.

The American Mosque 2020: Growing and Evolving

Report 2 of the US Mosque Survey 2020:

Perspectives and Activities

JULY 29, 2021 | BY DR. IHSAN BAGBY

SUMMARY

The US Mosque Survey 2020 is a comprehensive statistical study of mosques located in the United States. The survey is an ongoing decadal survey which was conducted previously in 2000 and 2010. Reports featuring the results will occasionally include results from a 1994 survey which was conducted by the Islamic Resource Center, using the same methodology as the US Mosque Surveys.

The purpose of the US Mosque Survey is to conduct a scientific study that will generate accurate information about most aspects of the American mosque. The goal is to provide a detailed portrait of the American mosque to dispel misconceptions and to help mosque leaders and participants better understand their mosque, hopefully leading to improvements.

.

Introduction

The US Mosque Survey 2020 is a comprehensive statistical study of mosques located in the United States. The US Mosque Survey is an ongoing decadal survey which was conducted previously in 2000 and 2010. This report will occasionally include results from a 1994 survey which was conducted by the Islamic Resource Center, using the same methodology as the US Mosque Surveys.

The purpose of the US Mosque Survey is to conduct a scientific study that will generate accurate information about most aspects of the American mosque. The goal is to provide a detailed portrait of the American mosque to dispel misconceptions and to help mosque leaders and participants better understand their mosque, hopefully leading to improvements.

All of the US Mosque Surveys (2000, 2010, and 2020) were conducted in collaboration with a larger study of American congregations called Faith Communities Today (FACT), which is a project of the Cooperative Congregational Studies Partnership (CCSP), a multi-faith coalition of numerous denominations and faith groups, headquartered at Hartford Seminary. The strategy of FACT is to develop a common questionnaire and then have the member faith groups use that questionnaire to conduct a survey of their respective congregations. The US Mosque Surveys took the FACT common questionnaire and modified it to fit the mosque context.

The primary sponsors of the US Mosque Survey 2020 include many organizations: Islamic Society of North America (ISNA), Center on Muslim Philanthropy, Institute for Social Policy and Understanding (ISPU), and the Association of Statisticians of American Religious Bodies (ASARB). Other important supporters include Intuitive Solutions, International Institute of Islamic Thought (IIIT), Islamic Circle of North America’s Council for Social Justice, Council on American-Islamic Relations (CAIR), and Hartford Institute for Religion Research (Hartford Seminary).

The lead researcher for the Mosque Survey is Dr. Ihsan Bagby. The Research Committee for the Mosque Survey includes:

-

- Ihsan Bagby, Associate Professor of Islamic Studies, University of Kentucky

- Dalia Mogahed, Director of Research, ISPU

- Besheer Mohamed, Senior Researcher, Pew Research Center

- Scott Thumma, Professor of Sociology of Religion, Hartford Seminary

- Shariq Siddiqui, Director, Muslim Philanthropy Initiative, Indiana University

- Riad Ali, President and Founder, American Muslim Research and Data Center

- Zahid Bukhari, Director, ICNA Council for Social Justice

Research Methodology

The first phase of the Mosque Survey was a count of all mosques, which was conducted from June to November 2019. Starting from the 2010 mosque database, an initial internet search was conducted to verify mosques, identify new mosques, and eliminate mosques that no longer exist. This internet search depended primarily on the excellent databases found on the websites of Muslim Guide and Salatomatic. Mosques were verified via the mosques’ websites, Google Maps, and a phone call. The internet search resulted in an initial count of 2948. After the internet search, a first-class (address correction) letter and a short questionnaire were sent to all the mosques. Various options for completing the questionnaire were offered, including an online version. Of the 2948 mailings, 164 responses were received—a 5.5% response rate. This low response rate is the rationale for not depending on an online version for the comprehensive survey. Returned mail was checked with Google Maps and a general internet search. The final result was a count of 2769 mosques.

The second phase was the comprehensive survey conducted via telephone interview of a mosque leader using a long questionnaire. The comprehensive survey entailed a random sampling from the list of 2769 mosques. To achieve the goal of a margin of error of +/- 5%, 337 questionnaires had to be completed. The sample of mosques was stratified by state, such that each state had a set number of mosques for which the questionnaire had to be completed. The Mosque Survey randomly sampled 700 mosques, and 470 questionnaires were completed, fulfilling the target for each state. The work of completing the questionnaires started in November 2019 and ended in October 2020. The COVID-19 crisis made the task of finding a mosque leader more difficult; thus, completion of the survey was delayed.

The results of the US Mosque Survey are all pre-COVID. Thus, interviewers asked the mosque leaders about the situation of their mosques before the outbreak of COVID-19.

For the Mosque Survey, mosques were defined as a Sunni or Shi’ite Muslim organization that organizes Jum’ah prayer, conducts other Islamic activities, and controls the space in which activities are held.* This definition would include “musallas” which have an organization that does more than just conduct Jum’ah prayers. This definition excludes those places where only Jum’ah prayer is held, like a hospital or airport. Some Shi’ite religious organizations do not hold Jum’ah prayer due the absence of a resident scholar or because they consider themselves an Imambargah or Hussainiya. These Shi’ite organizations were classified as mosques. The Mosque Survey did not include organizations outside of the Sunni and Shi’ite American Muslim community like the Nation of Islam, Moorish Science Temple, Ismailis, and Ahmadiyyah.

Thanks go to the numerous interviewers who were hired to conduct the mosque count and interview mosque leaders. Special thanks to Intuitive Solutions under Tayyab Yunus who supplied several excellent interviewers. Thanks also to the Islamic Shura Council of Southern California for assisting the Mosque Survey in identifying mosque leaders and supplying interviewers.

The results of the US Mosque Survey 2020 are divided into two reports. Report 1 focuses on essential statistics, mosque participants, mosque administration, and the basic characteristics of Shi’ite mosques. Report 2 focuses on Islamic approaches in understanding Islam, perspectives of mosque leaders on American society, mosque activities, women in the mosque, and the perspectives and activities of Shi’ite mosques.

The results recorded in the two reports include both Sunni and Shi’ite mosques. A separate section on Shi’ite mosques is included in both reports.

Note: Percentages throughout this report may not total 100% due to rounding.

SUMMARY

ISPU’s fifth annual poll showcases American Muslim perspectives within the context of their nation’s faith landscape. Fielded during a national lockdown due to COVID-19, American Muslim Poll 2020: Amid Pandemic and Protest provides researchers, policymakers, and the public insights and analysis into the attitudes and policy preferences of American Muslims, Jews, Catholics, Protestants, white Evangelicals, the non-affiliated, and the general public. For the third year, we track the National American Islamophobia Index, measuring how much the public endorses anti-Muslim tropes. New this year: our researchers track five years of American Muslim civic engagement trends, examine the level of support for faith activists to form coalitions with social and political groups, and present new research on institutionalized versus interpersonal discrimination.

DOWNLOADS

Introduction

The US Mosque Survey 2020 is a comprehensive statistical study of mosques located in the United States. The US Mosque Survey is an ongoing decadal survey which was conducted previously in 2000 and 2010. This report will occasionally include results from a 1994 survey which was conducted by the Islamic Resource Center, using the same methodology as the US Mosque Surveys.

The purpose of the US Mosque Survey is to conduct a scientific study that will generate accurate information about most aspects of the American mosque. The goal is to provide a detailed portrait of the American mosque to dispel misconceptions and to help mosque leaders and participants better understand their mosque, hopefully leading to improvements.

All of the US Mosque Surveys (2000, 2010, and 2020) were conducted in collaboration with a larger study of American congregations called Faith Communities Today (FACT), which is a project of the Cooperative Congregational Studies Partnership (CCSP), a multi-faith coalition of numerous denominations and faith groups, headquartered at Hartford Seminary. The strategy of FACT is to develop a common questionnaire and then have the member faith groups use that questionnaire to conduct a survey of their respective congregations. The US Mosque Surveys took the FACT common questionnaire and modified it to fit the mosque context.

The primary sponsors of the US Mosque Survey 2020 include many organizations: Islamic Society of North America (ISNA), Center on Muslim Philanthropy, Institute for Social Policy and Understanding (ISPU), and the Association of Statisticians of American Religious Bodies (ASARB). Other important supporters include Intuitive Solutions, International Institute of Islamic Thought (IIIT), Islamic Circle of North America’s Council for Social Justice, Council on American-Islamic Relations (CAIR), and Hartford Institute for Religion Research (Hartford Seminary).

The lead researcher for the Mosque Survey is Dr. Ihsan Bagby. The Research Committee for the Mosque Survey includes:

-

- Ihsan Bagby, Associate Professor of Islamic Studies, University of Kentucky

- Dalia Mogahed, Director of Research, ISPU

- Besheer Mohamed, Senior Researcher, Pew Research Center

- Scott Thumma, Professor of Sociology of Religion, Hartford Seminary

- Shariq Siddiqui, Director, Muslim Philanthropy Initiative, Indiana University

- Riad Ali, President and Founder, American Muslim Research and Data Center

- Zahid Bukhari, Director, ICNA Council for Social Justice

Research Methodology

The first phase of the Mosque Survey was a count of all mosques, which was conducted from June to November 2019. Starting from the 2010 mosque database, an initial internet search was conducted to verify mosques, identify new mosques, and eliminate mosques that no longer exist. This internet search depended primarily on the excellent databases found on the websites of Muslim Guide and Salatomatic. Mosques were verified via the mosques’ websites, Google Maps, and a phone call. The internet search resulted in an initial count of 2948. After the internet search, a first-class (address correction) letter and a short questionnaire were sent to all the mosques. Various options for completing the questionnaire were offered, including an online version. Of the 2948 mailings, 164 responses were received—a 5.5% response rate. This low response rate is the rationale for not depending on an online version for the comprehensive survey. Returned mail was checked with Google Maps and a general internet search. The final result was a count of 2769 mosques.

The second phase was the comprehensive survey conducted via telephone interview of a mosque leader using a long questionnaire. The comprehensive survey entailed a random sampling from the list of 2769 mosques. To achieve the goal of a margin of error of +/- 5%, 337 questionnaires had to be completed. The sample of mosques was stratified by state, such that each state had a set number of mosques for which the questionnaire had to be completed. The Mosque Survey randomly sampled 700 mosques, and 470 questionnaires were completed, fulfilling the target for each state. The work of completing the questionnaires started in November 2019 and ended in October 2020. The COVID-19 crisis made the task of finding a mosque leader more difficult; thus, completion of the survey was delayed.

The results of the US Mosque Survey are all pre-COVID. Thus, interviewers asked the mosque leaders about the situation of their mosques before the outbreak of COVID-19.

For the Mosque Survey, mosques were defined as a Sunni or Shi’ite Muslim organization that organizes Jum’ah prayer, conducts other Islamic activities, and controls the space in which activities are held.* This definition would include “musallas” which have an organization that does more than just conduct Jum’ah prayers. This definition excludes those places where only Jum’ah prayer is held, like a hospital or airport. Some Shi’ite religious organizations do not hold Jum’ah prayer due the absence of a resident scholar or because they consider themselves an Imambargah or Hussainiya. These Shi’ite organizations were classified as mosques. The Mosque Survey did not include organizations outside of the Sunni and Shi’ite American Muslim community like the Nation of Islam, Moorish Science Temple, Ismailis, and Ahmadiyyah.

Thanks go to the numerous interviewers who were hired to conduct the mosque count and interview mosque leaders. Special thanks to Intuitive Solutions under Tayyab Yunus who supplied several excellent interviewers. Thanks also to the Islamic Shura Council of Southern California for assisting the Mosque Survey in identifying mosque leaders and supplying interviewers.

The results of the US Mosque Survey 2020 are divided into two reports. Report 1 focuses on essential statistics, mosque participants, mosque administration, and the basic characteristics of Shi’ite mosques. Report 2 focuses on Islamic approaches in understanding Islam, perspectives of mosque leaders on American society, mosque activities, women in the mosque, and the perspectives and activities of Shi’ite mosques.

The results recorded in the two reports include both Sunni and Shi’ite mosques. A separate section on Shi’ite mosques is included in both reports.

Note: Percentages throughout this report may not total 100% due to rounding.

.

Major Findings

-

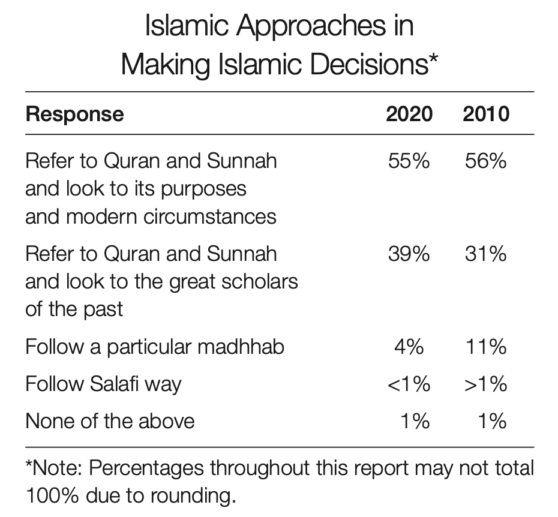

- American mosque leaders lean toward an understanding of Islam that adheres to the foundational, textual sources of Islam (Qur’an and Sunnah) but are open to interpretations that look to the purposes of Islamic law (i.e., looking to the spirit and wisdom of the law) and modern circumstances: 55% of mosques follow this approach. This approach can be viewed as a “contextual” approach. The other 44% of mosques follow approaches that adhere to the foundational sources but prefer interpretations embedded in traditional views of the past—a “traditional” approach. Although this approach is quite varied, it tends to be more religiously conservative.

- Mosques that follow the “contextual” approach by looking to the purposes of Islamic law score significantly higher in their mosques’ community involvement, political involvement, and women-friendly position.

- The literal, extremely conservative Salafi approach (akin to Wahhabi thought) has largely disappeared among American mosques: Less than 1% of mosques follow this approach.

- The American mosque is virtually unanimous in approval of involvement in American civic and political life: 98% agree with civic engagement, and 95% agree with political participation. Isolationism and extreme alienation from America are extremely rare among American mosques. No matter the Islamic approach, nationality/ethnicity of attendees, mosque size, or location, the American mosque embraces involvement in American society.

-

- The vast majority of mosque leaders do not feel that American society is hostile to Islam or that American society is immoral: only 18% agree that American society is hostile, and only 19% agree that American society is immoral. These results point to a low level of negativity toward American society. These percentages are very similar to the percentages in 2010, indicating that the Trump years have not affected the views of mosque leaders.

- The typical American mosque hosts a wide variety of worship, educational, and group activities every day throughout the week. The American mosque has embraced the ideal that a mosque is to be a worship-community center that strives to be a nexus for all types of activities for the entire mosque community. The American mosque is not simply a place of worship as it is in some majority Muslim countries.

- Activities targeting young adults (18-35) lag in comparison with churches and synagogues; nevertheless, there was some improvement from the 2010 Mosque Survey.

- Most American mosques are involved in their neighborhoods and cities: 66% have a food pantry or food distribution program; 50% are involved in social justice activities; 76% participate in interfaith educational programs; and 59% have been involved in an interfaith community service project.

- American mosques are engaged in political activities: 54% of mosques hosted voter registration drives in the past 12 months; 51% hosted politicians to visit and speak at their mosques; and 37% held an event or class to discuss politics.

- Those mosques that believe American society is immoral score slightly lower in political involvement: Only 18% of mosques that agree that America is immoral score high in political involvement as opposed to 27% of mosques that do not agree or are neutral about America’s immorality.

- The issue of women in the mosque has taken center stage as a topic of debate within the American Muslim community. The results of the US Mosque Survey 2020 regarding women are mixed—there is some progress but few major changes.

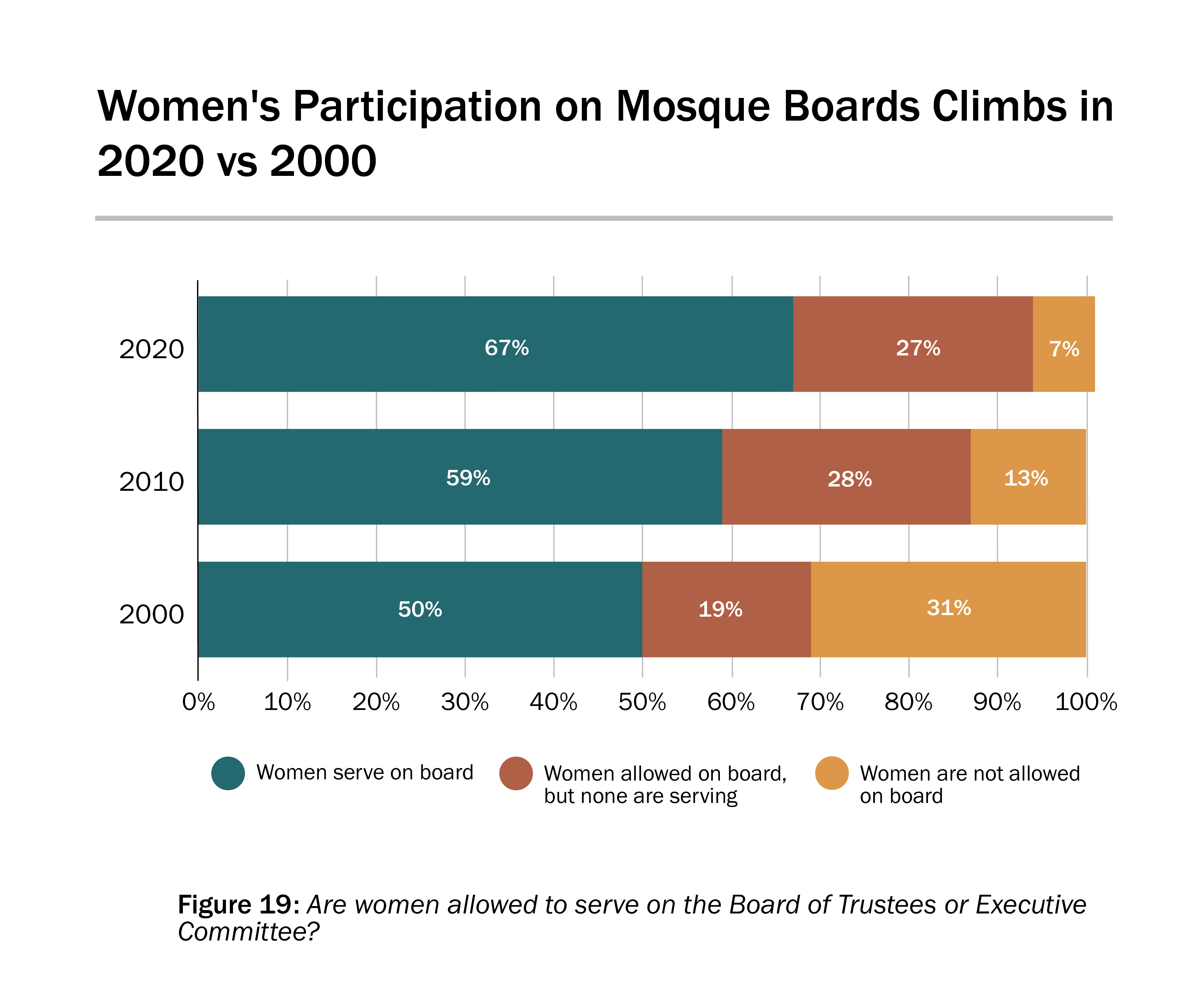

- The progress in women’s issues is that 67% of mosques have women serving on their mosque boards—an increase from 59% in 2010. Those mosques that do not allow women on their boards have dropped to 7% as compared to 31% in 2000 and 13% in 2010. The argument that women should not serve on governing bodies of Muslim organizations has largely been defeated.

- Only 19% of mosques scored excellent as women-friendly mosques, but that is an increase from 14% in 2010. Approximately 49% scored excellent or good in being women-friendly as compared to 37% in 2010.

- African American mosques stand apart in that they score higher than other mosques in these three areas: They are women-friendly, community-involved, and adopt the “contextual approach” to interpreting Islamic law

- Shi’ite mosques are virtually identical to Sunni mosques in all aspects of mosque life except worship activities, which are part of the long-standing traditional differences between Shi’ite and Sunni mosques.

Did You Know?

Report 2 of the US Mosque Survey 2020: Perspectives and Activities is the second of two reports that comprise the complete US Mosque Survey 2020. Report 1 of the US Mosque Survey 2020: Basic Characteristics of the American Mosque was released in June 2021.

US Mosque Survey 2020 Part Two:

Perspectives and Activities

Islamic Approaches

The approach that mosque leaders take in making Islamic decisions is a rough measure of a traditional-to-contextual continuum. The issue of Islamic approach is a question of how a Muslim understands and interprets the foundational sources of Islam—the Qur’an and the Sunnah (the normative practice of the Prophet Muhammad). Do they follow a more traditional interpretation, or do they favor a more contextual approach that takes into account modern circumstances? It should be noted that all of the Islamic approaches of American mosque leaders can be viewed as “conservative” in that they hold to the absolute authority of the foundational sources, Qur’an and Sunnah. However, while holding to the authority of the sources, the question remains as to how to interpret these sources.

This discussion of Islamic approach is framed by Sunni modalities and, thus, does not fit exactly Shi’ite approaches. A discussion of Shi’ite Islamic approaches is found in the last section of this report. All other results of the US Mosque Survey include both Sunni and Shi’ite mosques.

The US Mosque Survey questionnaire offered the option of four approaches in making an Islamic decision.

-

- “Follow a particular madhhab.” A madhhab refers to a school of legal thought that emerged in the classical period of Islamic civilization (most of them coalesced between 700-900 CE). A madhhab for the most part, therefore, defines what is traditional in Islam. Overall, this approach means the mosque leader prefers to follow the traditional way of doing things which often typifies the way it was done in their home countries. This approach tends to be more conservative.

- “Refer to Qur’an and Sunnah and follow an interpretation that follows the opinions of the great scholars of the past.” This approach does look to one madhhab but is open to considering opinions from all the madhhabs and of the great scholars of the past, regardless of which madhhab they adhere to. This approach varies greatly in application, but being focused on the opinions of the past, this approach also tends to be conservative. Since most mosques in America are very diverse, rarely does a mosque have attendees who follow the same madhhab. Consequently, many mosque leaders try to accommodate this diversity by choosing this multi-madhhab approach of following any of the great scholars of the past.

- “Refer to Qur’an and Sunnah and follow an interpretation that takes into account its purposes (maqasid) and modern circumstances.” This approach adheres to the foundational sources of Islam as their authority, but they are open to more flexible interpretations (mainly modern scholars) that look to the overall purposes of the text (i.e., taking into consideration the spirit of Islamic law as well as the letter of the law) and modern circumstances. This approach respects but is not bound to the traditional schools of Islamic law (madhhabs) nor the opinions of the great Islamic scholars of the past. This approach tends to be a more moderate approach.

- “Follow the Salafi minhaj (way of thought).” The Salafi approach is akin to Wahhabi thought and is associated with a more literal understanding of Islam, which corresponds to strictly following the ways of the first three generations (the salaf) of Islam. This approach is typically the most conservative of the other approaches. Salafi thought had its peak in the 1990s in America, but since then it has experienced a steady decline.

The majority of mosques (55%) follow the more flexible approach of taking into account the purposes of Islamic law and modern circumstances. Clearly, the American mosque is not dominated by traditionalism.

The madhhab approach is declining. In 2020, only 4% of mosque leaders followed the madhhab approach, as opposed to 11% in 2010. The only approach that showed an increase is the approach of following the great scholars of the past: 31% in 2010 and 39% in 2020. Apparently, the mosques that preferred to follow one madhhab in the past are now choosing to identify as mosques that follow all madhhabs, which is represented by the approach of following the great scholars of the past.

The Salafi approach has practically disappeared: Less than 1% in the Mosque Survey identified themselves as Salafi.

Looking at mosque ethnicity/nationality and Islamic approaches, there is little movement in the statistics. All of the varied ethnic mosques (an ethnic mosque is one in which the predominant attendees are from a particular ethnic or national group) prefer the flexible approach of considering purposes and modern circumstances. African American mosques have the highest preference for this approach as it is preferred by over three-fourths (76%), which is undoubtedly influenced by the teachings of Imam W. Deen Mohammed.

Another statistic of note is the decrease of the madhhab approach among South Asian mosques (a South Asian mosque is defined as a mosque in which the predominant attendees are from either Pakistan, India, Afghanistan, or Bangladesh). In 2010, 18% of South Asian mosques followed the madhhab approach, but in 2020 that figure was down to 5%. This change in South Asian mosques is apparently the driving force behind the overall decline of madhhab mosques. The assumption is these mosques, which in 2010 chose the madhhab approach, switched in 2020 to follow the great scholars of the past, responding most likely to the greater diversity of attendees in their mosque. The madhhab mosque is now just as likely to be a Turkish or Bosnian mosque, which might bring a different sensibility to what it means to follow a madhhab.

PERSPECTIVES ON AMERICAN SOCIETY

Involvement in American Society

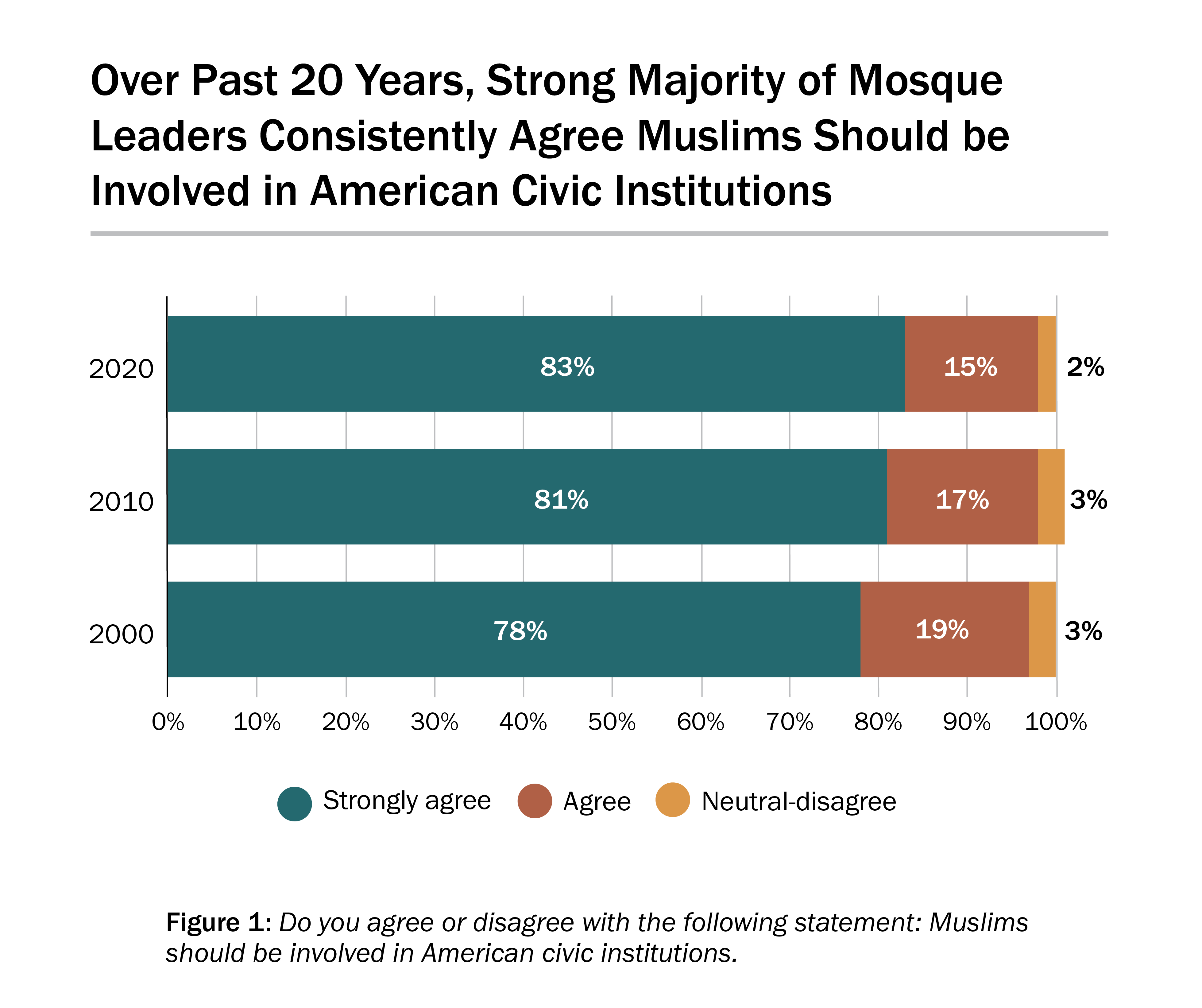

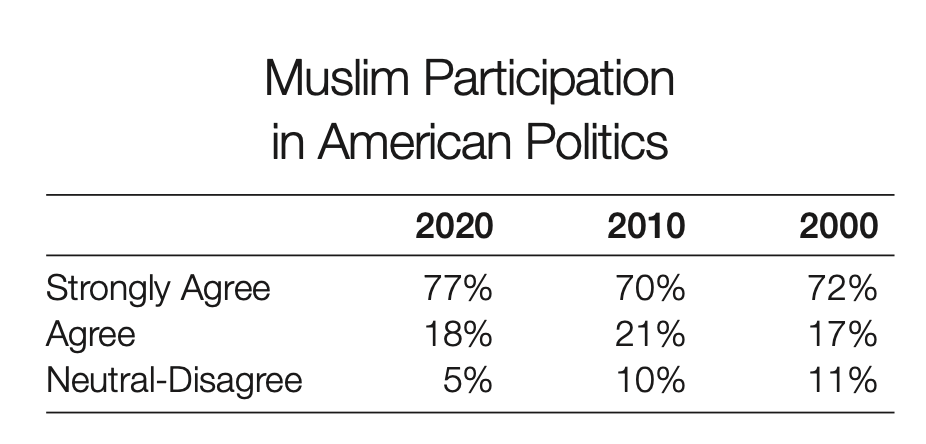

American mosques are virtually unanimous in their endorsement of the proposition that Muslims should be involved in American society in both civic and political life. Over 98% of mosque leaders agree with the statement that Muslims should be involved in American civic institutions; 95% agree that Muslims should be involved in American politics. This consensus on involvement in American society has been in place since 2000, but the percentage of those who “strongly agree” with the idea of involvement has increased since 2000: 78% of mosque leaders “strongly agree” with involvement in civic institutions in 2000, and in 2020 the figure was up to 83%; 72% “strongly agree” with political involvement in 2000, and in 2020 the figure was 77%.

Because of the near unanimity of mosque leaders on involvement in the civic life of American society, there were no significant differences among various types of mosques.

However, the question of participation in American politics does manifest some differences.

While all mosques, no matter the ethnicity, endorse political participation, some African American mosques and those mosques dominated by newer immigrants were slightly less enthusiastic. Among the newer immigrant groups, 66% “strongly agree” with involvement in politics, and among African American mosques 70% “strongly agree.” Among all other ethnicities, over 80% “strongly agree” with political involvement. Possible explanations are that some new immigrant groups are uncomfortable with involvement and some African American mosque leaders, reflecting their experience in America, are cynical about the efficacy of political involvement.

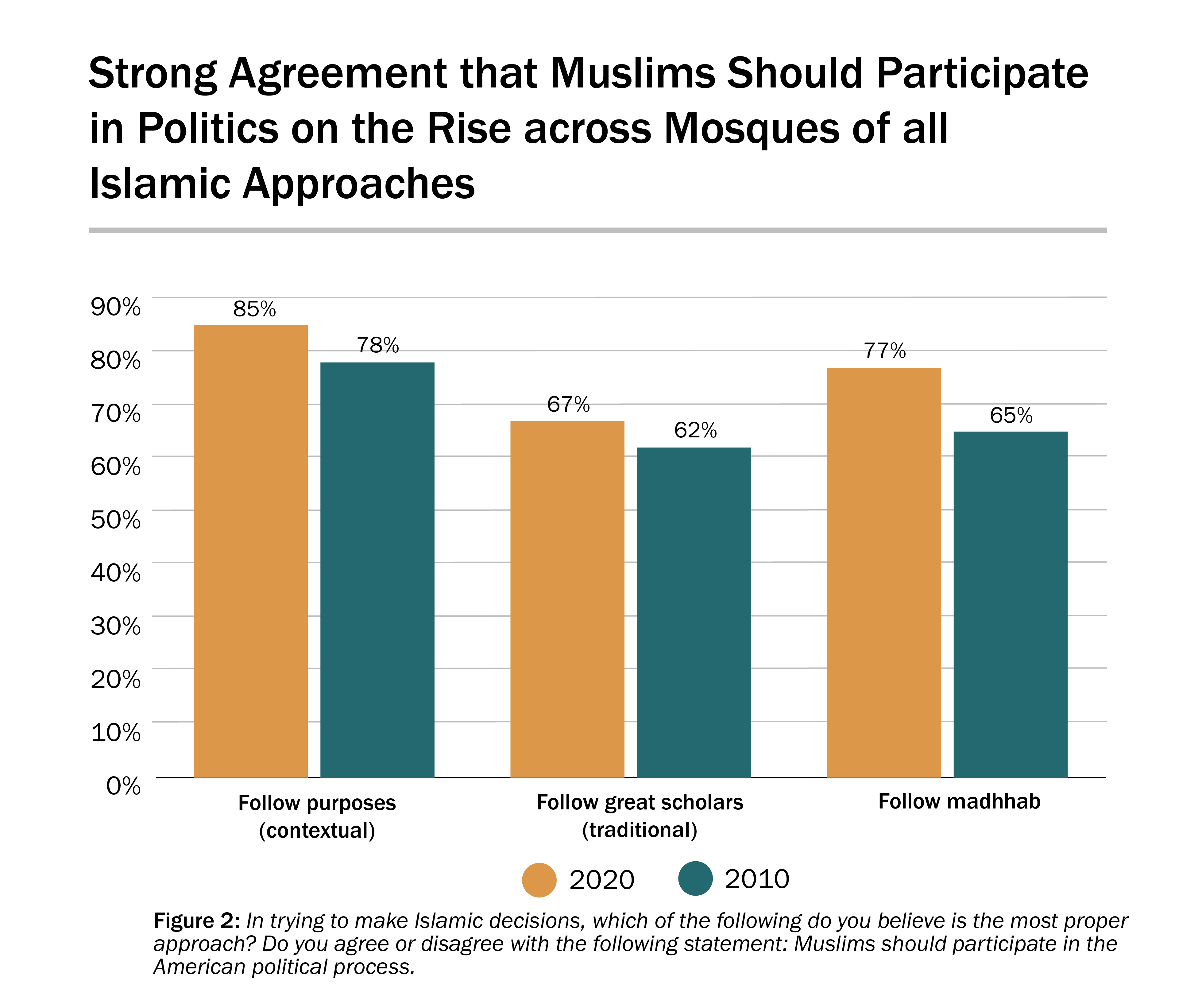

Comparing political involvement with Islamic approaches, mosque leaders who prefer the more flexible approach of looking to the purposes of Islamic law are the most enthusiastic in supporting political involvement: 85% of these mosque leaders “strongly agree” that Muslims should be involved in politics. Among mosque leaders who look to the scholars of the past, 67% of them “strongly agree” with political involvement.

The most surprising statistic is that among mosque leaders who follow a madhhab, 77% “strongly agree” with political involvement. In 2010, only 65% of mosque leaders who follow a madhhab “strongly agreed” with involvement in American politics. In 2010, 16% of mosque leaders who follow a madhhab were neutral or disagreed with political involvement, and now that figure is down to 6%. It might be expected that the more traditional madhhab mosque would be less enthusiastic about political involvement, but this seems to be no longer the case. One possible explanation is that the madhhab approach is no longer dominated by South Asian mosques and their typical Deobandi approach which has not been enthusiastic about involvement in American society. Madhhab mosques are now more represented by Turkish and Bosnian mosques, which apparently are less averse to involvement in American society.

American Society and the Question of Its Hostility and Immorality

Another two questions that attempt to gauge how mosque leaders view America asks whether they agree or disagree with the statements “American society is hostile to Islam” and “American society is immoral.”

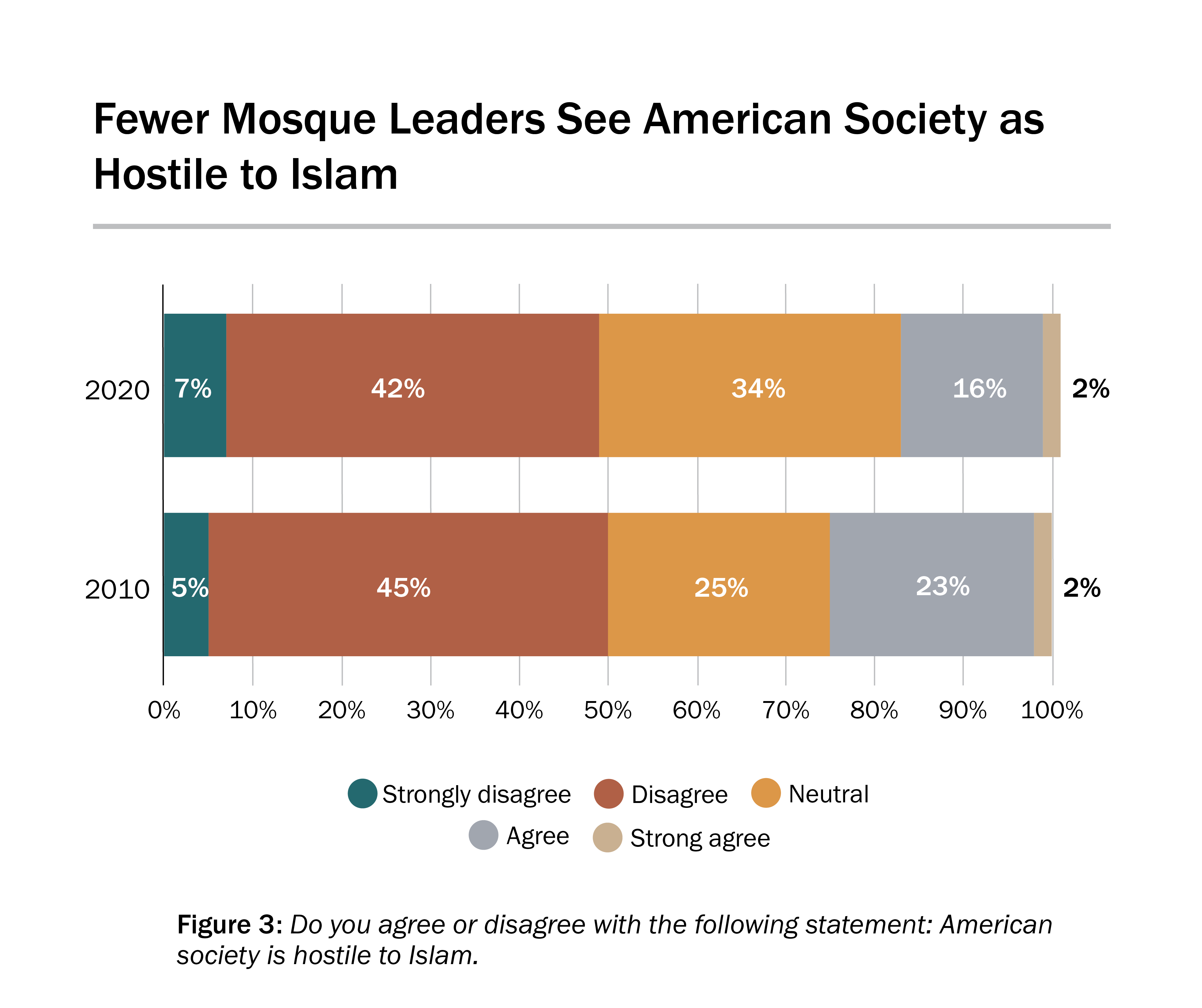

The first question measures the degree to which mosque leaders think that Americans are negative or prejudiced against Islam. Only 18% of mosque leaders agree that Americans are hostile toward Islam, indicating that the vast majority of mosque leaders feel that Muslims are accepted in America. Many mosque leaders struggled with this question, saying that while they do not view their local community as being hostile, on the national scene there is apparent hostility. As a result, many preferred the middle of being neutral or simply agreeing. There is a modest change from 2010 in that there is an increased sense of America’s acceptance of Islam: In 2010, 25% of mosques leaders agreed that America is hostile to Islam, and in 2020 only 18% agreed. The Trump years have apparently not soured mosque leaders in their overall view of America’s lack of hostility toward Islam and Muslims.

How a mosque leader responds to the question of American hostility to Islam does not affect their responses to civic and political participation. The strong endorsement of civic and political participation comes equally from leaders who feel America is hostile and those who feel America is not hostile. Both sides are persuaded to be involved.

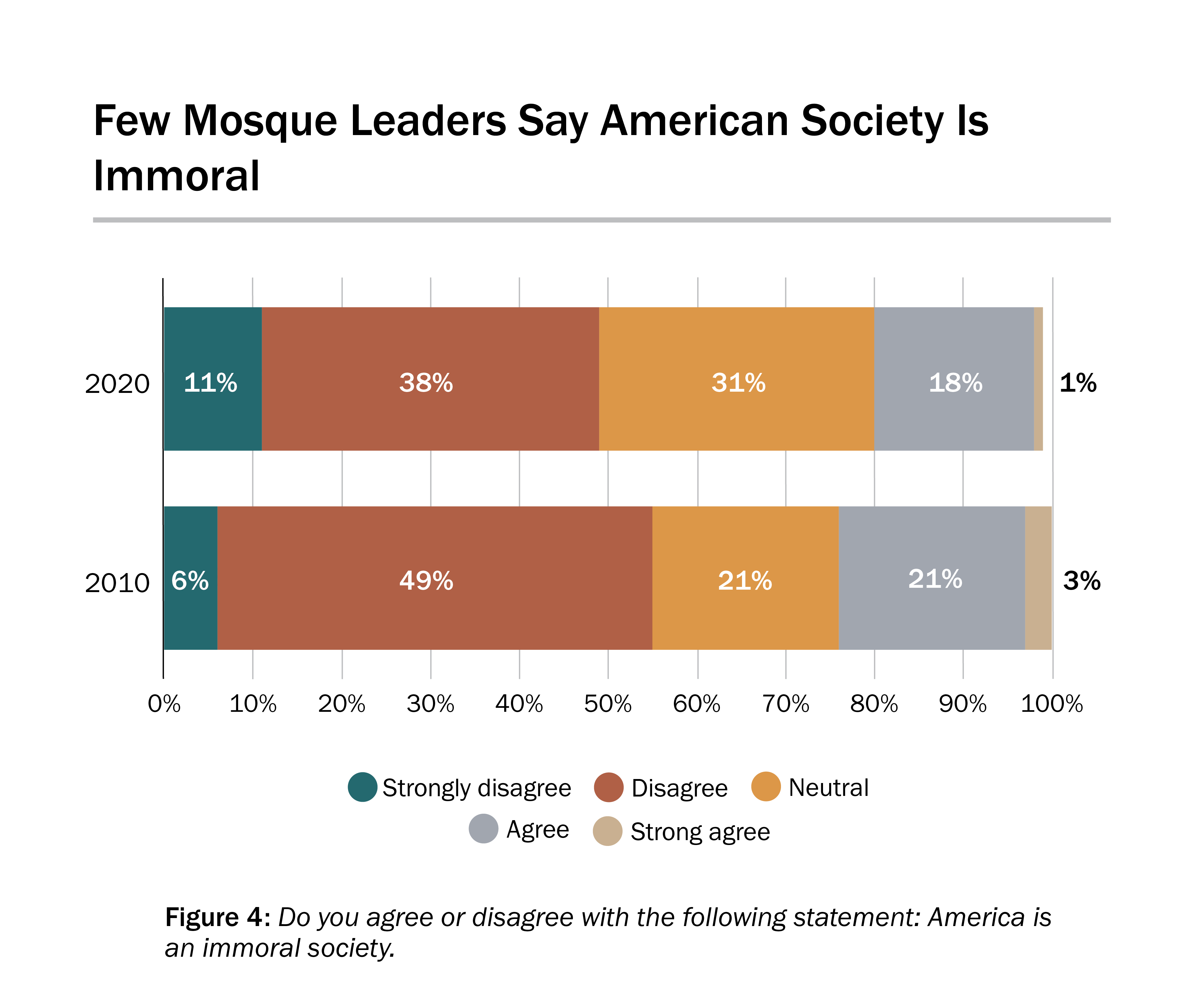

The second question measures the degree to which mosque leaders think negatively about the morals of American society. The moral values and behavior of mainstream Islam can be quite different than popular American culture. While recognizing these differences, many mosque leaders commented that the political and business culture in America is more moral (honest, fair) than in some majority Muslim countries. As with the last question, the vast majority of mosque leaders do not view American society as immoral: only 19% agree with the statement that American society is immoral as compared with 49% who disagree. There is little significant change from 2010 to 2020.

African American mosques are much more critical of American society’s morals than immigrant mosques: 53% of African American mosques agree that American society is immoral, but only 15% of immigrant mosques agree. African American Muslims are more sensitive to what they see as American immorality, influenced undoubtedly by the fact that most African American mosque leaders are converts who came to Islam due to their rejections of much of American popular and political culture.

Unlike the responses to the question of hostility, responses to the question of immorality do affect involvement in politics. Those mosques that view America as immoral are less likely to strongly agree with involvement in political participation; vice versa, those who do not view America as immoral are more likely to strongly agree with political involvement. The logical connection is that the view of America’s immorality leads some mosques to turn away from involvement in politics. This point will be discussed further in the section on the political activities of mosques.

.

MOSQUE ACTIVITIES

Worship: Daily Prayers (Salah)

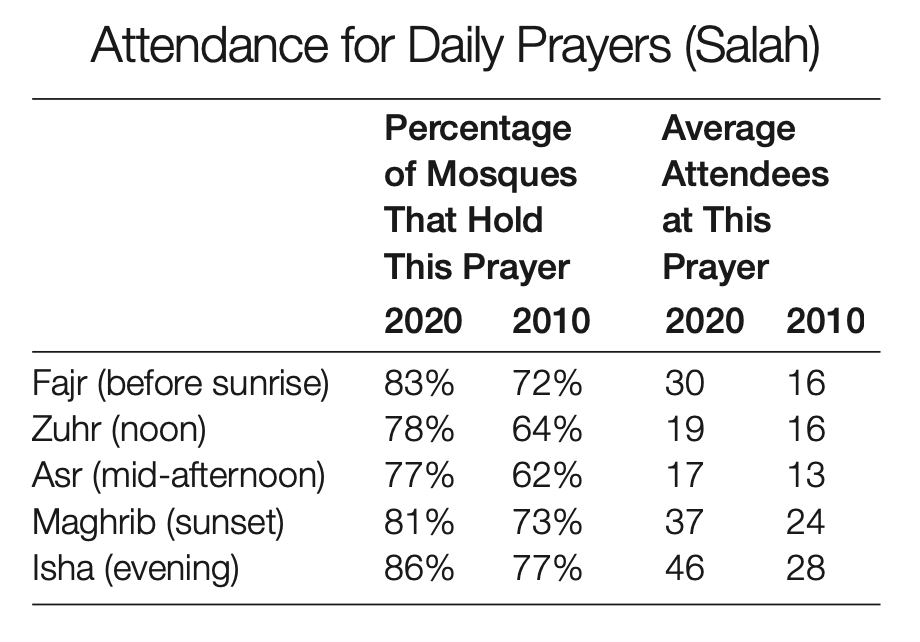

Almost three-fourths of all mosques (73%) hold all five of the ritual prayers (salah). The five prayers include Fajr (before sunrise), Zuhr (noon), Asr (mid-afternoon), Maghrib (sunset), and Isha (evening). This percentage is a significant increase from 2010 when 60% of mosques held all five prayers. One explanation is that the increased number of mosque participants in 2020 has made it easier to hold all five prayers. Only 11% of mosques do not hold any of the daily prayers. Over 80% of mosques hold the morning prayer (before sunrise), the sunset prayer, and the evening prayer—times at which most people are not working. Holding all five prayers means that American mosques are open every day and that traffic in and out of the mosques is brisk.

Language of Jum’ah Prayer (Friday Congregational Service)

Almost three-fourths of mosques (72%) use only English for the main message of the Jum’ah sermon. In 2010 that figure was 70% and in 2000 it was 53%. This is a remarkable statistic, taking into consideration that most mosques are attended by first-generation immigrants. This is another demonstration that the American mosque has adjusted well to the American environment. Altogether, 14 different languages are used. Arabic is the main language for the Jum’ah sermon in 14% of mosques. In another 3% of mosques, which are usually South Asian mosques, the official Jum’ah sermon is in Arabic, but English is used for a “bayyan” or unofficial sermon before the official sermon.

Religious Educational Programs

As in the past, the most popular religious educational programs are the Islamic study class and the weekend school for children: 83% of mosques hold some type of Islamic study class, and 76% of mosques have a weekend school for kids. There has been no change in these figures since 2010.

A more recent phenomena is the emergence of Qur’an memorization schools, which can take the form of a full-time school that meets five days a week or as an intensive after-school program that meets a few hours five days a week. The purpose of these schools is to produce youngsters who have memorized the entire Qur’an. Over one-fourth of mosques (27%) have such memorization schools.

New Muslim activities are still not common in mosques, but the Mosque Survey shows an increase in activities or classes organized for new Muslims: In 2010, 23% of mosques had new Muslim activities/classes, and in 2020 that figure increased to 36%. There has always been a recognition of the need for new Muslim activities, and now mosques are slowly beginning to address that need.

On average, mosques, which have an Islamic study class, organize three classes. These classes are often Qur’an study, Arabic, and general where talks are given.

Weekend school attendance averages 116 children, and in 2010 average attendance was 107. As might be expected, the size of a mosque is a major determining factor: only 46% of mosques with a Jum’ah attendance of 1-50 have a weekend school with an average attendance of 23. Of those mosques with Jum’ah attendance of over 100, 90% have a weekend school with average attendance in the hundreds.

Social and Group Activities

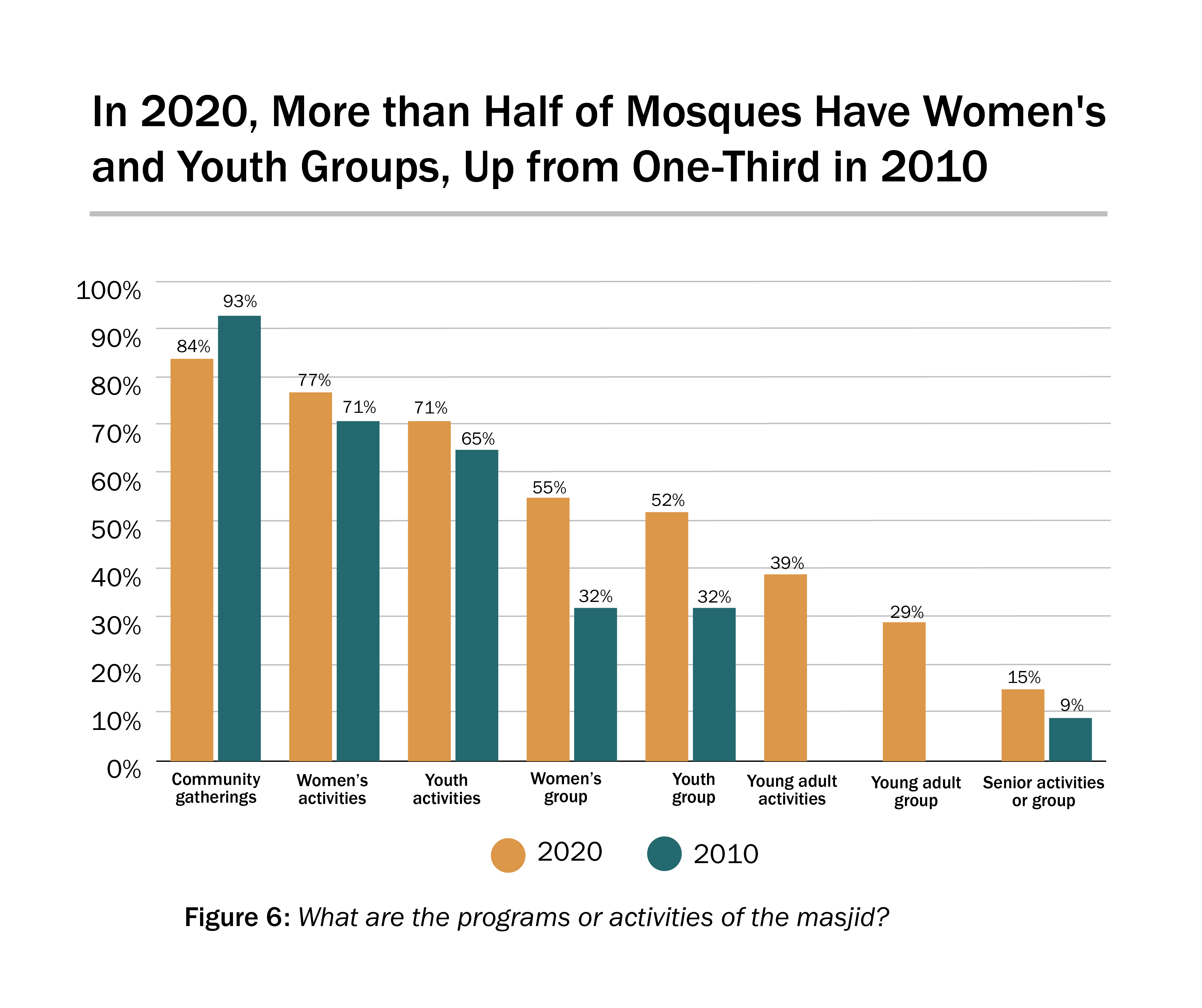

Community gatherings, which include gatherings for pot-luck dinners or to discuss issues, are the most common group activities: 84% of mosques hold such gatherings. However, the percentage of mosques that organize a community gathering decreased slightly from 93% in 2010 to 84% in 2020. This result is probably due to mosque growth, because very large mosques have difficulty in organizing community-wide gatherings for their large congregations.

Women and youth activities are the second and third most common activities. Those activities have grown slightly from 2010 to 2020. The largest increase in group activities is in the number of women’s groups and youth groups: the percentage of mosques that have a women’s group grew from 32% in 2010 to 55% in 2020, and youth groups grew from 32% in 2010 to 52% in 2020. These increases are probably due also to mosque growth because larger congregations find it easier to organize group activities.

One of the more recent concerns of mosque leaders is the lack of participation of young adults (ages 18-35). Mosques are slowly responding to this concern with more activities focused on young adults. Approximately 39% of mosques organized young adult activities in 2020, and 29% have a young adult group. This is still well behind other faith groups who are equally concerned about young adults: 66% of churches and synagogues have young adult activities (see Faith Communities Today in Sources).

The American Muslim community is slowly growing older, and mosques are starting to respond with senior activities. In 2010, only 9% of mosques had a senior program, but in 2020 that figure was up to 15%.

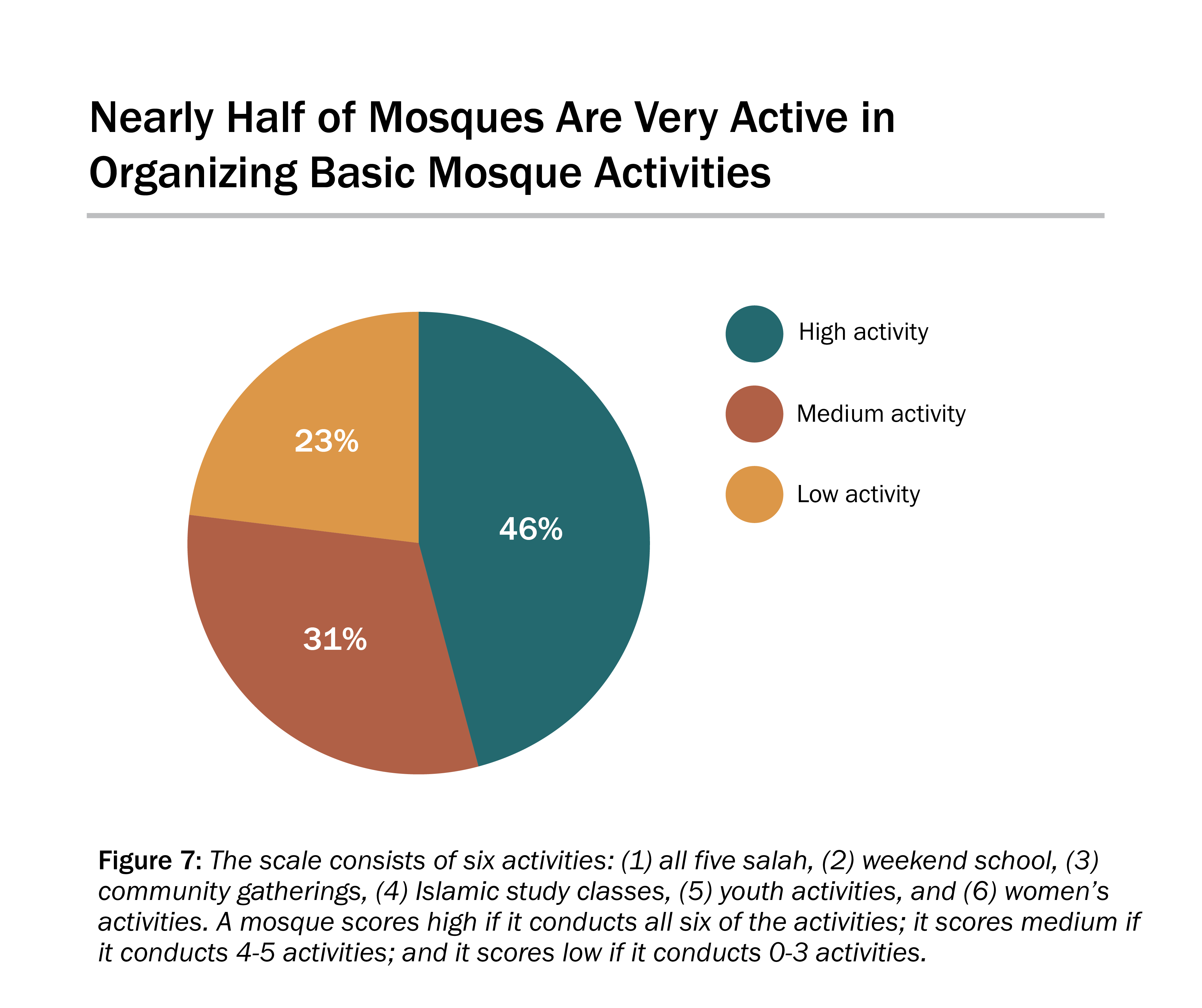

Scale for Basic Mosque Activity in the Areas of Worship, Education, and Group Activities

Worship, religious educational programs, and group activities can be viewed as the primary functions of a mosque—or, for that matter, any religious congregation. To better analyze mosques, a scale for basic mosque activity was developed. A mosque that scores high is a very active mosque and a mosque that scores low is less active. The scale consists of six activities: (1) all five salah, (2) weekend school, (3) community gatherings, (4) Islamic study classes, (5) youth activities, and (6) women activities. A mosque scores high if it conducts all six of the activities; it scores medium if it conducts 4-5 activities; and it scores low if it conducts 0-3 activities. A mosque that scores high is open every day of the week and is filled with activities that attract all of the various age groups. A mosque that scores medium is not open every day, and certain activities are not held. A mosque that scores low is not open every day and does not hold many activities that attract various age groups.

Almost half (46%) of mosques score high on the scale; only 23% score low.

These results point to the conclusion that the American mosque is not simply a place of worship as it is in the Muslim world. The American mosque has embraced the ideal that a mosque is to be a worship-community center which strives to be a nexus for all types of activities for the entire community.

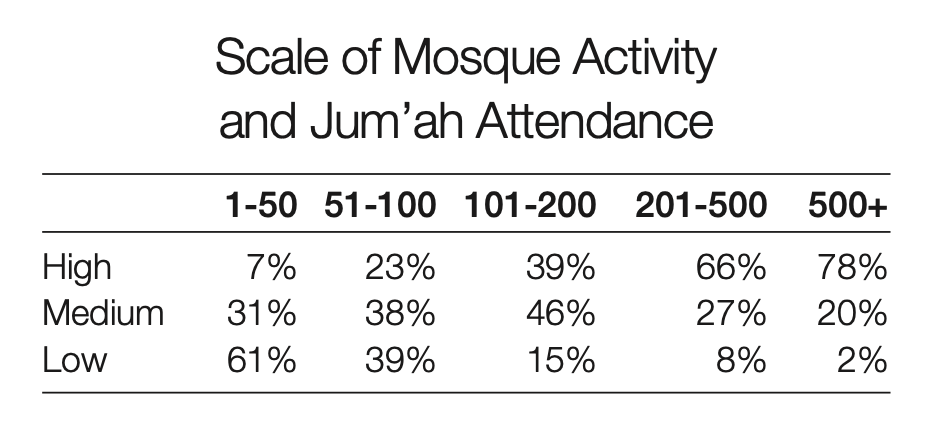

The number of mosque attendees at Jum’ah prayer is strongly associated with the level of activity: More attendees equal higher activity and the lower number of Jum’ah attendees leads to lower activity. Mosques with Jum’ah attendance over 200 typically have high scores for mosque activity. Mosques with attendance of 100 and below typically have low scores.

The presence of a full-time paid imam is also associated with high scores for mosque activity. Two-thirds (66%) of mosques with a full-time paid imam score high in mosque activity. The connection of a full-time paid imam with high scores might also be due to high Jum’ah attendance, which allows a mosque to hire a full-time imam. Nevertheless, the full-time paid imam is undoubtedly a means to a high level of mosque activity.

Mosque activity is not associated with the mosque’s Islamic approach. Whether a mosque prefers looking to the purposes, looking to the great scholars, or following a madhhab, the Islamic approach does not affect mosque activity. All of the Islamic approaches are committed to a mosque that is active in the areas of worship, education, and group activities.

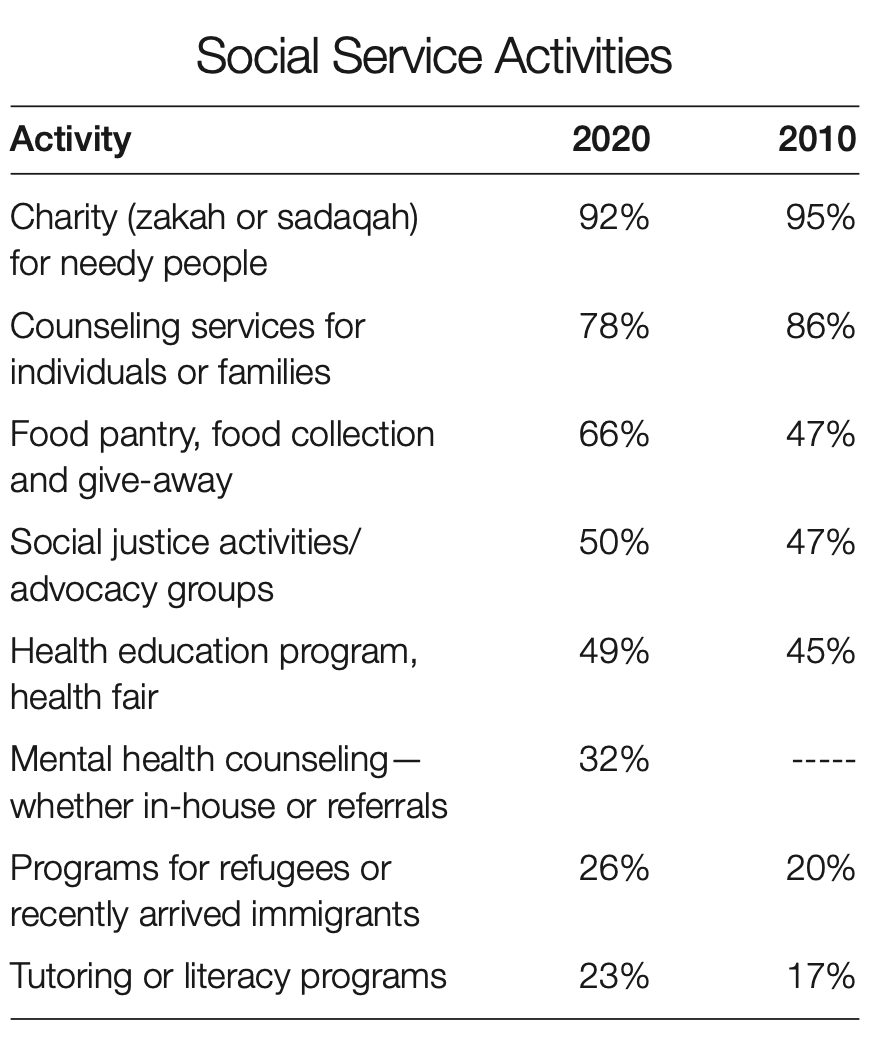

Social Service Activities

Mosques are extremely active in charity. Giving in charity (zakah or sadaqah) is a religious duty of individual Muslims, and although mosques do not receive the majority of zakah payments, they still receive a sizable amount. On average, mosques collect $40,640 for zakah, with a median amount of $15,000. Multiplying the average amount collected for zakah times the number of mosques (2,769), mosques collect and distribute $112 million in charity every year. Mosques distribute this money to the needy people and organizations in their locales that serve them.

Counseling is another service in the majority of mosques: 78% provide family and marital counseling services, which is usually the job of the imam. This is a slight decline from 86% in 2010, which is most likely due to a growing reluctance of mosques to provide counseling services by non-professional counselors and a reluctance to overburden the imam with a large workload of counseling cases.

A major increase occurred in providing a food pantry or food distribution program: in 2020, two-thirds (66%) had a food program as compared to 47% in 2010. The Qur’an commands Muslims to feed the hungry, so this type of program has a natural appeal to the Muslim mind.

A new question in the 2020 survey focused on mental health counseling, which is a growing concern in the Muslim community. Almost one-third of mosques (32%) provide in-house counseling or referrals for mental health counseling. In large cities, Muslim mental health clinics are growing in number, and mosques are taking advantage of their services.

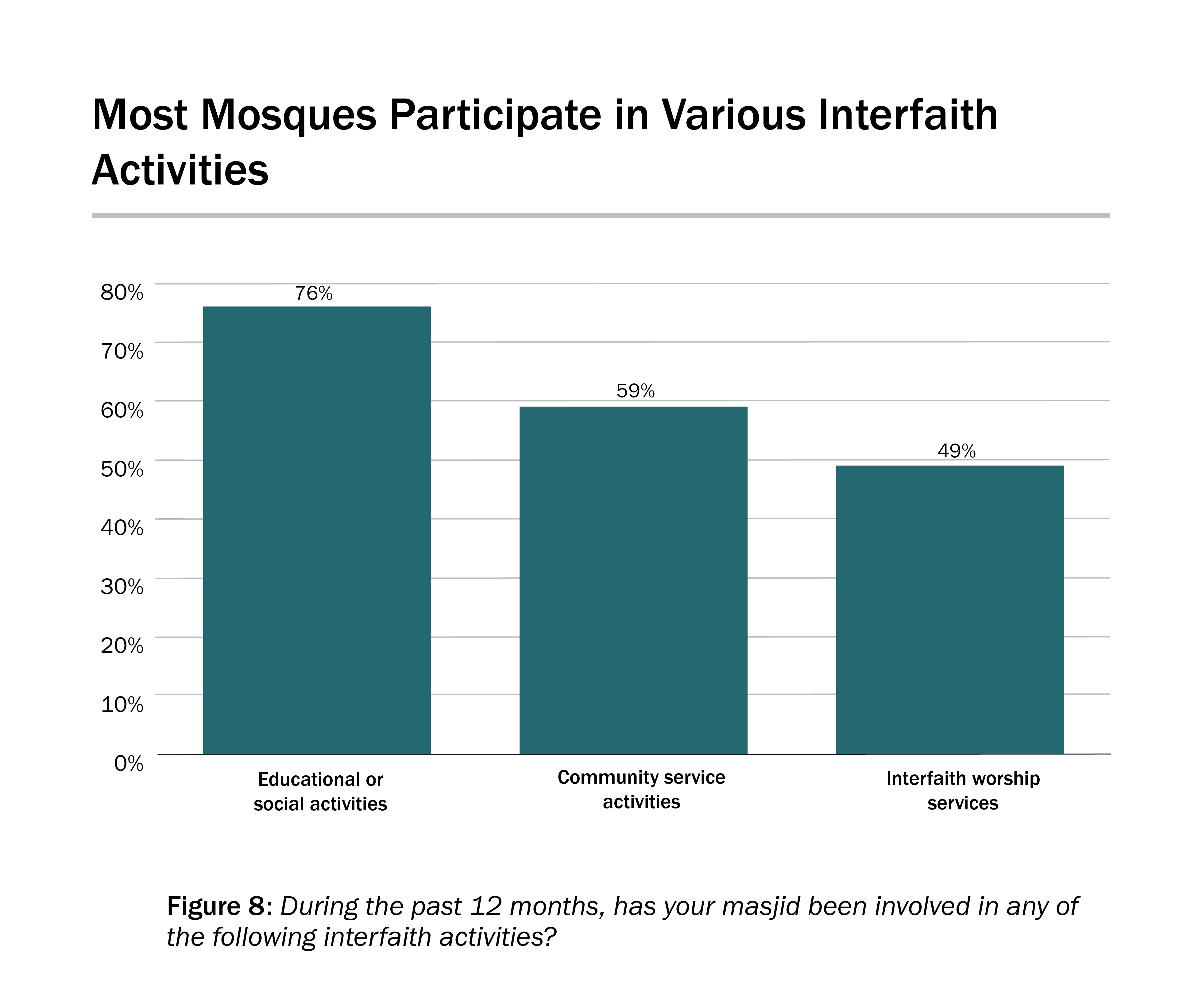

Interfaith Activities

Mosques are very much involved in interfaith activities. Overall, 78% of mosques are involved in at least one of the interfaith activities listed in the chart below. Involvement in interfaith activities has not changed since 2010, but there is a marked change from 2000 when 66% participated in some type of interfaith activity.

Those mosques which follow the more flexible approach of looking to the purposes of the law and modern circumstances tend to participate more in interfaith activities than mosques that follow a madhhab (classical legal school) or the great scholars of the past. This difference appears more starkly in participation in interfaith worship services: only 27% of mosques that follow the great scholars of the past participate in interfaith worship services; 40% of mosques that follow a madhhab participate, compared to 66% of mosques that follow a more flexible approach.

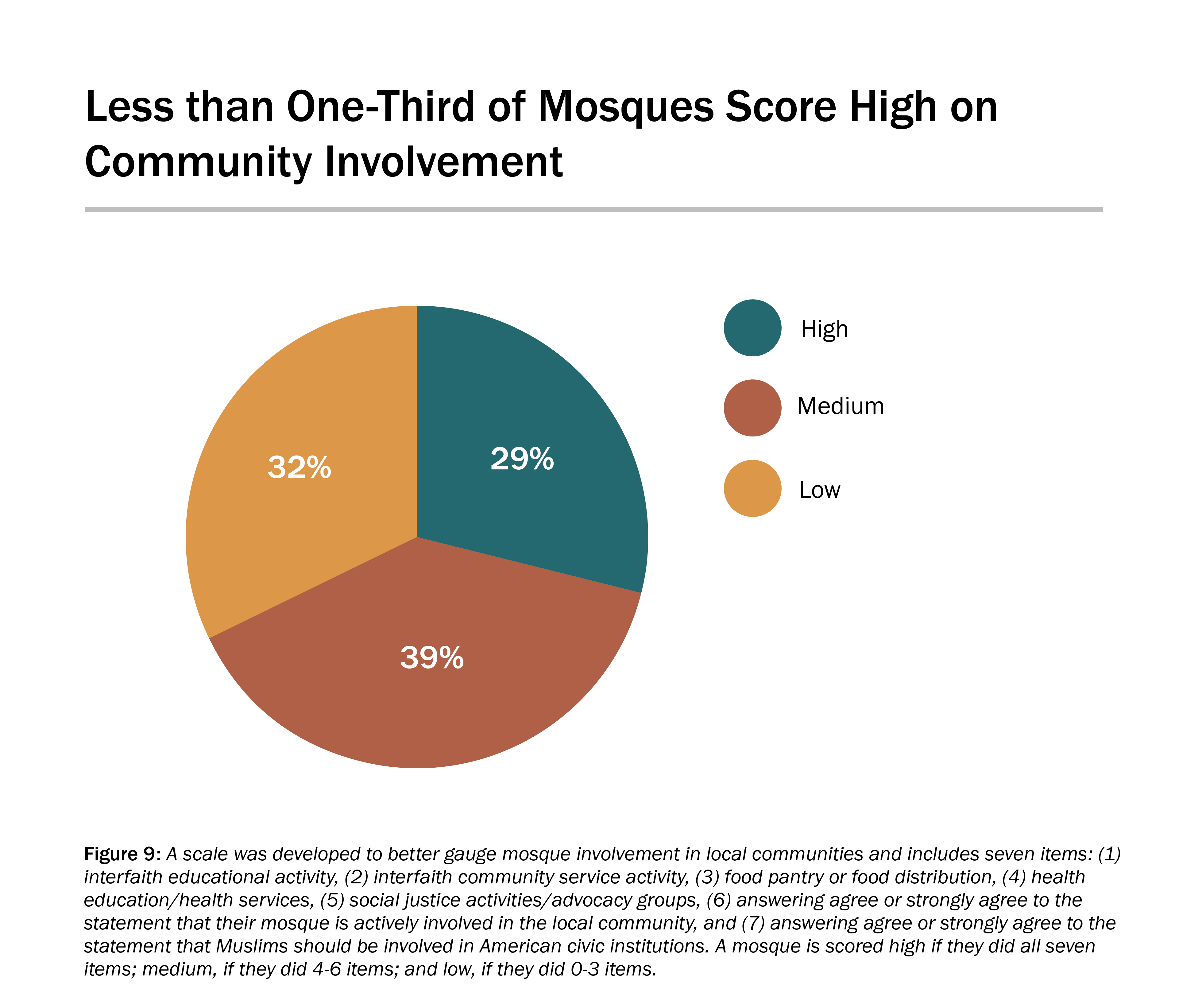

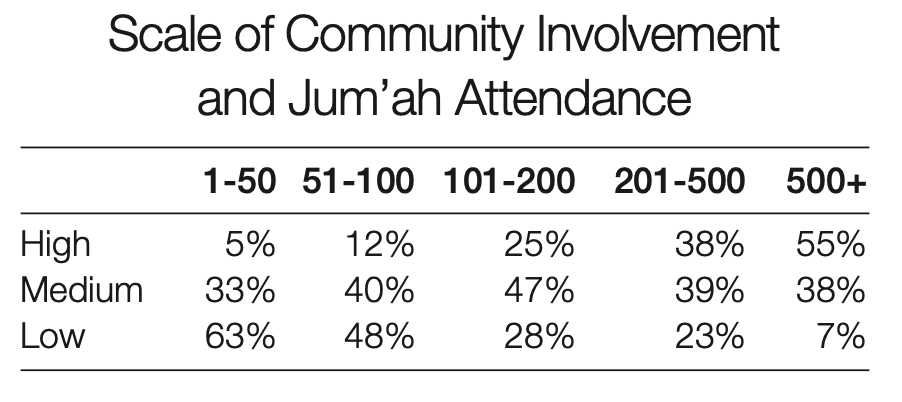

Scale for Community Involvement

A scale was developed to better gauge mosque involvement in local communities and includes seven items: (1) interfaith educational activity, (2) interfaith community service activity, (3) food pantry or food distribution, (4) health education/health services, (5) social justice activities/advocacy groups, (6) answering agree or strongly agree to the statement that their mosque is actively involved in the local community, and (7) answering agree or strongly agree to the statement that Muslims should be involved in American civic institutions. A mosque is scored high if they did all seven items; medium, if they did 4-6 items; and low, if they did 0-3 items.

Only 29% of mosques score high in the community involvement scale. In comparison, 46% of mosques scored high regarding mosque worship, educational programs, and group activities. Overall, mosques give priority to the basic activities of a mosque and a lower priority to community involvement.

The size of Jum’ah attendance is again strongly associated with community involvement. The larger the Jum’ah attendance, the higher the level of community involvement.

The apparent connection between community involvement and Jum’ah attendance is simply that the increased number of people equals increased human and financial resources, which can be utilized to organize more community involvement activities. Mosques, as demonstrated in their embrace of civic engagement, are already predisposed to community involvement and, therefore, are willing to use extra human resources toward that end.

However, mosque attendance is relatively high; therefore, mosques should do much better in organizing community involvement programs. For example, one would expect that a mosque with 201-500 Jum’ah attendees would have greater than 38% scoring high on community development. If it is assumed that mosques are willing to be involved in their local communities, the problem must lie in the lack of volunteers and staff. Lack of staff is evident in the statistic that two-thirds of mosques with 201-500 Jum’ah attendance have zero or one full-time staff. This is clearly an insufficient number to support all the varied mosque activities. The lack of staff means that the burden falls on volunteers, and the large number of attendees is not translating into enough volunteers.

The level of community involvement is also affected by Islamic approaches. Mosques with the flexible approach of looking to purposes of foundational sources tend to score higher in community involvement than the other approaches: 37% of mosques that look to the purposes score high in community involvement as compared to 22% of mosques that look to the great scholars of the past and 17% of mosques that follow one of the traditional madhhabs.

As with mosque activity, a mosque with a full-time paid imam scores higher in community involvement than a mosque with a part-time paid imam, a volunteer imam, or no imam. Looking more closely at full-time paid imams, a mosque with a full-time paid, American-born imam scores higher in community involvement than a mosque with a foreign-born imam. An American-born imam is undoubtedly more familiar and more comfortable with community involvement than an imam born outside America.

Community involvement is not affected by whether a mosque leader feels that America is immoral or whether America is hostile to Muslims. This demonstrates that the view of America’s immorality or hostility does not lead to an isolationist or antagonistic posture toward involvement in American society.

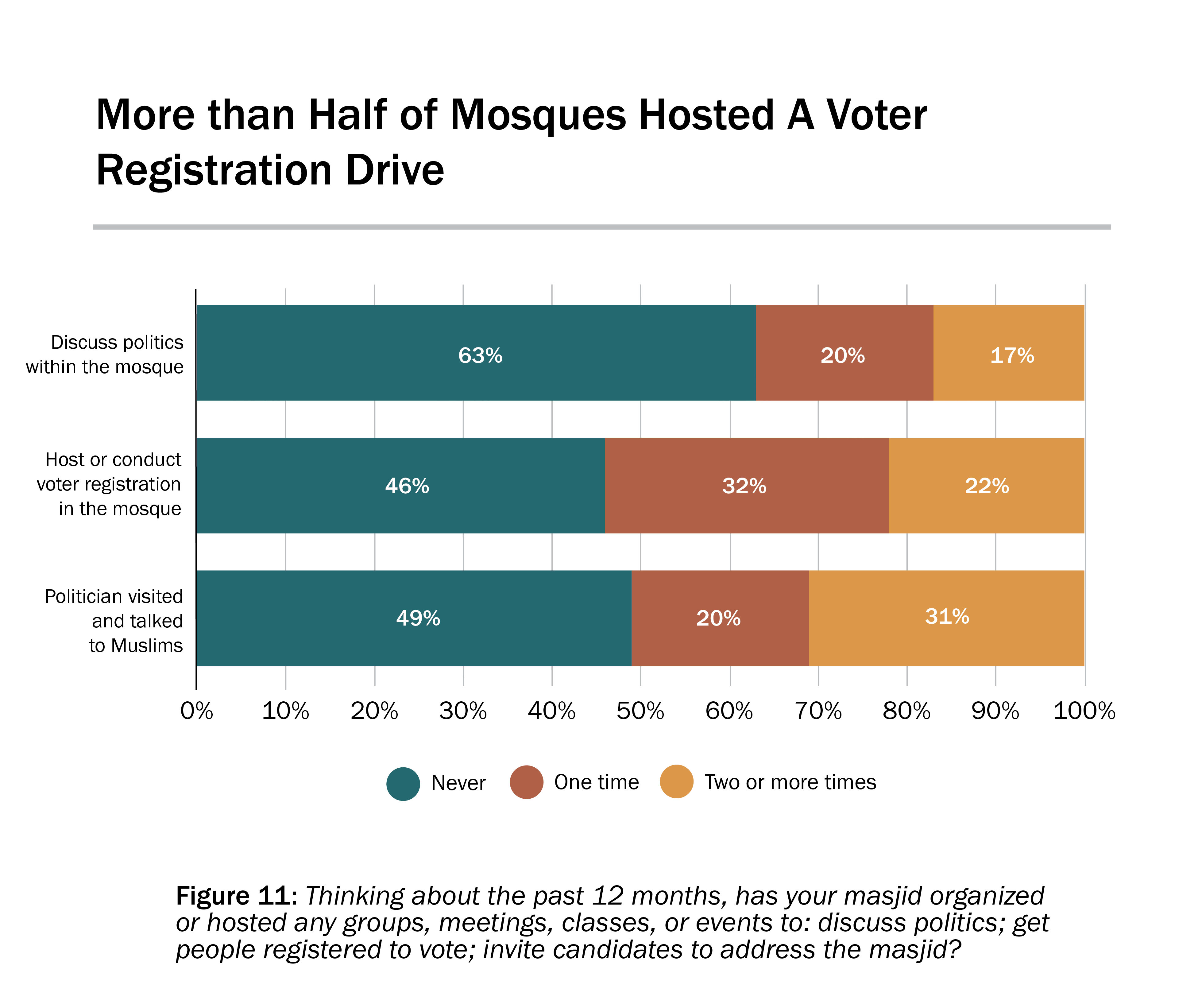

Political Activities

Mosque leaders endorse the idea that Muslims should participate in American politics, but mosques have an uneven record of getting involved as an institution. Only 37% of mosques had within the last 12 months held a meeting, class, or event to discuss politics. Many mosque leaders responded that American law does not allow them to be involved in politics. Of course, American law allows religious institutions to discuss politics, but mosque leaders are most probably expressing a wariness of possibly entangling themselves with the government.

In 2020, over half of mosques (54%) hosted or conducted voter registration in the mosque. This figure is an increase from 2010, when 48% of mosques held a voter registration drive.

A somewhat surprising figure is that 51% of mosques hosted a politician’s visit and talk. Mosque leaders often expressed pride in hosting a politician as a means of exposing important people to the Muslim community. Thus, the event is perceived not so much as a political event but as an educational opportunity.

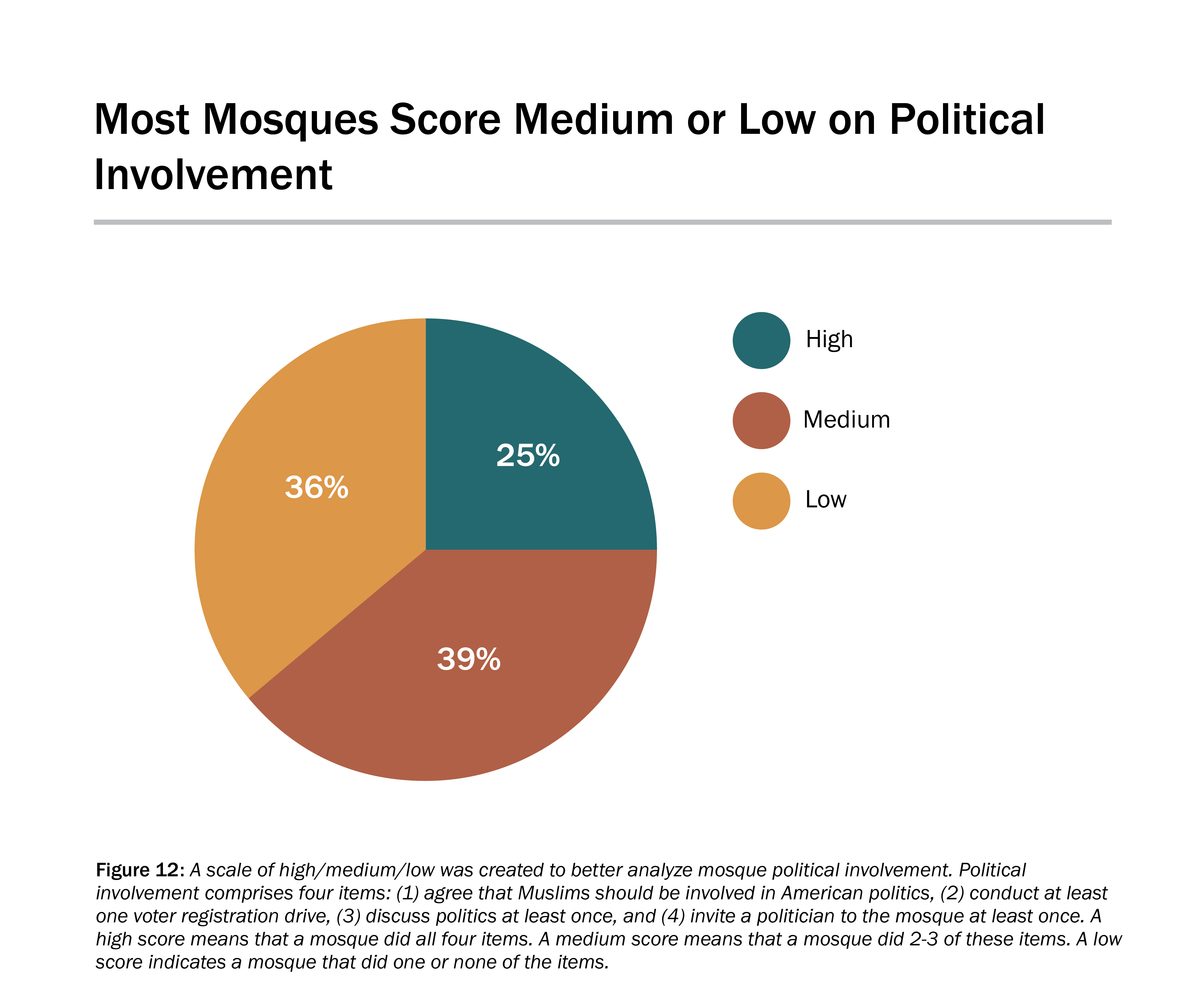

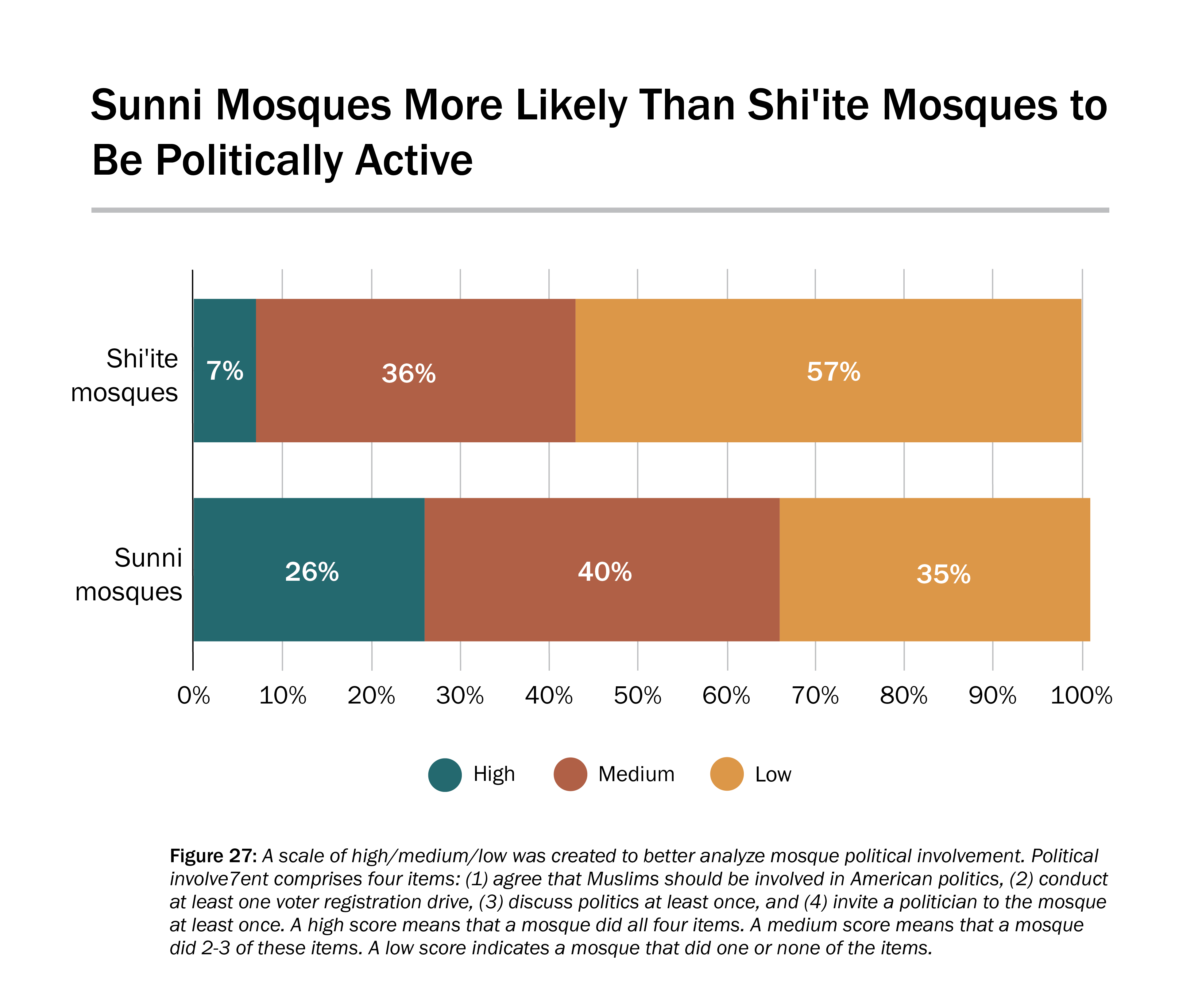

Scale for Political Involvement

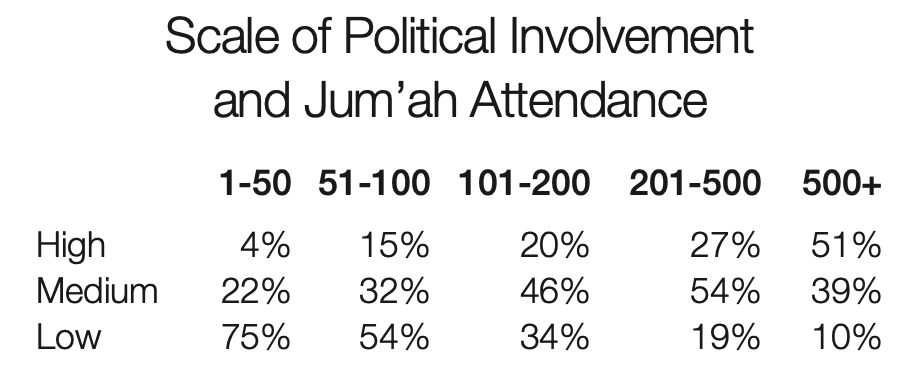

A scale of high/medium/low was created to better analyze mosque political involvement. Political involvement comprises four items: (1) agree that Muslims should be involved in American politics, (2) conduct at least one voter registration drive, (3) discuss politics at least once, and (4) invite a politician to the mosque at least once. A high score means that a mosque did all four items. A medium score means that a mosque did 2-3 of these items. A low score indicates a mosque that did one or none of the items.

Only one-fourth (25%) of mosques score high on the scale of political involvement; 39% score medium and 36% score low. These scores are lower than community involvement, showing that mosques consider political involvement a lower priority.

As with basic mosque activity and community involvement, Jum’ah attendance has a great effect on political involvement. The larger the number of Jum’ah attendees, the higher the score for political involvement.

Islamic approach is also associated with political involvement. As with community involvement, mosques which look to purposes score higher in political involvement than mosques that adopt the other approaches.

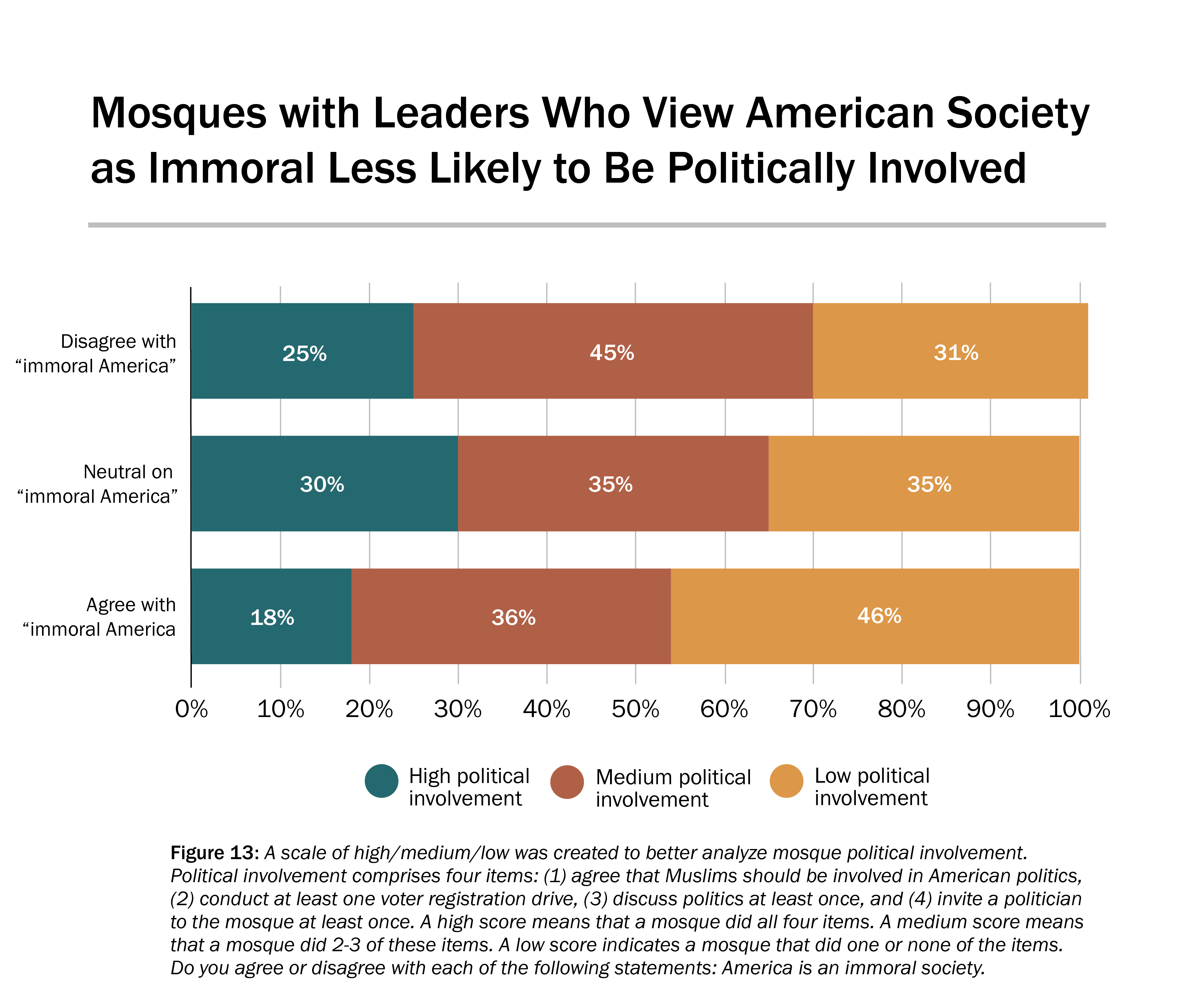

With community involvement, there was no correlation with how a mosque leader responded to the question of whether they thought America was hostile to Islam or whether they thought American society was immoral. With political involvement, there is no correlation with whether they view America as being hostile to Islam, but there is a slight correlation with the question of immorality. Only 18% of mosques that agree that American society is immoral score high as opposed to 25% who disagree and 30% who are neutral in the view of America’s immorality.

This closer correlation between viewing American society as immoral and lower scores in political involvement might be attributed to the oft-discussed question of involvement with organizations that espouse views that are contrary to Islamic mainstream views such as prohibition of abortion (although the Islamic view is more flexible than the Catholic view) and rejection of same-sex marriage.

Full-Time Islamic Schools

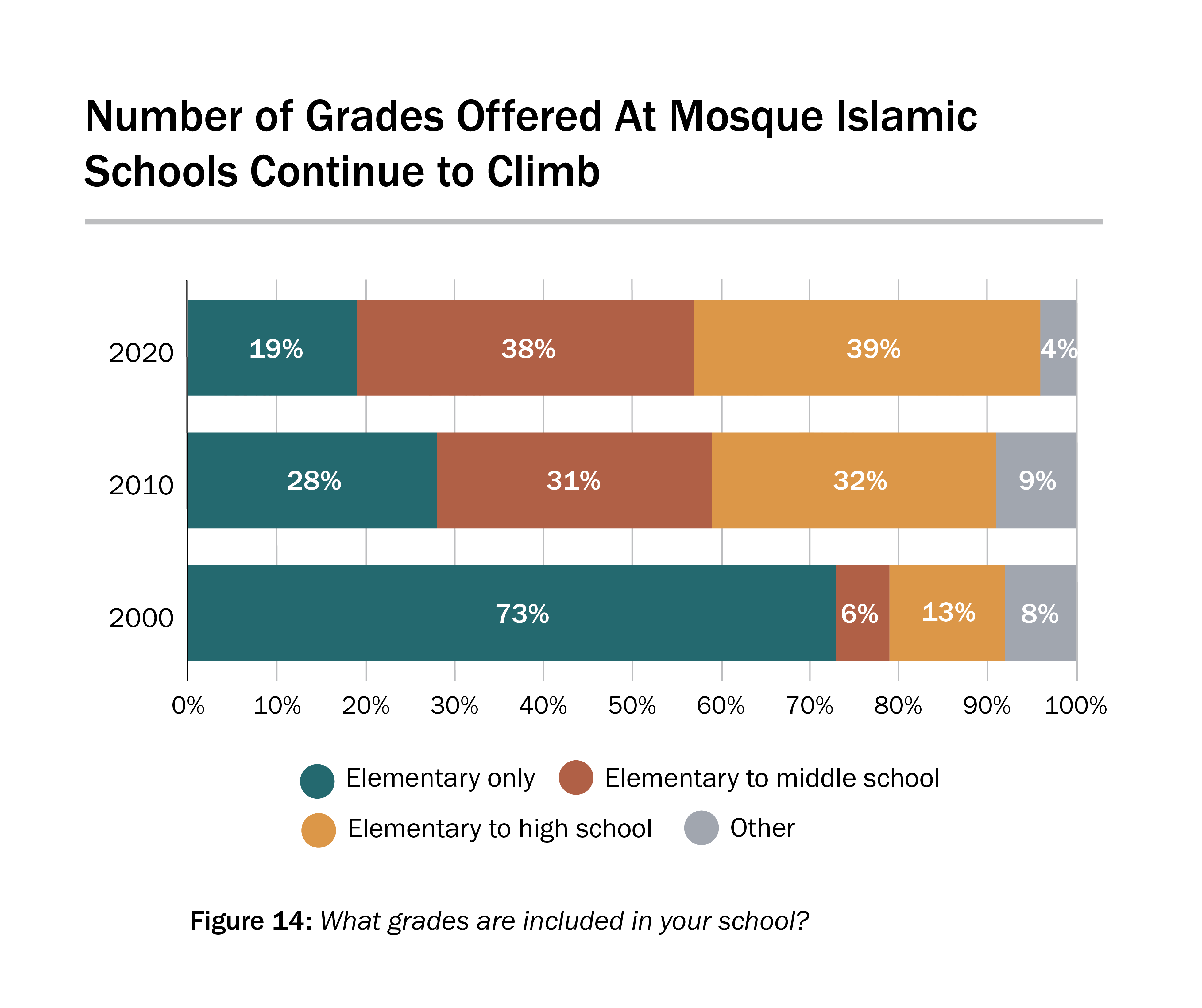

The percentage of mosques that operate or are associated with a full-time Islamic school has remained the same since 2010: In 2020 18% of mosques had a full-time Islamic school; in 2010 the figure was 19%. However, these percentages mean that the total number of Islamic schools have increased: in 2010, 19% represent 400 Islamic schools, and 18% in 2020 represent 498 schools—a 25% increase.

Islamic schools also increased in number of students: In 2010, the average number of students was 180, and in 2020 the average was 207. Islamic schools also grew in the number of grades offered. In 2020, 77% of all Islamic schools were either elementary to middle or elementary to high school. Islamic elementary-only schools decreased from 73% in 2000 to 28% in 2010; in 2020, only 19% of Islamic schools covered solely elementary grades.

.

Mosque Mission, Identity, and Vitality

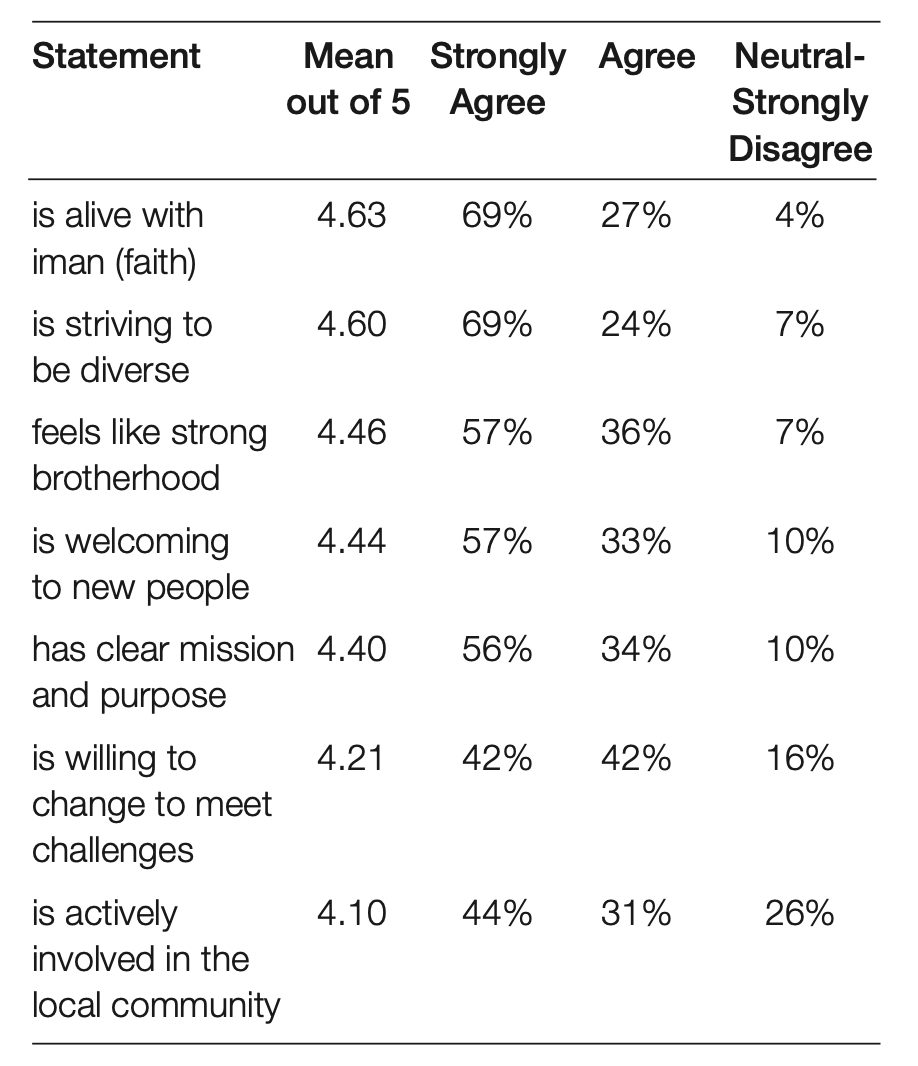

To better understand mosque leaders’ self-perception of their mosques in terms of mission, identity, and vitality, a series of statements were given to them to agree or disagree. Each statement began with “Our masjid:”

These scores are relatively high, which means that mosque leaders have positive views of their mosques.

Jum’ah attendance growth of 10% or more is associated with high scores for the following responses. “My mosque:”

-

- “has a clear mission and purpose”

- “is willing to change to meet new challenges”

- “feels spiritually alive with iman”

- “is actively involved in the local community”

This means that the mosques scoring high in agreement that their mosque realizes these aspects also score high in the increase of their Jum’ah attendance. The strongest association is with clear mission and purpose. So, those mosques with a stronger sense of clear mission and purpose achieve the highest growth rate.

There is no association of growth in Jum’ah attendance of 10% or more with those mosques responding that their mosque “is striving to be diverse,” “is good at welcoming new people into the mosque,” and “feels like a strong brotherhood.” This means that the responses to these statements have no effect on whether a mosque is growing or not growing. The inference is that all mosques have the perception that they are living up to the aspirational Islamic ideals of a diverse, welcoming, and strong brotherhood—but are they really living up to those ideals?

This pattern holds true for other aspects of mosque activities. Thus, mosques that score high in basic mosque activities, community involvement, and political involvement also score high in agreement with the four aforementioned: clear mission and purpose, willingness to change, spiritually alive, and involvement in the local community.

.

Women and the Mosque

The position and role of women in the American mosque is one of the most contentious issues within the America Muslim community. The inherited culture from some countries and some interpretations of the inherited intellectual tradition are that women have a limited place in the mosque. The American Muslim community in general never accepted the idea that women should be excluded from the mosque, but many mosques never embraced the active involvement of women.

In the past decade, there have been efforts to make mosques more welcoming to women. Studies have been conducted, fatwas (Islamic legal opinions) and collective statements published, videos produced, and speeches given. There was a clear hope that the 2020 US Mosque Survey would show some progress in regard to women in the American mosque. The results are mixed: There has been some progress but little change.

Use of Divider in the Mosque

The central debate about women in the mosque is the issue of whether women should pray in the same prayer space as men or behind some form of divider or in another room. Those mosques that offer a choice for women to pray in the same prayer space as men or behind a barrier were coded as mosques that did not use a divider. A few mosques (5%) have a mezzanine area for women, and these mosques were coded as having a divider. Mezzanines were installed in many purpose-built mosques as a compromise to give women in the mezzanine the ability to see the imam below who is giving the sermon or leading the prayer. However, the compromise is not very satisfactory because only the first row in the mezzanine can see the imam, and when there is a class or discussion in the prayer area it is very difficult for women to participate.

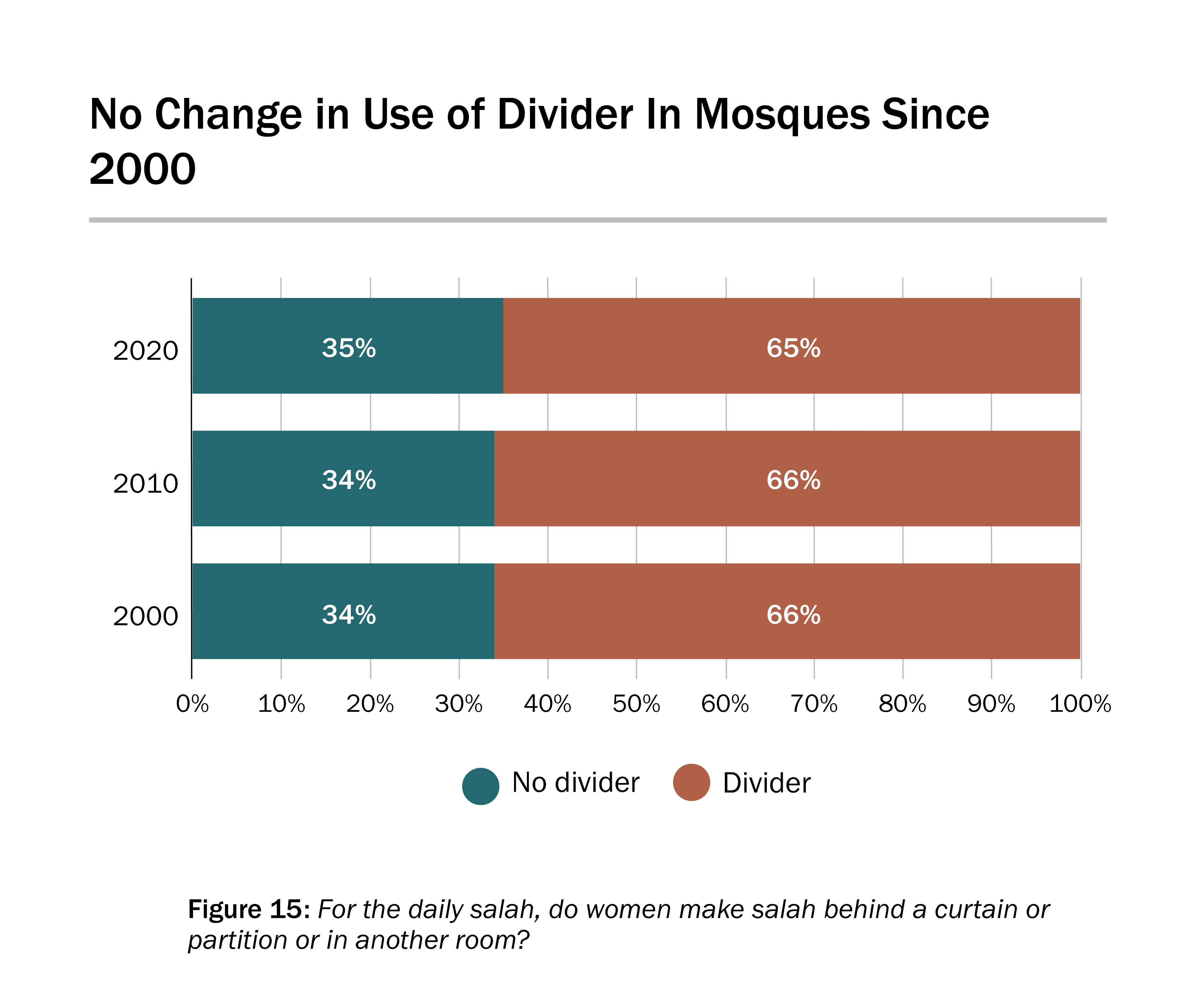

The 2020 Mosque Survey shows that no change has occurred in the percentage of mosques without a divider. The percentage of mosques with a divider has remained steady since 2000 at two-thirds, and the percentage of mosques that do not have a divider is still one-third. The issue has been raised and the discussion has been initiated, but the culture of mosques regarding dividers has remained unchanged.

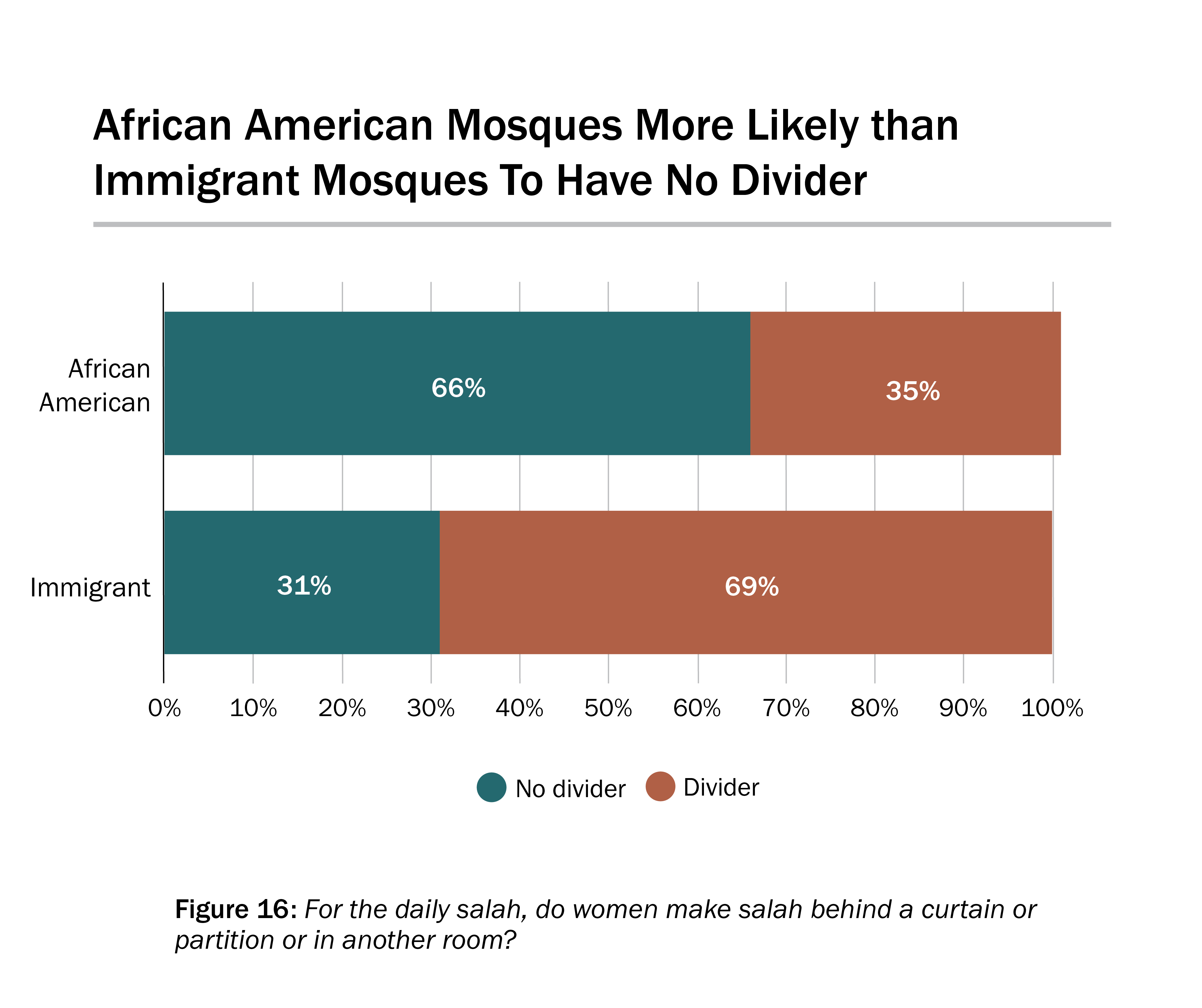

African American mosques have the highest percentage of mosques with no divider: Two-thirds of African American mosques (66%) have no barrier as compared to 31% of immigrant mosques that do not use a divider.

Clearly, the traditions from overseas where women are often marginalized in mosques have influenced the mindset and practice of Muslims who have immigrated to America.

The effect of the American experience vs. cultural heritage from overseas can be seen in the statistic that full-time paid imams who are American born are much more likely to lead mosques with no divider: 50% of mosques with a full-time paid, American-born imam do not have a divider as compared to 31% of mosques with a full-time paid foreign-born imam. Undoubtedly, this is partly the effect of the American-born imam and the effect of a mosque leadership that prefers an American-born imam. In other words, these mosques were probably already leaning away from duplicating traditions from overseas, which was what led them to hire an American-born imam.

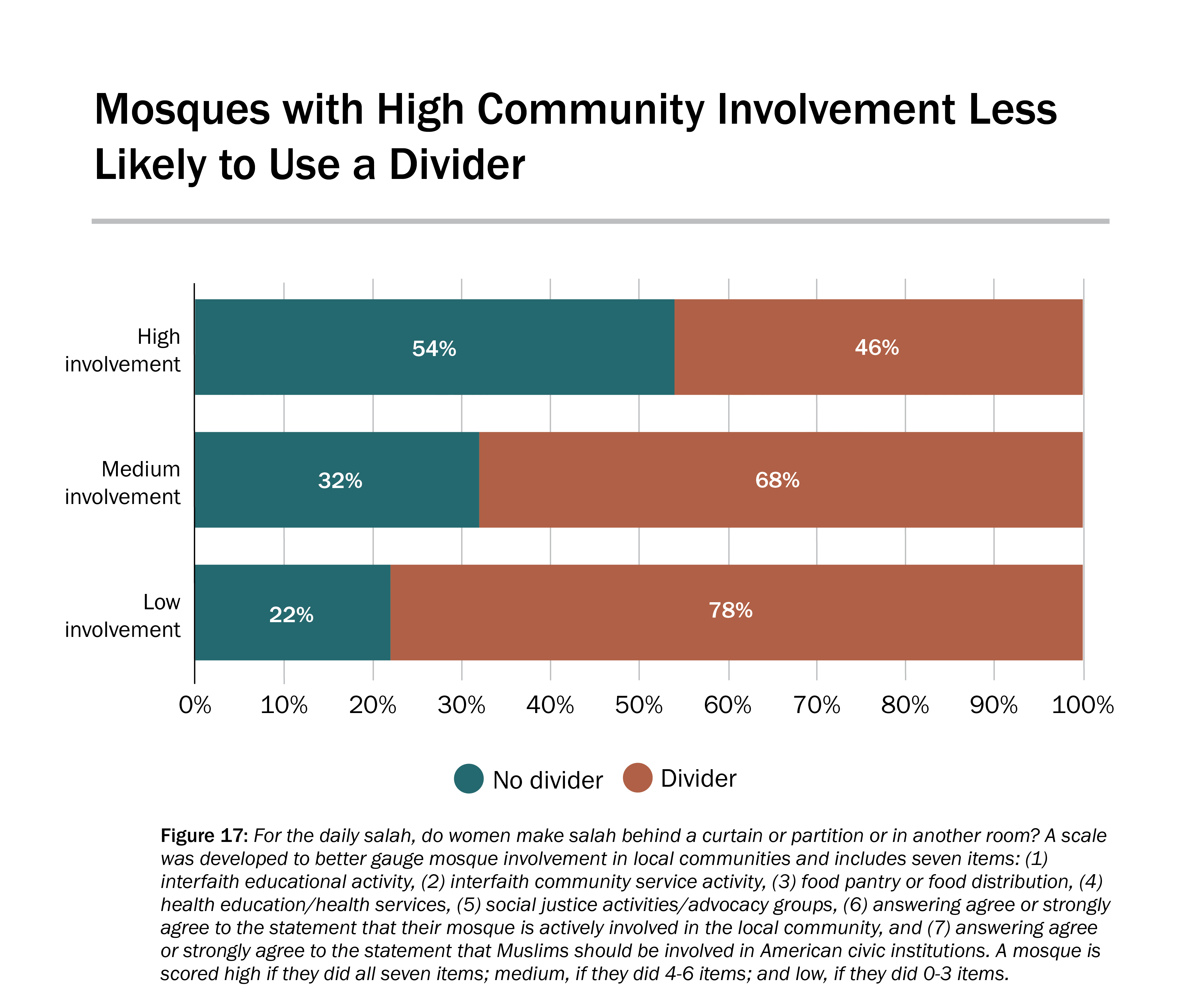

Another strong correlation is with community and political involvement. Those mosques that are actively involved in their local communities and highly politically involved are more likely to have no divider in the mosque. More than half of mosques (54%) that score high in both community and political involvement do not have dividers. Only 22% of mosques with low community involvement have no dividers in their mosques.

The connection between greater involvement and no divider seems to manifest a mindset which embraces involvement in American society and the American cultural norm that women should not be marginalized.

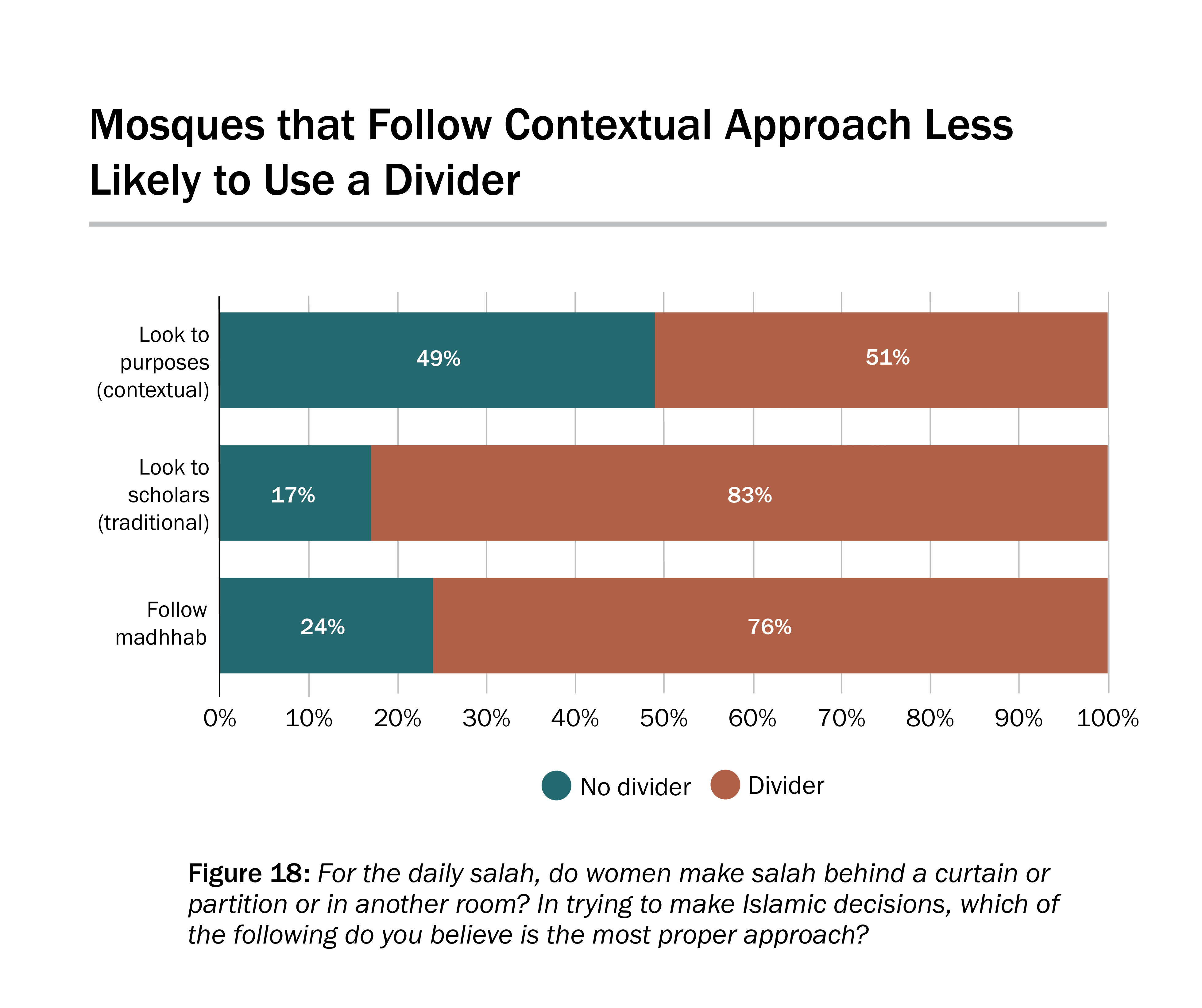

Islamic approach is another variable associated with whether a mosque has a divider or not. Those mosques that prefer the more flexible approach of looking to the purposes of Islamic law are much more likely to have no divider than the other approaches. Almost half (49%) of mosques that look to purposes have no divider. In comparison, only 17% of mosques that look to the great scholars of the past and 24% of mosques that follow a madhhab have no dividers in their mosques. Even though a higher percentage of mosques that look to purposes do not have a divider, still those mosques are evenly split between having a divider (51%) and not having a divider (49%). Obviously, even purpose-oriented mosques do not have a clear consensus and commitment to not having a divider.

The intellectual heritage of the great scholars and madhhabs is almost completely against women’s presence in the mosque or in leadership roles. Somewhat ironically, the mosque of the Prophet Muhammad did not have a barrier; in fact, he gave explicit instructions to not exclude women from the mosque. However, a century after him, a consensus developed among scholars that men disliked women’s presence in the mosque and dividers went up. Scholars who look to the purposes argue the more “conservative” approach of sticking to the practice of Prophet Muhammad.

Whether or not a mosque has a divider is not connected to mosque size, location, budget, or high scores in mission, identity, and vitality.

Women’s Participation on Mosque Boards

One positive note for women’s involvement in the mosque is the increased percentage of mosques with women on their boards. Over two-thirds of mosques (67%) have women serving on their mosque boards as compared to 59% in 2010 and 50% in 2000.

The argument that women should not serve on governing bodies of Muslim organizations has clearly been defeated: Only 7% of mosques still uphold that argument, down from 31% in 2000.

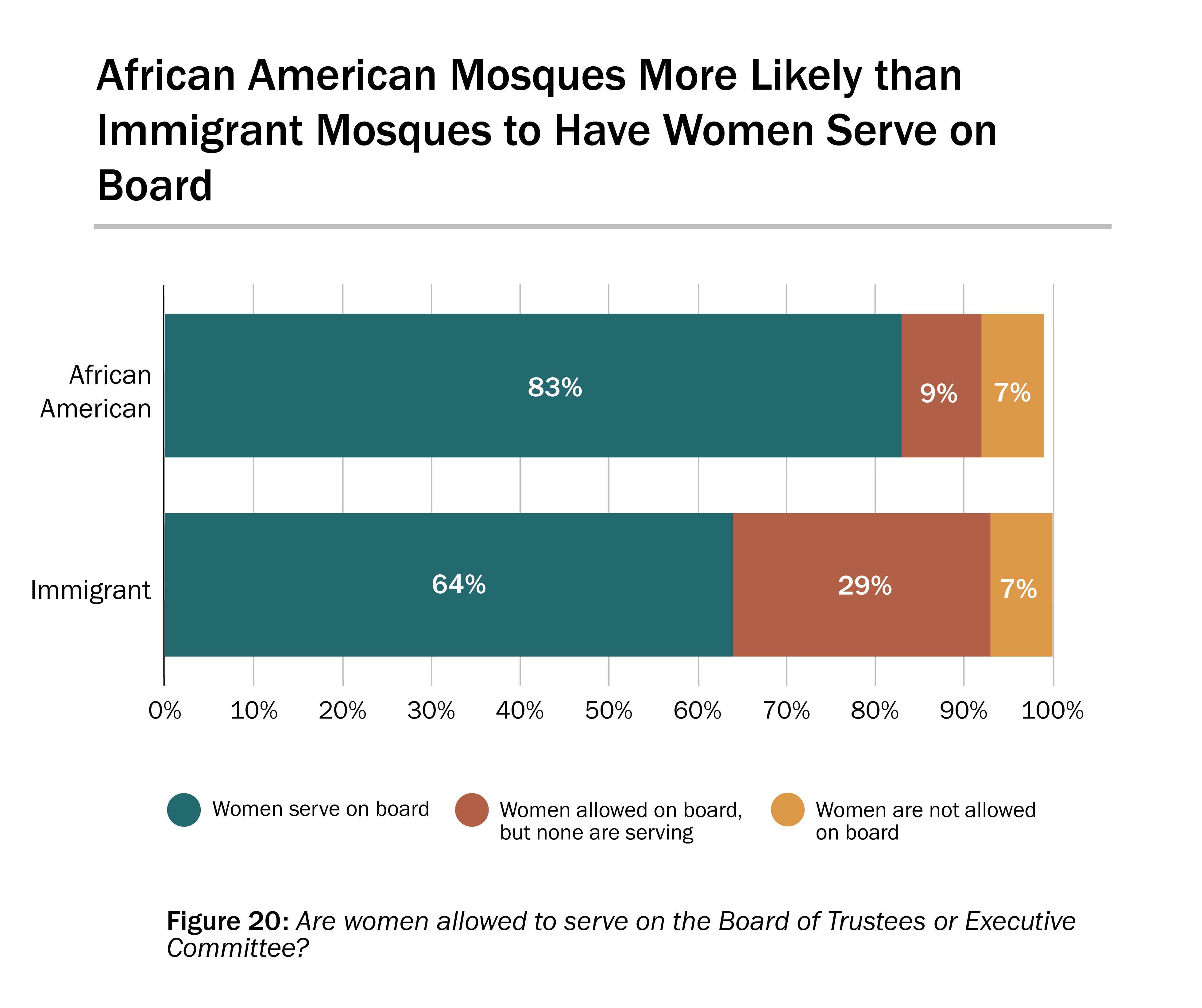

African American mosques have a much higher percentage of women on their boards: 83% have women serving on their boards.

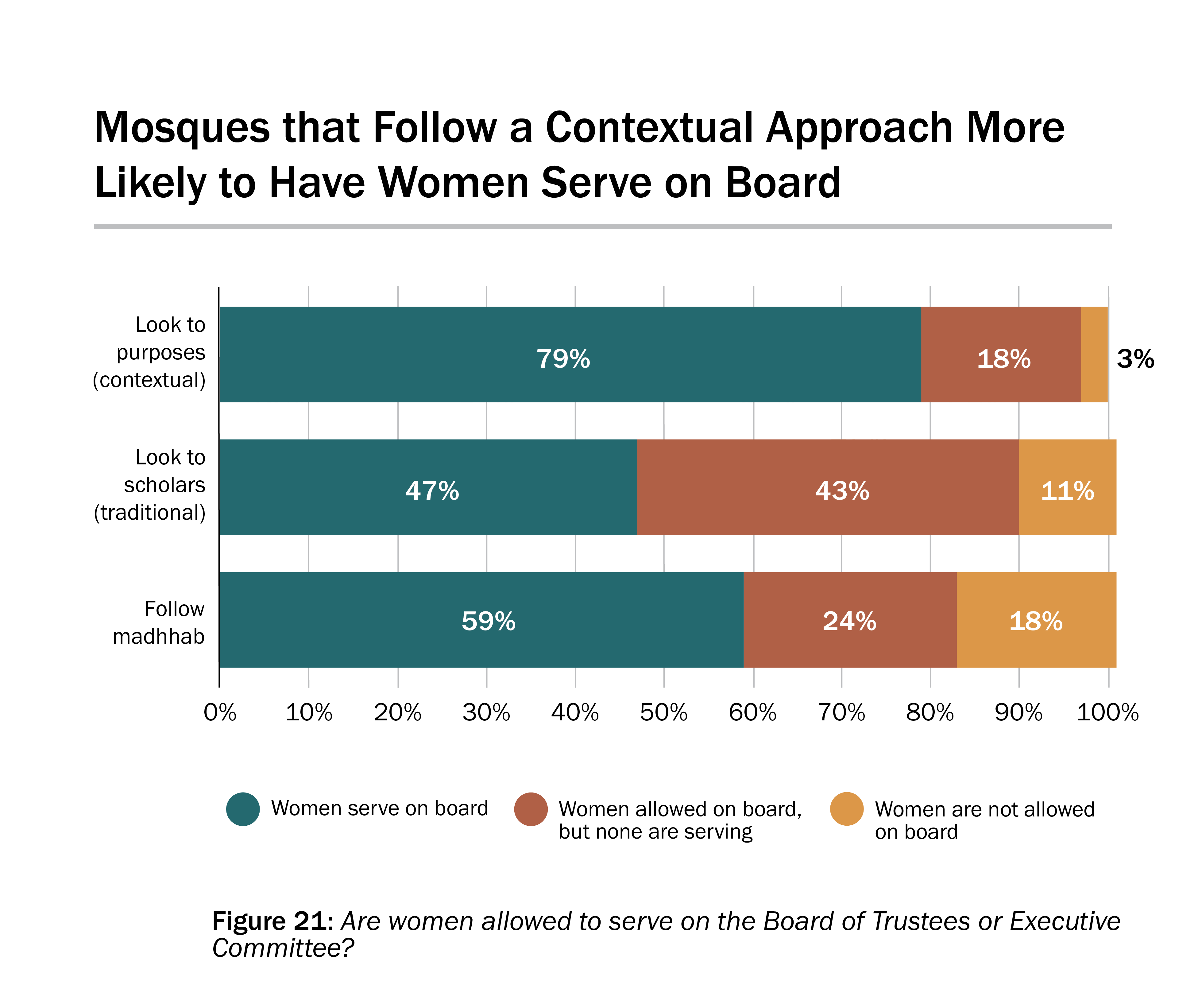

Those mosques that look to the purposes have a much higher percentage of women on their boards: 79% of these mosques have women serving on their boards.

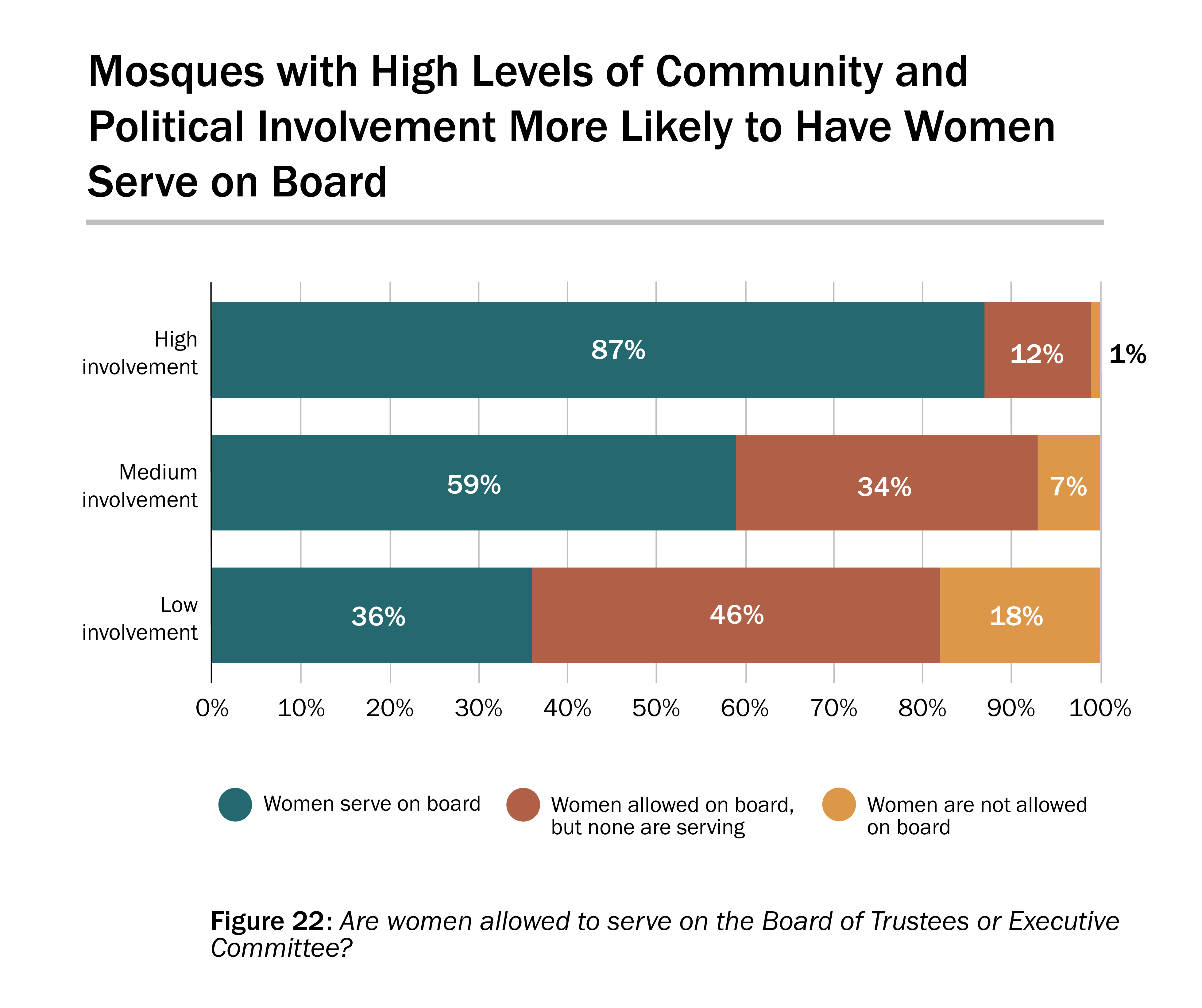

High levels of community and political involvement are also associated with women serving on mosque boards.

Women’s Attendance at Jum’ah Prayer

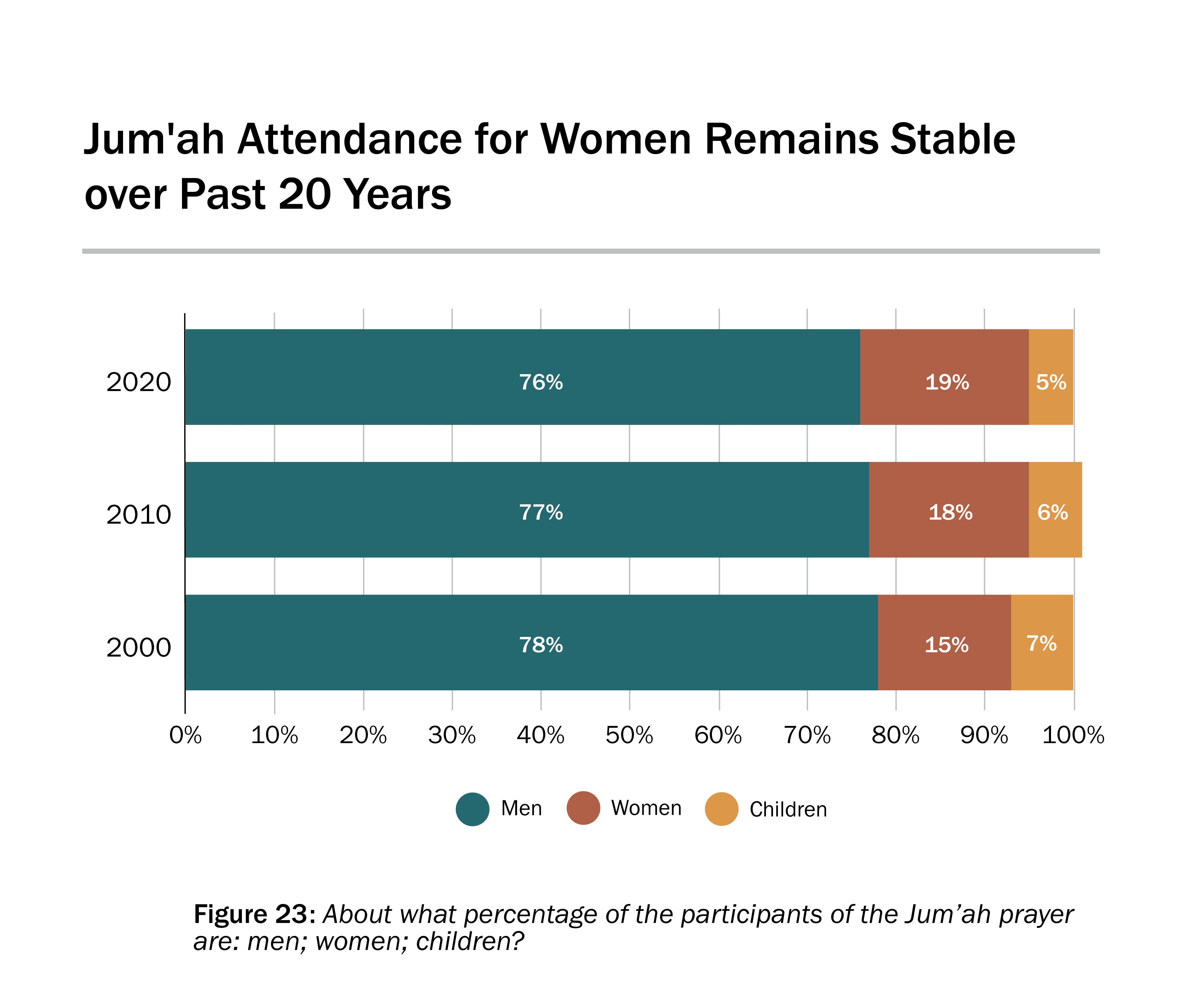

The percentage of women attending the Jum’ah prayer has not changed significantly over the past two decades. In 2020, the percentage of women attending Jum’ah prayer was 19%, in 2010 it was 18%, and in 2000 it was 15%. The low percentage of women attending Jum’ah prayer might simply be an indication that mosques have not changed sufficiently to make Jum’ah attendance more attractive to women. Another factor is that the majority of Muslim women are still first-generation immigrants who carry the understanding based on the traditional culture and religious prescriptions from their home countries that women do not need to attend Jum’ah prayer.

African American mosques have a higher percentage of women attendees at Jum’ah prayer: 23% of their Jum’ah attendance comprises women as compared to 18% for immigrant mosques.

The mosque’s Islamic approach is also a factor for women attending Jum’ah prayer. Mosques that follow the more flexible approach of looking to the purposes of the law have a higher percentage of women attendees than mosques that follow either the great scholars of the past or a madhhab. For mosques who follow the purposes of the law, 21% of their Jum’ah attendees are women as compared to 16% for mosques that follow the great scholars of the past and 15% for mosques that follow a madhhab.

Higher female attendance is also associated with those mosques that score high in community and political involvement. In mosques with high community involvement, women make up 21% of their Jum’ah attendance; for those mosques that score medium in community involvement, 19% are women; and for those that score low, 14% of their Jum’ah attendance are women.

The size of an immigrant mosque also seems to affect women’s attendance. Small immigrant mosques, whose overall attendance is 100 and below, have a smaller percentage of women attendees: For these small mosques, about 14% of their Jum’ah attendees are women. In larger mosques with Jum’ah attendance over 100 people, the average percentage of women attendees is 20%. The reason behind these figures is most probably that larger mosques better accommodate women by giving them more space. (African American mosques tend to be small, so they were separated to better determine the connection to size.)

As with dividers in the mosque, a mosque that has a full-time paid, American-born imam is more likely to have a higher attendance rate for women. For the mosque led by a full-time paid, American-born imam, the Jum’ah attendance for women averages 24% as opposed to a full-time paid, foreign-born imam whose mosque has an attendance rate for women at 18%.

Finally, mosques that have women on their boards have a higher percentage of women attendees than other mosques. Mosques with women on their boards have 21% of Jum’ah attendees comprising women as compared to 13% for mosques who do not allow women on their boards and 15% for mosques that allow women but do not have a woman on their board.

Women’s Programs in the Mosque

As reported in the section on mosque activities, 77% of mosques have women’s activities and 55% have a women’s group.

The size of the mosque as measured by Jum’ah attendance is a major factor in whether a mosque has women’s activities and a women’s group. The larger the mosque, the greater the likelihood of a mosque having women’s activities and a group.

As with the analysis of mosque activities, Islamic approach does not affect whether a mosque has women’s activities or a women’s group. No Islamic approach is against women getting together to have their own activities or to organize their own groups.

Immigrant mosques do a better job of having women’s activities and a women’s group than African American mosques. The likely reason is that African American mosques tend to be small (63% of African American mosques have 100 or less in Jum’ah attendance), and women in general are better integrated in all activities of the African American mosque.

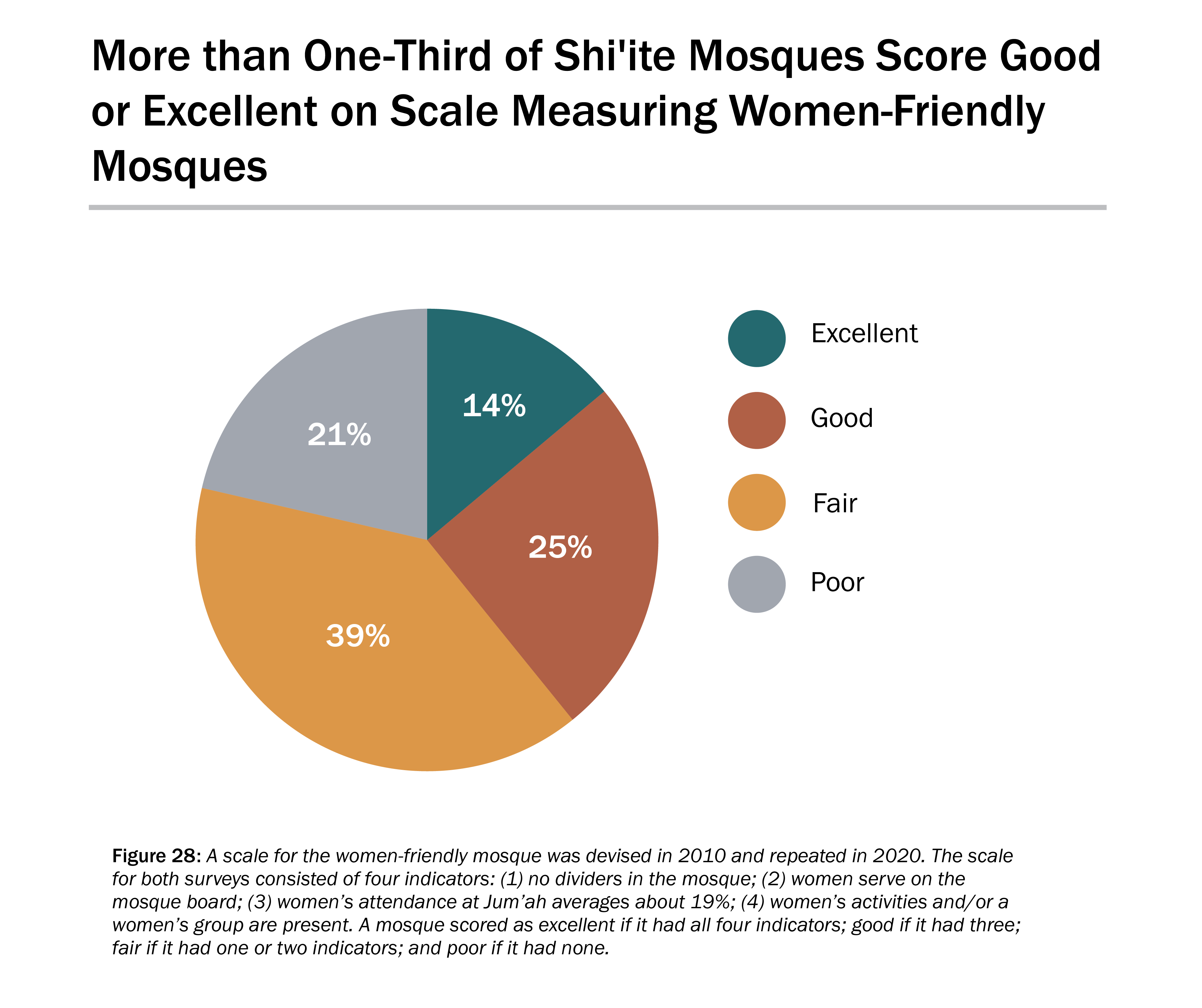

The Women-Friendly Mosque

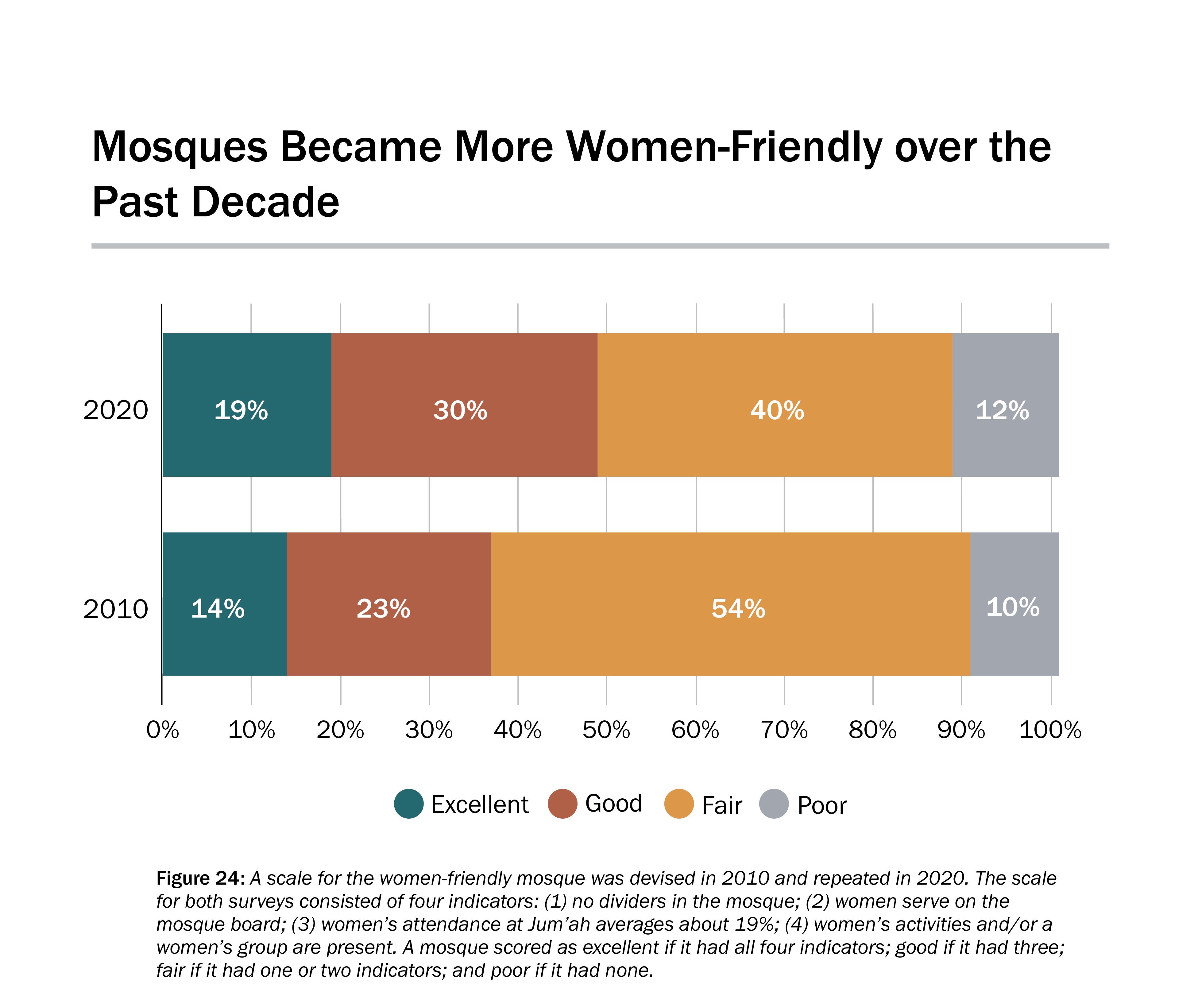

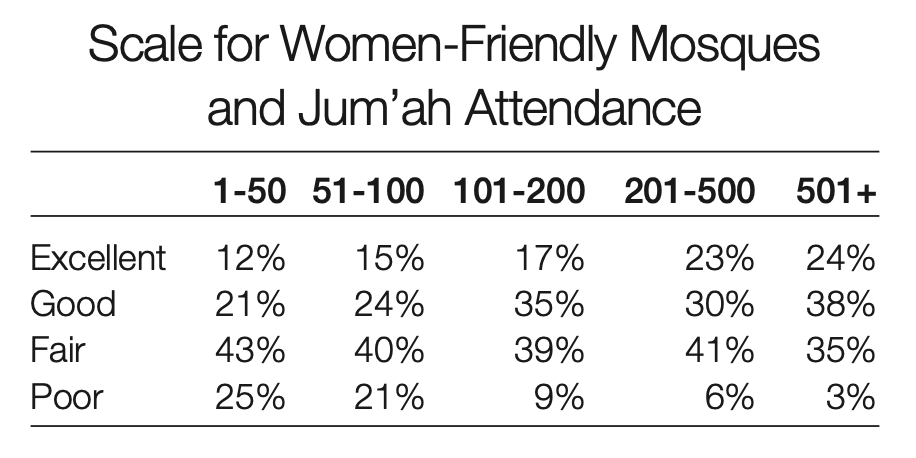

A scale for the women-friendly mosque was devised in 2010 and repeated in 2020. The scale for both surveys consisted of four indicators: (1) no dividers in the mosque; (2) women serve on the mosque board; (3) women’s attendance at Jum’ah averages about 19%; (4) women’s activities and/or a women’s group are present. A mosque scored as excellent if it had all four indicators; good if it had three; fair if it had one or two indicators; and poor if it had none.

The good news is that scores for women-friendly mosques improved from 2010 to 2020. In 2020, 19% of mosques scored excellent while in 2010 only 14% scored excellent; in 2020, 30% of mosques scored well in comparison to 23% in 2010.

The bad news is that the needle has not moved significantly as the majority of mosques (52%) score fair or poor. Also, only 19% of mosques can be truly designated as women-friendly mosques. This is not a high percentage.

High scores for being women-friendly is associated with five factors: high Jum’ah attendance, being an African American mosque, high scores for community and political involvement, preferring the more flexible Islamic approach of looking to the purposes, and having a full-time paid, American-born imam.

Jum’ah attendance is a factor in affecting the women-friendly score but not as much a factor as in other aspects.

Almost one-third (34%) of African American mosques score excellent as compared to 16% of immigrant mosques.

High scores for community and political involvement are also associated with women-friendly mosques. For example, 39% of mosques that score high for community involvement score excellent in being women-friendly mosques.

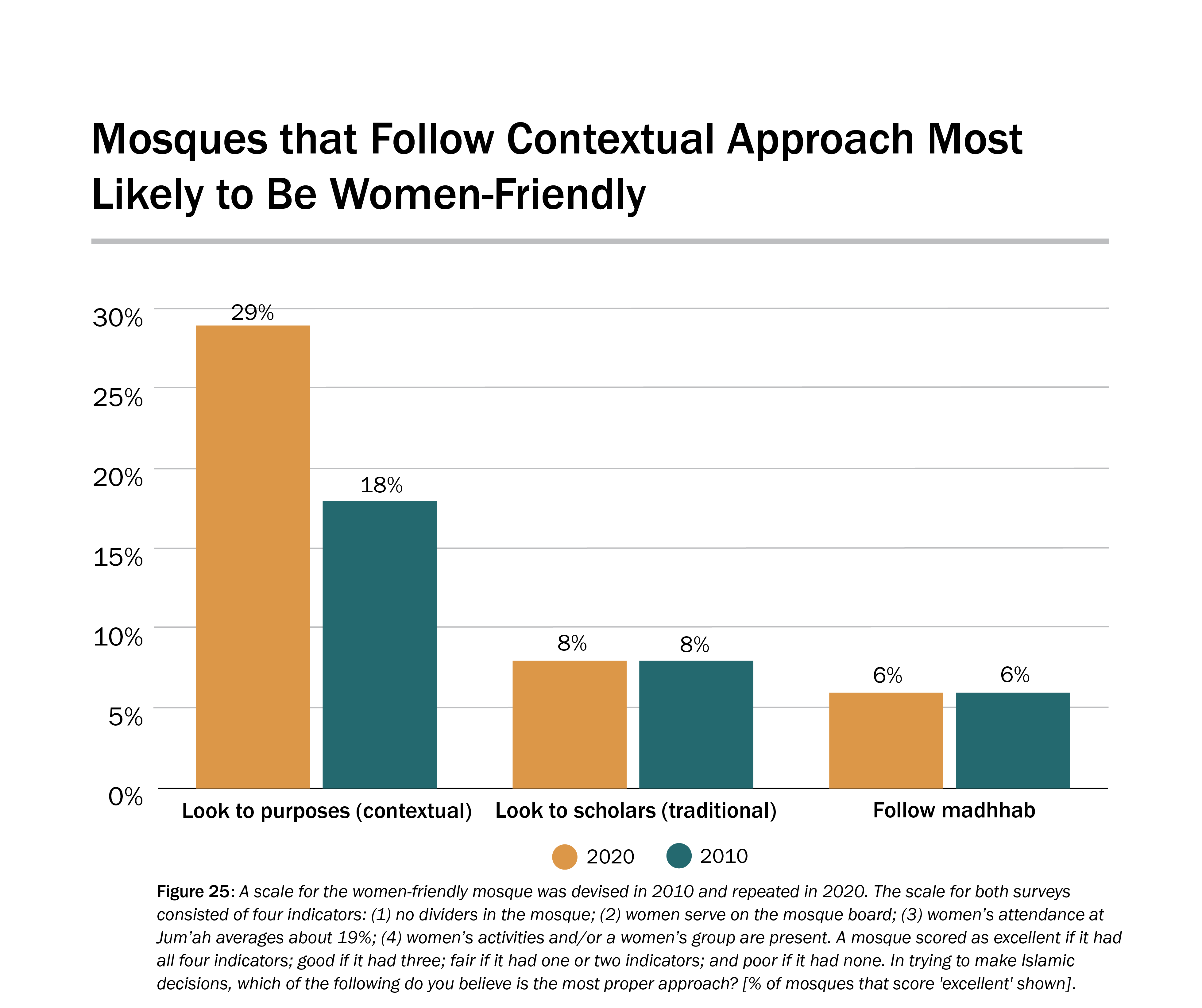

Mosques that follow the flexible Islamic approach of looking to the purposes of the texts are much more likely to be women-friendly: 29% of mosques that follow the flexible approach score excellent as compared to 8% of mosques that follow the great scholars of the past and 6% of mosques that follow a madhhab.

Mosques that look to the purposes of the Qur’an and Sunnah experienced a significant increase from 2010 to 2020 in the number of mosques that scored excellent as women-friendly mosques: 18% scored excellent in 2010 and 29% scored excellent in 2020. Mosques that follow the other approaches showed no change.

Almost one-third of mosques (32%) that have a full-time, American-born imam score excellent as opposed to 18% of mosques with a foreign-born imam.

.

Shi’ite Mosques: Perspectives and Activities

The results of the US Mosque Survey as detailed in Reports 1 and 2 include both Shi’ite and Sunni mosques. However, it was thought appropriate to have a separate section for Shi’ite mosques to reveal similarities and differences with Sunni mosques.

Islamic Approach

One of the main differences between Shi’ites and Sunnis is the methodology of arriving at an Islamic decision. Therefore, the US Mosque Survey had two questions about Islamic approach—one for Sunnis and one for Shi’ites.

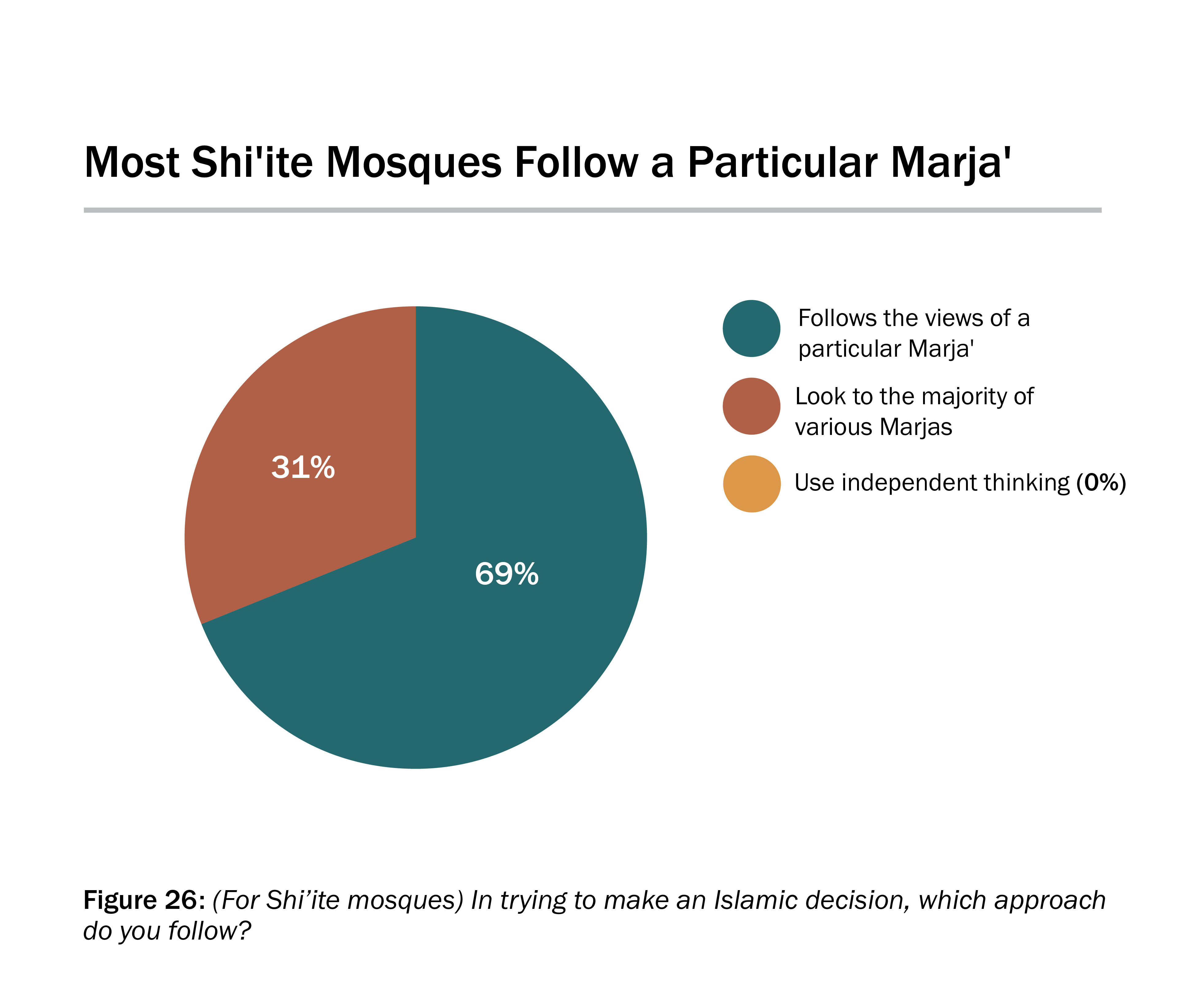

The three possible approaches in the questionnaire for Shi’ite leaders are:

-

- Follow the views of a particular Marja’ (religious authority)

- Look to the majority of various Marjas

- Use independent thinking

A Marja’ is an authoritative religious figure who provides rulings on various questions. In mainstream Shi’ite theology, Shi’ite followers should have a living Marja’ that they follow. It is safe to say that the main Marja’ in the Shi’ite world today is Grand Ayatollah Al-Sayyid Al-Sistani in Iraq (he is of Iranian origin). A Marja’ is bound to look to the Islamic texts and the opinions of imams of the past, but they are given leeway to use their own independent reasoning.

Only 13 Shi’ite leaders answered this question, so the results should be viewed with caution because of the small sample.

A follow-up question for those who answered that they followed a particular Marja’ was which Marja’ they follow. In response, nine of the 13 (69%) stated that they follow al-Sistani; one stated that they follow Grand Ayatollah Mohammad Fadlallah (the mosque leader commented that they should not be following Fadlallah because he died in 2010, but the mosque’s Lebanese attendees were attached to him); and one stated that they follow Imam Abdul Latif Berry, the only Marja’ in America.

Perspectives on American Society

No differences exist between Shi’ite and Sunni mosque leaders in terms of their view of involvement in America and their views on American hostility to Islam and American immorality.

As for the two questions regarding whether Muslims should participate in American civic society or the American political process, Shi’ite leaders like their Sunni counterparts are virtually unanimous in that Muslims should be involved in American society: 96% of Shi’ite mosque leaders agreed to both questions about involvement.

Mosque leaders were asked whether they think that American society is hostile to Islam. Again, the responses of Shi’ite and Sunni leaders were virtually the same. Few agreed that America is hostile to Islam, and the rest were evenly divided between disagreeing or being neutral. Among Shi’ite leaders 11% agreed that America is hostile while 44% disagreed and 44% were neutral.

Another question asked whether respondents viewed America as an immoral society. Again, Shi’ite and Sunni leaders responded similarly: Few agreed with the statement; most disagreed. Among Shi’ite leaders only 15% agreed with the statement; 59% disagreed that America is immoral.

Basic Mosque Activities: Worship, Educational, and Group Activities

Worship

The main differences between the Shi’ite and Sunni mosques relate to worship activities. Only 14% of Shi’ite mosques hold all daily prayers as compared to 77% of Sunni mosques. (Shi’ites combine the noon and mid-afternoon prayers and the sunset and evening prayers, and if the Shi’ite mosque does this, they were coded to have held all five prayers.) Almost two-thirds of Shi’ite mosques (64%) do not hold any daily prayers as compared to 8% of Sunni mosques. Performing the daily prayers in the mosques is not emphasized in Shi’ite thought.

One regular worship activity that is found in Shi’ite mosques but not Sunni mosques is the Thursday evening gathering where special prayers are recited. The special prayer is called Du’a Kumail. Almost all Shi’ite mosques (93%) hold the Thursday evening service.

Much of the religious calendar of Shi’ite mosques revolves around the celebration of various events in the lives of the imams and their families. Unfortunately, the Mosque Survey did not capture this aspect of the religious life of Shi’ite mosques.

Educational Activities

Shi’ite mosques, like Sunni mosques, emphasize weekend schools for children and Islamic study classes: 81% of Shi’ite mosques have a weekend school and 71% have some form of Islamic study classes. A growing phenomenon in Sunni mosques is the Qur’an memorization school which meets throughout the week. A parallel activity is not found in Shi’ite mosques. Only 7% of Shi’ite mosques organize such a school as compared to 28% of Sunni mosques.

Group Activities

There is virtually no difference between Shi’ite and Sunni mosques in terms of group activities. The most common type of activities in both mosques are community gatherings, youth activities, and women’s activities. Less common are youth groups and women’s groups while young adult and senior activities are rare.

Social Service Activities

No distinction exists between Shi’ite and Sunni mosques in terms of social service activities. The vast majority of both Shi’ite and Sunni mosques distribute zakah and provide marital and family counseling; almost half of both mosques engage in food distribution, health education programs and social justice efforts. Few are involved in tutoring programs, mental health counseling, and refugee programs.

Interfaith Activities

Again, no significant differences exist between Shi’ite and Sunni mosques in interfaith activities. Over two-thirds of both Shi’ite and Sunni mosques engage in interfaith educational programs; a little over half are involved in interfaith community service programs; and a little less than half participate in interfaith worship services.

Scale for Community Involvement

A scale was created to measure involvement of mosques in their local communities. (See the discussion of this scale on page 13 of the report PDF.) As might be expected, there is no significant difference between Shi’ite and Sunni mosques in community involvement. Over one-fourth score high, and those mosques who score medium and low are somewhat evenly divided. A factor strongly associated with the community involvement score for both mosques is the size of the mosque: Mosques with more attendees score higher in community involvement.

Although the sample size is too small to make any firm conclusions, there nevertheless seems to be a difference between Shi’ite mosques that follow one Marja’ (in almost all cases al-Sistani) and Shi’ite mosques that follow the consensus of Marjas. Two-thirds (67%) of mosques that follow one Marja’ score high or medium in community involvement as compared to 25% of mosques that follow the consensus of Marjas who score high or medium.

Political Activities and Scale for Political Involvement

The one area of activities where Shi’ite and Sunni mosques differ is in political involvement. Shi’ite mosques are significantly less involved than Sunni mosques. As an example, approximately 54% of Sunni mosques are involved in voter registration and inviting politicians to their mosques; in comparison, 29% of Shi’ite mosques are involved in these two activities.

The scale to measure political involvement (see page 15 of the report PDF for a full discussion of the scale) reflects the same distinction between Shi’ite and Sunni mosques. Only 7% of Shi’ite mosques score high on political involvement, whereas 26% of Sunni mosques score high.

It is not clear whether Shi’ite mosques are simply more reluctant to be involved in politics or the smaller size of Shi’ite mosques is an overwhelming obstacle to political involvement.

As in the case of community involvement, Shi’ite mosques that follow one Marja’ score much higher in political involvement than mosques that follow a consensus of Marjas.

Women and the Mosque

Shi’ite and Sunni mosques are virtually identical when it comes to issues concerning women. For both Shi’ite and Sunni mosques, a little over one-third do not have a divider in the main prayer area and over two-thirds have women serving on the mosque board. Women’s attendance at Jum’ah prayer averages 19%. Over three-fourths of both mosques have women’s activities and over half have a women’s group.

Scale for the Women-Friendly Mosque. As might be expected, there is no significant difference between Shi’ite and Sunni mosques regarding the scale for the women-friendly mosque: both score low.

Only 14% of Shi’ite mosques score excellent; 60% score fair or poor.