past year, and among those who experienced bias, a full quarter have experienced it within the healthcare system. However, those Muslims who had at some point tested positive for COVID were less likely than those who had never tested positive to take a wait and see approach (17% versus 28%). Once again, experiencing COVID may have reduced hesitancy.

Views of Vaccine Differ By Gender, Age and Race

Vaccine hesitancy among Muslims in some respects mirrors vaccine hesitancy among the general public, with views on COVID-19 vaccination among Muslims as diverse as the American Muslim population itself.

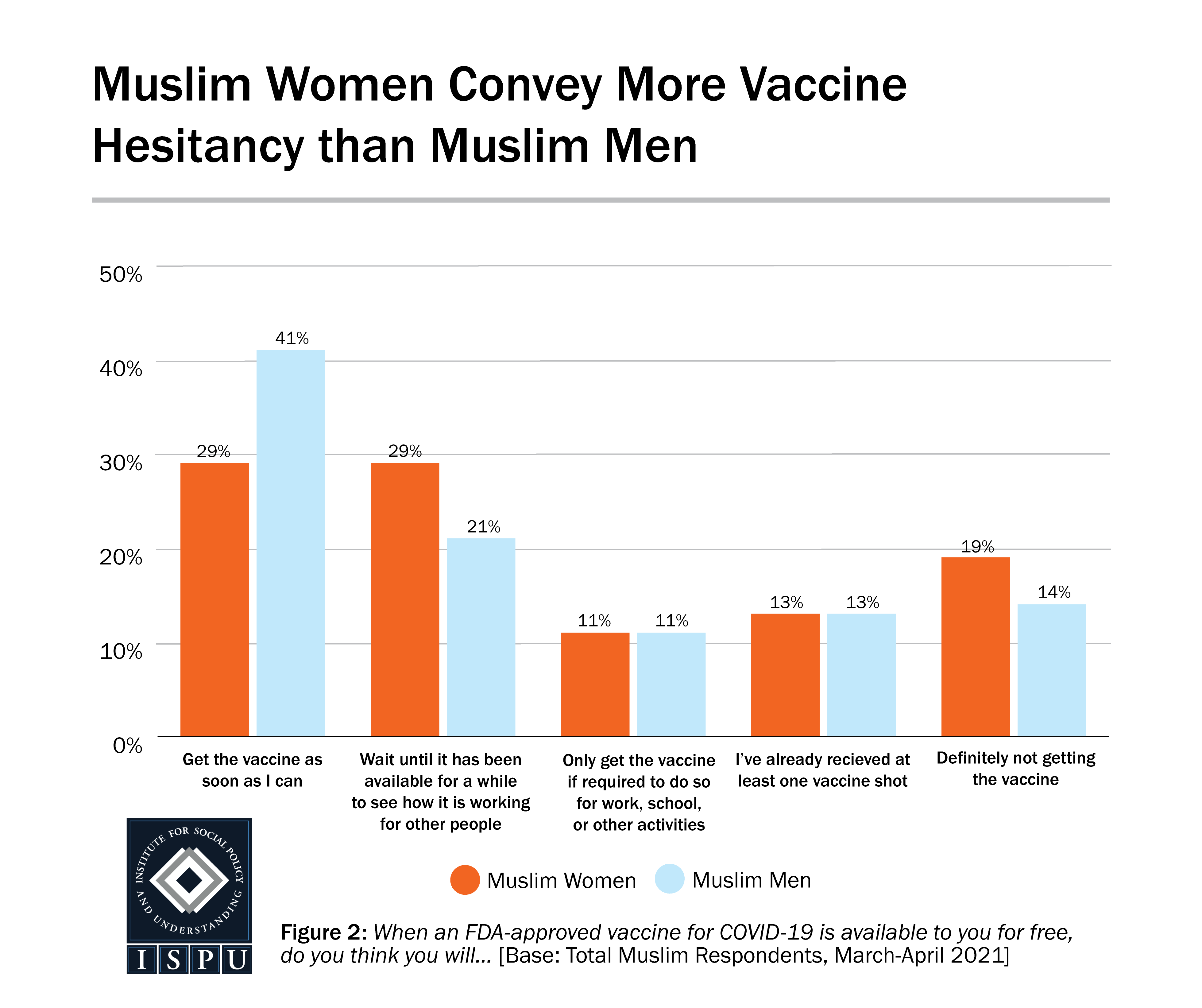

Muslim men were more likely to wish to be vaccinated as soon as they could as compared to Muslim women (41% versus 29%). While we don’t have data on why these gender differences exist, one possible explanation relates to reproductive concerns (which studies have so far shown to be unfounded). Indeed, Muslim women are more likely than Muslim men to wish to wait a little while to see how it is working for others (29% verus 21%). These patterns reflect what we find in the general public, with women more likely than men to report they will definitely not get the vaccine (18% versus 7%).

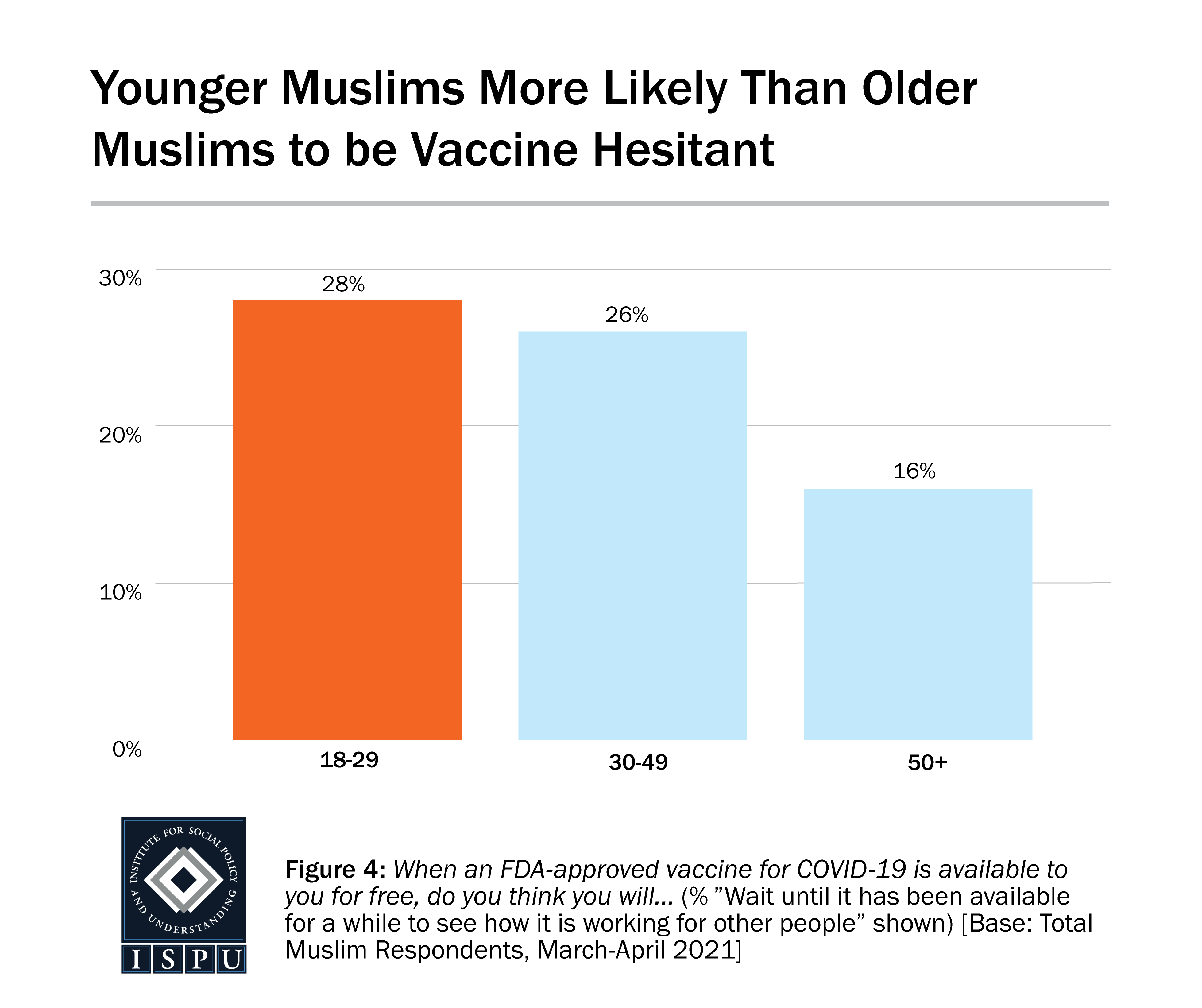

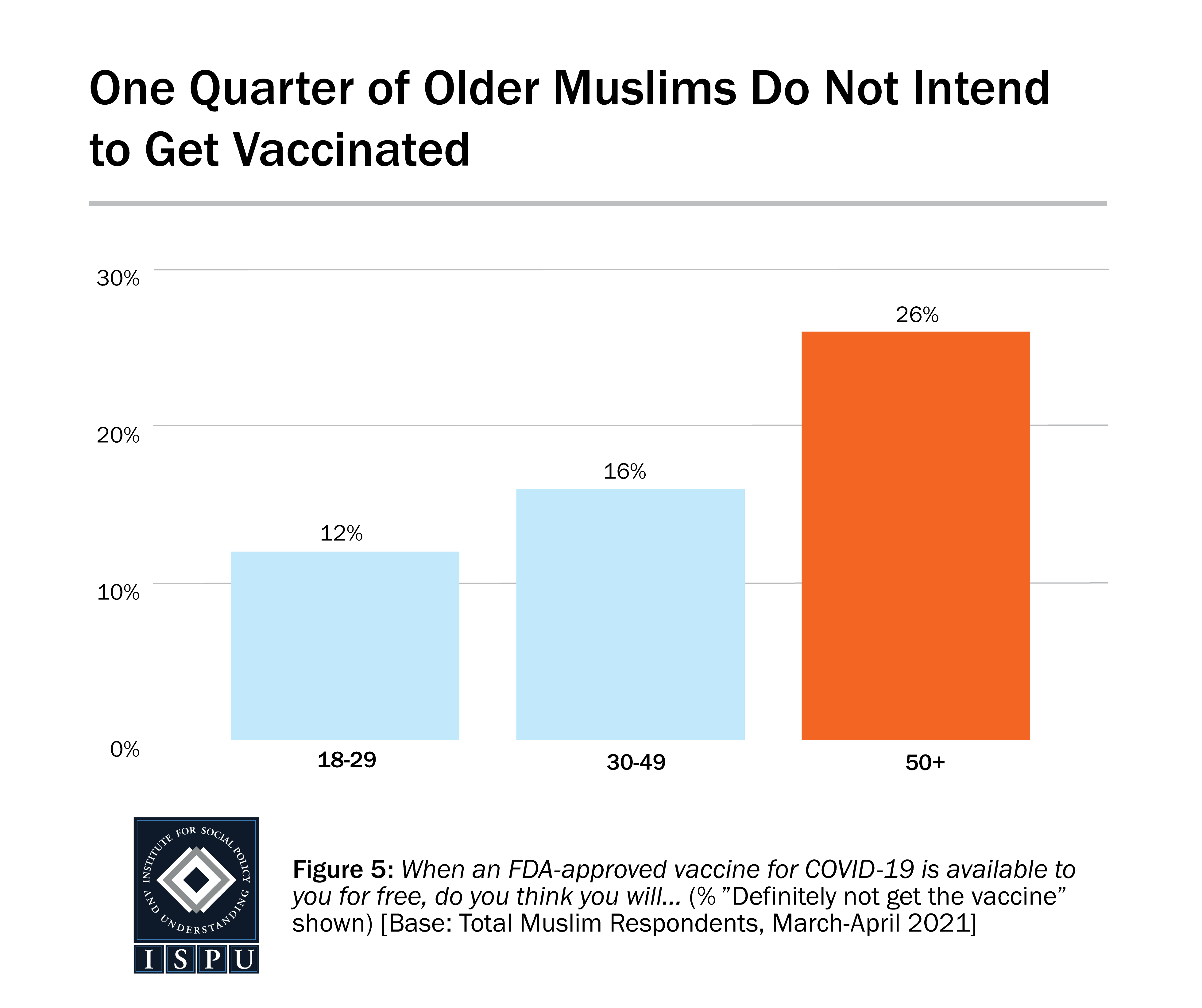

Younger Muslims, aged 18-29 and 30-49, are more likely to be vaccine hesitant than Muslims aged 50 and above (28% and 26% versus 16%), saying they will wait to see how it works for others. This echoes findings from the general public. But, a sizable segment of older Muslims were more likely to have no intention to get vaccinated (26% versus 12% and 16% for 18-29 and 30-49 year olds, respectively). This has implications for both individuals and our healthcare system, as older people generally are at higher risk from serious complications.

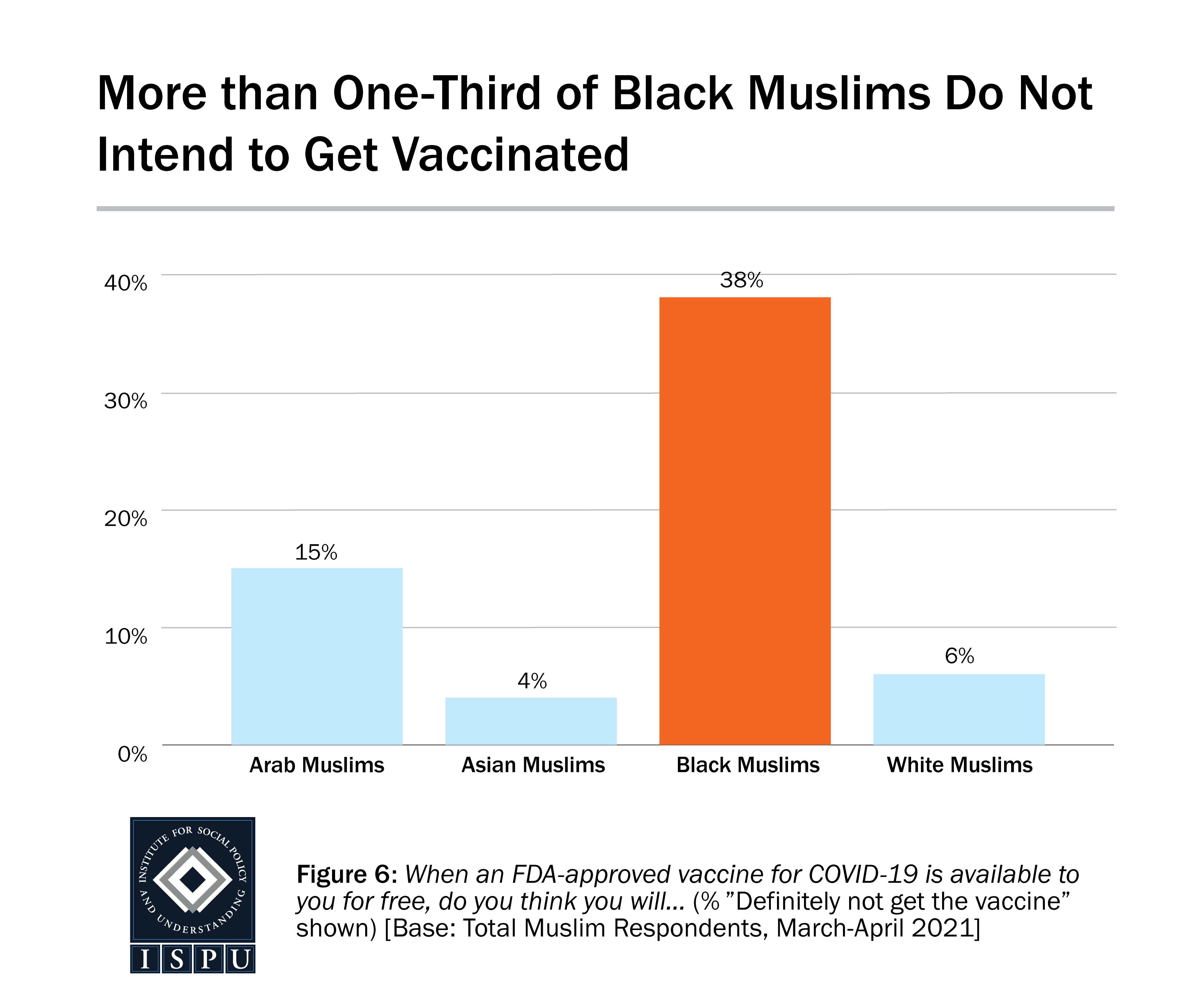

Muslims who identify as either Asian or white were more likely than Muslims who identify as Arab or Black to wish to get vaccinated as soon as they could (42% of both Asian and white Muslims versus 28% of Arab and 29% of Black Muslims). And Muslims who identify as Black were least likely to have already received at least one vaccine dose (3% versus more than 16% for Asian, Arab, and white Muslims) and most likely to say they do not intend to get vaccinated (38% versus less than 15% for Asian, Arab, and white Muslims). This mirrors vaccine hesitancy among Black Americans more broadly and likely reflects a number of factors including pervasive inequity and mistrust of systems which have far too often failed and harmed Black Americans.

As the COVID-19 pandemic rages on, with infections, hospitalizations, and deaths trending in the wrong direction, public health experts argue that vaccines are the most important tools we have in our toolbox for saving lives and returning to a semblance of normal. But, real challenges exist, in part due to institutionalized discrimination and centuries of racism. As part of the fabric of American society, Muslims mirror vaccine uptake and hesitancy seen in the general public, with some notable differences.

If we are to decrease vaccine hesitancy and increase vaccine uptake, trust must be earned within communities who have historically and in the present experienced discrimination and harm with healthcare systems (and beyond). Establishing and maintaining this trust will require a sincere commitment to changing systems and deeply engaging with communities. These efforts will require time and dedication. Herein lies the dilemma—we need time to undo harm and build better trust, but the pandemic introduces an urgency that doesn’t readily allow the time needed to do this. As a result, lives may be lost and life disrupted in the process. Further research is also needed in what defines and facilitates trust in the American Muslim community, so public officials and other can better build health equity and wellness.

Meira Neggaz is the Executive Director at ISPU, where she is responsible for the institution’s overall leadership, strategy, and growth. Meira works to build and strengthen ISPU, to cultivate relationships with community leaders, policy makers, scholars, partner institutions and stakeholders, and to broaden the reach and impact of ISPU’s research. Learn more about Meira→