.

.

Covering American Muslims Objectively + Creatively

A Guide for Media Professionals

Quick Links

Introduction

Why ISPU?

Successful Media Approaches

Media Checklist

Busting Common Myths about American Muslims

American Muslims: An Overview

A Primer on Sunni + Shia Muslims

Accurate Language

Key Terms + Definitions

Covering Muslims: Beyond the Security Lens

Tips for Improving Depth of Coverage

Media + Ideologically Motivated Violence

Avoiding Double Standards

Understanding Shariah

Women + Gender Roles

Additional Resources

Research Team + Advisors

Sources

.

.

Covering American Muslims Objectively + Creatively

A Guide for Media Professionals

Quick Links

Introduction

Why ISPU?

Successful Media Approaches

Media Checklist

Busting Common Myths about American Muslims

American Muslims: An Overview

A Primer on Sunni + Shia Muslims

Accurate Language

Key Terms + Definitions

Covering Muslims: Beyond the Security Lens

Tips for Improving Depth of Coverage

Media + Ideologically Motivated Violence

Avoiding Double Standards

Understanding Shariah

Women + Gender Roles

Additional Resources

Research Team + Advisors

Sources

Introduction

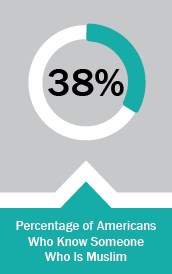

The majority of Americans say they do not know a Muslim. For many of these Americans, what they know about Muslims comes from media representations.

However, according to media content analysis, more than 80 percent of television media coverage of Islam and Muslims in the United States is negative.

Such narrow media representations open the door to distorted public perceptions of American Muslims, especially in the absence of any first-hand knowledge of this diverse community.

The role of the media in informing the public has never been more important, especially when it comes to marginalized communities. At the same time, journalists are constantly asked to cover more and more, with less resources.

We created this guide to help.

Note: ISPU intends this page to be a living document regularly updated with new research, graphs, guides, and additional resources.

.

Why ISPU?

The Problem: A lack of data on American Muslims and dearth of Muslim voices in media and policy circles

The Solution: A research organization focused on the trends, opportunities, and challenges of American Muslims

ISPU PROVIDES…

SOURCES

Direct access to over 40 experts on issues related to Muslims in the United States

NUMBERS

The latest survey data on demographics, religiosity, civic engagement, and attitudes towards political and social issues

NEW IDEAS

Background on issues seldom discussed helps bring new perspectives to breaking news and current events

Why should journalists turn to ISPU? This short video will explain.

Since 2002, ISPU has provided data-driven education to:

- Media organizations

- The Department of Justice

- The White House

- Schools and universities

- Community leaders and groups

- Interfaith leaders

- General public

- And many more…

.

Successful Media Approaches

1.

Expand the voices that inform your reporting.

Muslims come from all walks of life, as well as diverse ethnic and racial backgrounds. They play a variety of roles in their communities. Include Muslim voices in stories about what concerns all Americans. This includes the voices of:

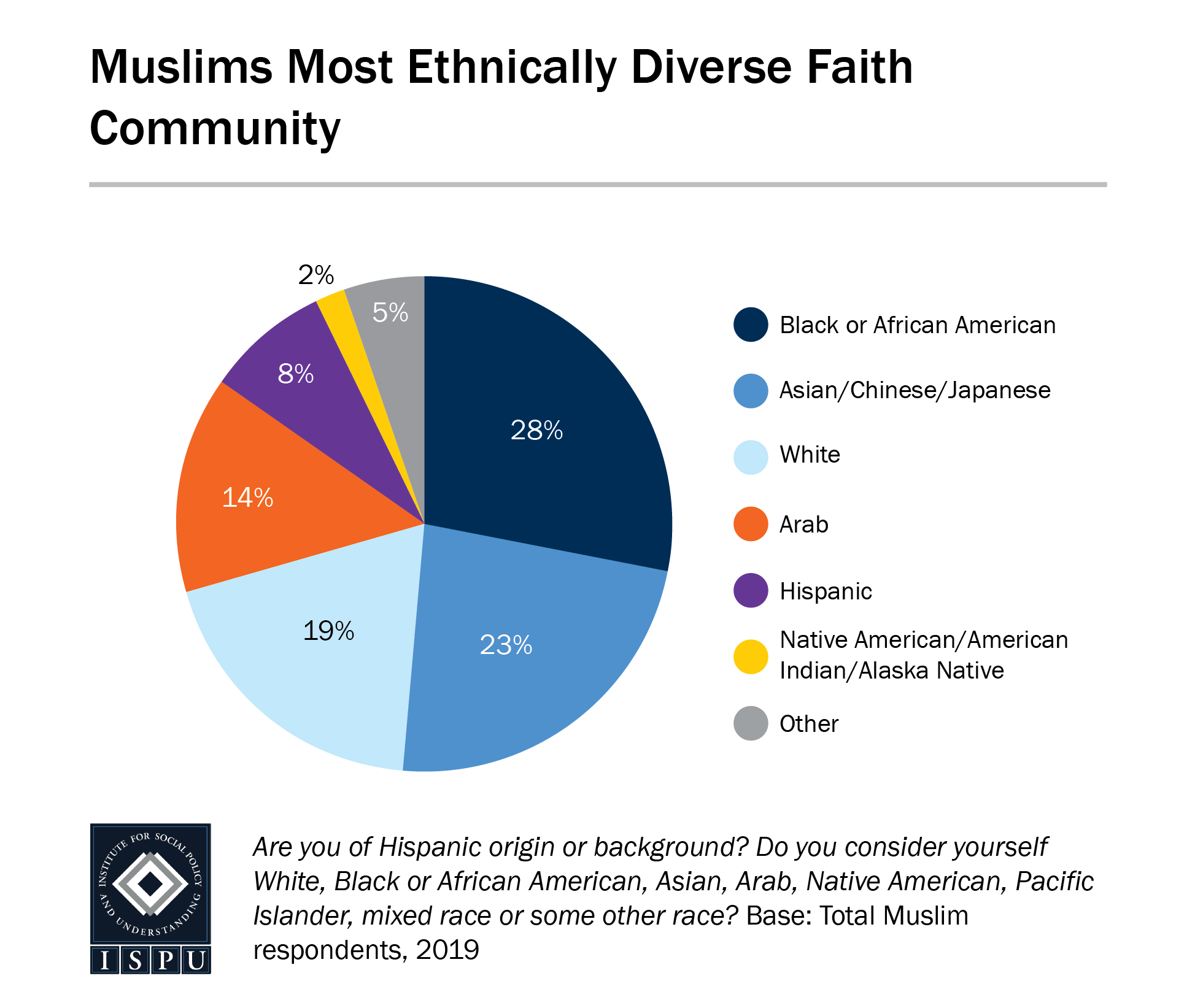

- Black or African American Muslims, who make up 25–33% of all American Muslims (Learn more about Black Muslim experiences→)

- Women

- Both native-born and immigrant American Muslims

2.

Move beyond the security lens.

Cover stories about American Muslims not framed around national security or criminal violence. Shed light on the diverse roles American Muslims play in their communities, and provide a more accurate, nuanced portrait of who American Muslims really are.

3.

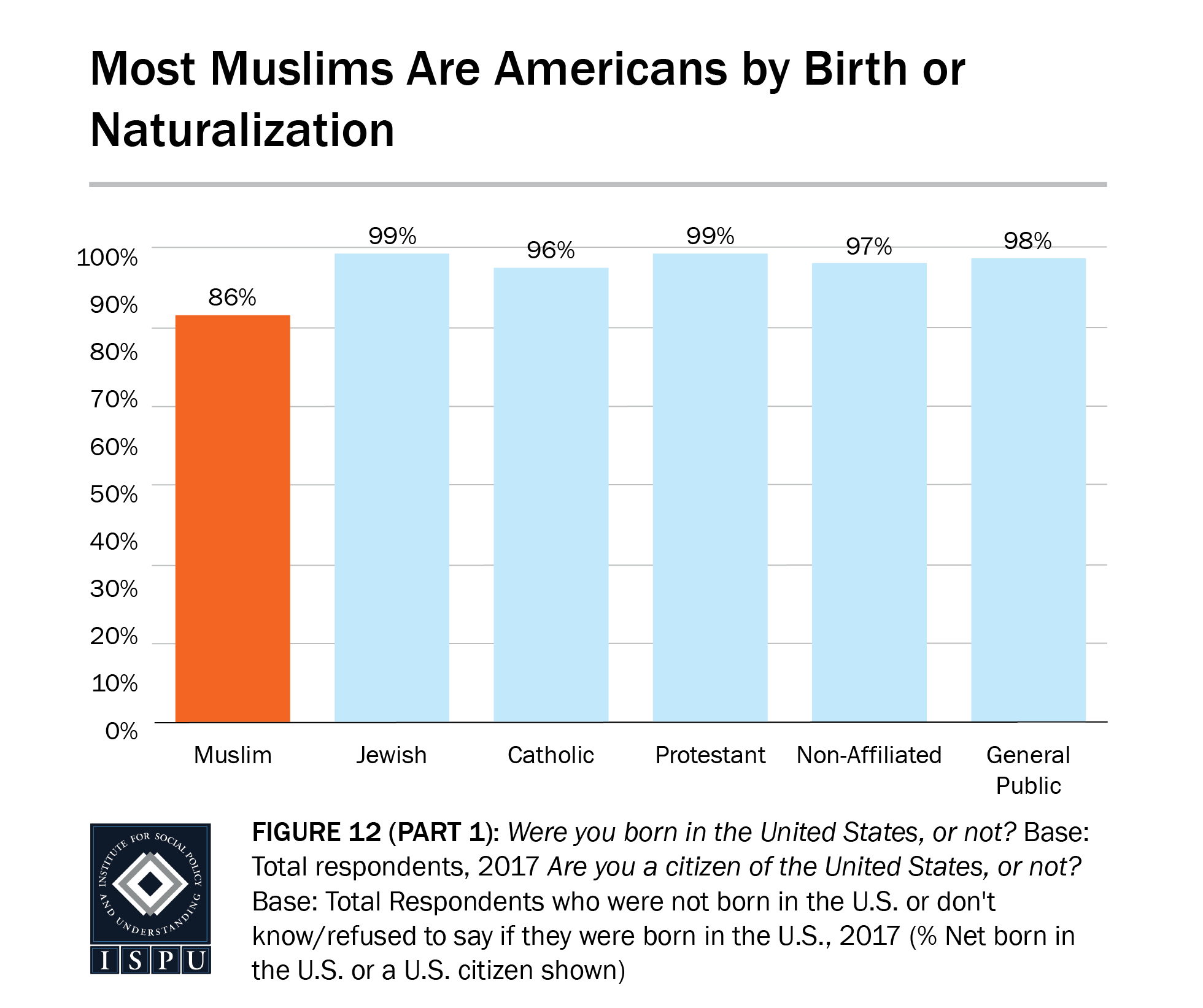

Treat Americans that are Muslims as just that—American.

There has never been an America without Islam and Muslims; they were early explorers, enslaved Africans, and immigrants from around the world. Casting Islam and Muslims as foreign, non-American, and “other” is inaccurate. Rather, rightly cast Muslims as a part of the diverse fabric of American society.

4.

Avoid implicating religion as the sole explanation for negative behavior.

Americans that are Muslim are complex human beings, and their motivation is complex. Don’t assume religion is the driver of their behavior.

5.

Be factual and avoid loaded or Orientalist language.

The use of culturally specific language to describe human behaviors that are not unique to Muslims makes such behaviors seem pathological to these communities. For example, domestic violence affects Muslim communities no more than other faith (and non-faith) communities. Reference to such incidents should be to domestic violence, not “honor crimes.”

Precious Rasheeda Muhammad speaks about Black Muslims and their centuries-long ties to the making of America, reminding journalists of the plurality of Muslim communities. Learn more about Black Muslim experiences→

SCHOLAR SPOTLIGHT:

Precious Muhammad

Author, award-winning speaker, historian, poet, publisher, Harvard-trained researcher

Areas of Expertise: History of Islam in America, American Muslim diversity

.

Media Checklist

✅ Does my media outlet feature the voices of Americans that are Muslim in contexts outside of violence and public safety?

✅ Is my media outlet including Muslim voices in stories about subjects that concern all Americans?

✅ Does my coverage of American Muslims feature reliable mainstream Muslim experts and sources?

✅ Am I being representative and including Black Muslim voices in my reporting on “Muslim stories”?

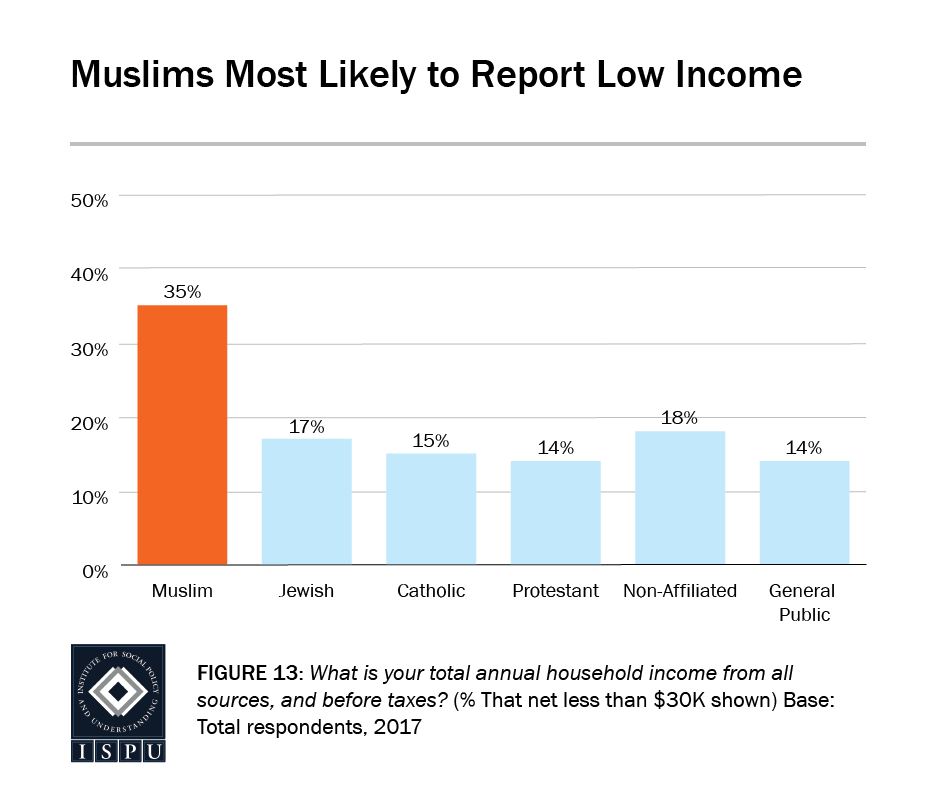

✅ Am I considering what factors other than religion and ethnicity might explain the behavior in question? Could trauma or economic factors be a more powerful variable than ethnicity or religion?

✅ Have I included the voices of American women who are Muslim in my reporting that represent the vast majority of women’s experiences (Islam-positive, educated, and more challenged by racism and Islamophobia than Muslim misogyny, according to ISPU’s American Muslim Poll 2018)?

✅ Am I using culturally neutral language? Arabic words or culturally specific language is often used to describe behaviors that are not unique to Muslims or Arabs, making the behavior seem pathological to these communities. Before using such language, it is helpful to ask yourself: Am I assigning foreign (“Muslim-sounding”) words to a universal human behavior? What would I call this type of behavior if it didn’t involve a Muslim person?

✅ Is my story driven by the priorities and points of view of the majority? If not, am I qualifying it as a minority point of view?

.

Busting Common Myths about American Muslims

Despite empirical evidence to the contrary, many misconceptions and damaging stereotypes about American Muslims often are repeated in mainstream media and go unchallenged. The following are data-driven responses to common misconceptions.

1.

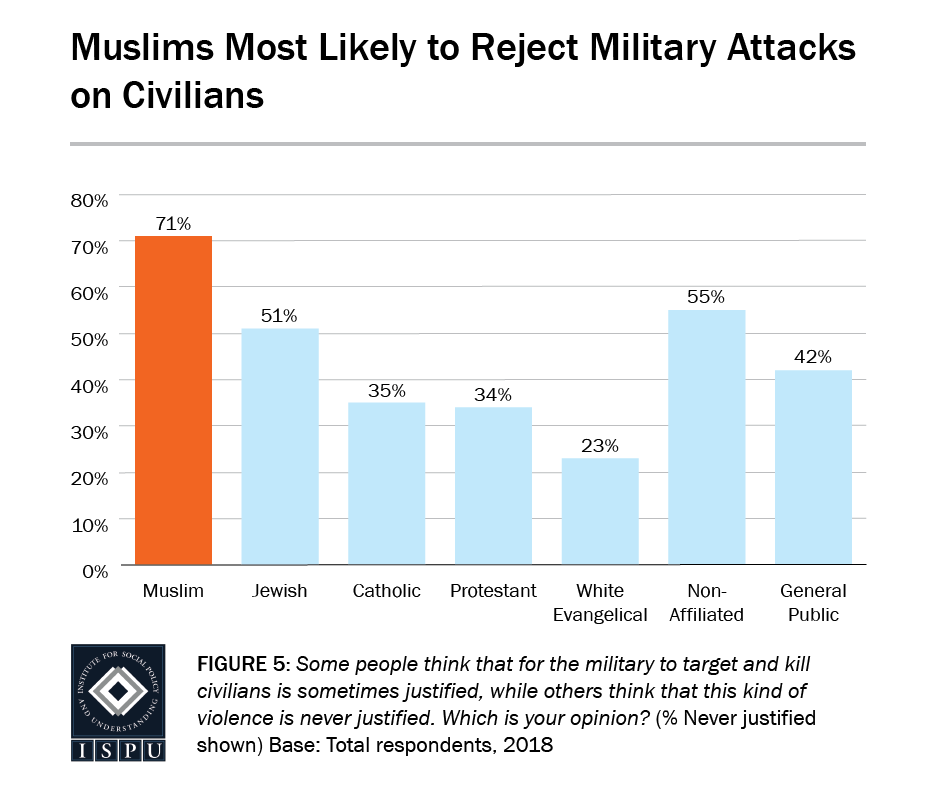

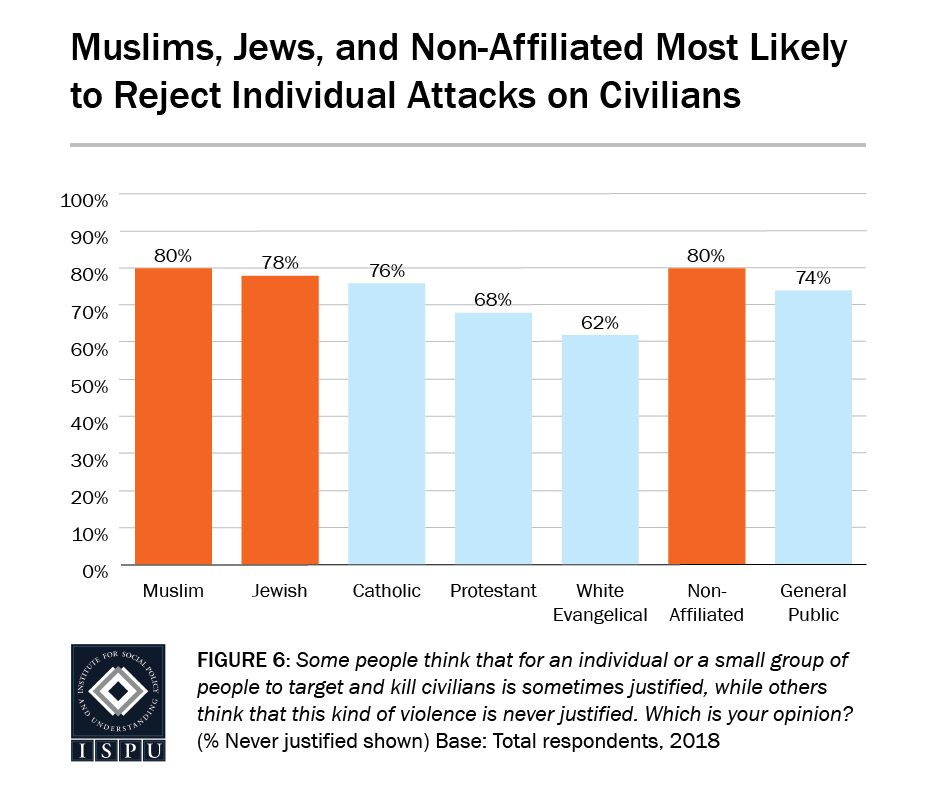

FACT: Muslims are one of the most likely groups in the United States to reject violence.

ISPU’s American Muslim Poll 2018 found that Muslims were the least likely to accept both military and individual violence against civilians.

2.

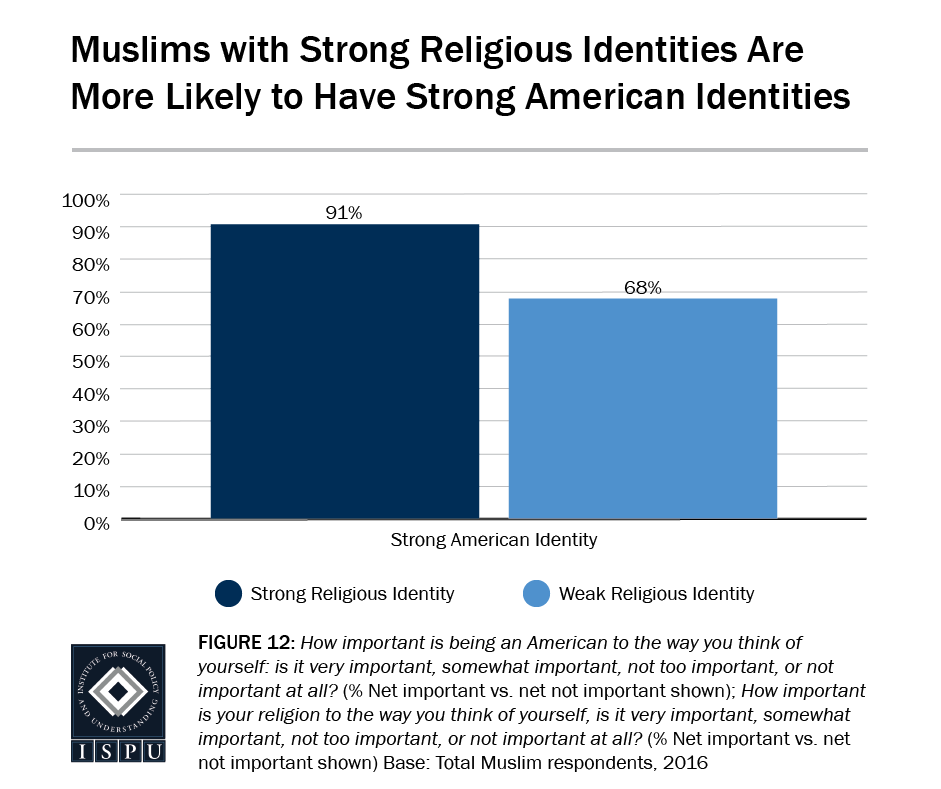

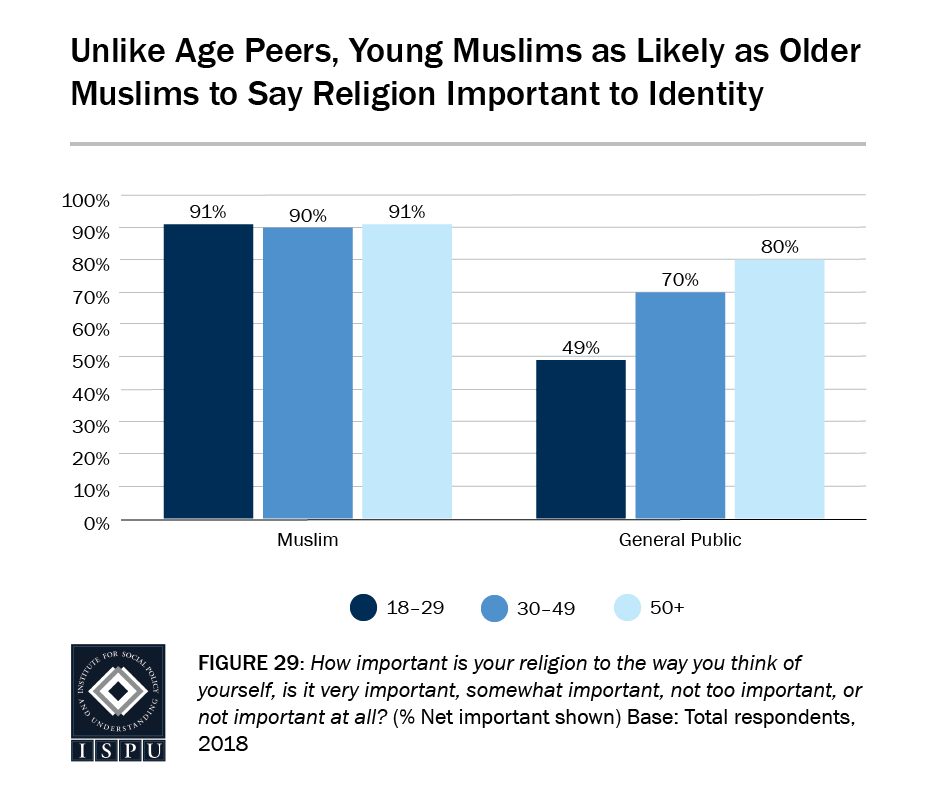

FACT: A strong Muslim identity is directly correlated with a strong American identity.

Such data challenges the myth that Americanness and Muslimness are mutually exclusive.

3.

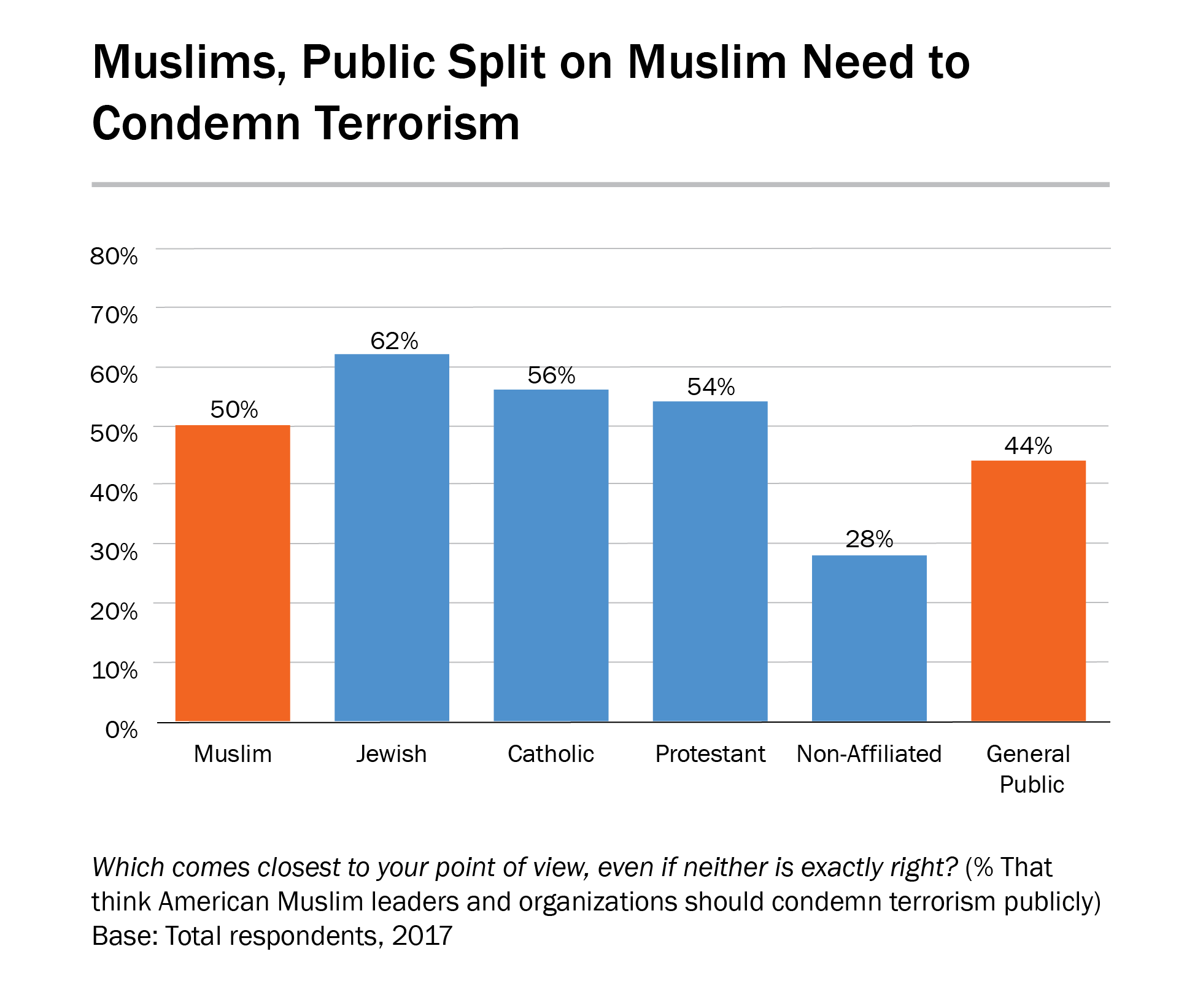

FACT: American Muslim leaders and organizations have consistently and repeatedly condemned violence and denounced violent ideologies.

But should they be expected to? Or are such expectations based in bigotry and Islamophobia? ISPU recently examined attitudes surrounding this debate. In ISPU’s 2017 American Muslim Poll, 50% of American Muslims and 44% of the general public responded that American Muslim leaders should condemn ideologically motivated violence publicly.

One point of of view: ISPU Director of Research Dalia Mogahed says, “When [acts of ideologically motivated violence perpetrated by non-Muslims] occur, we don’t suspect other people who share their faith and ethnicity of condoning them. We assume that these things outrage them just as much as they do anyone else. And we have to afford this same assumption of innocence to Muslims.”

4.

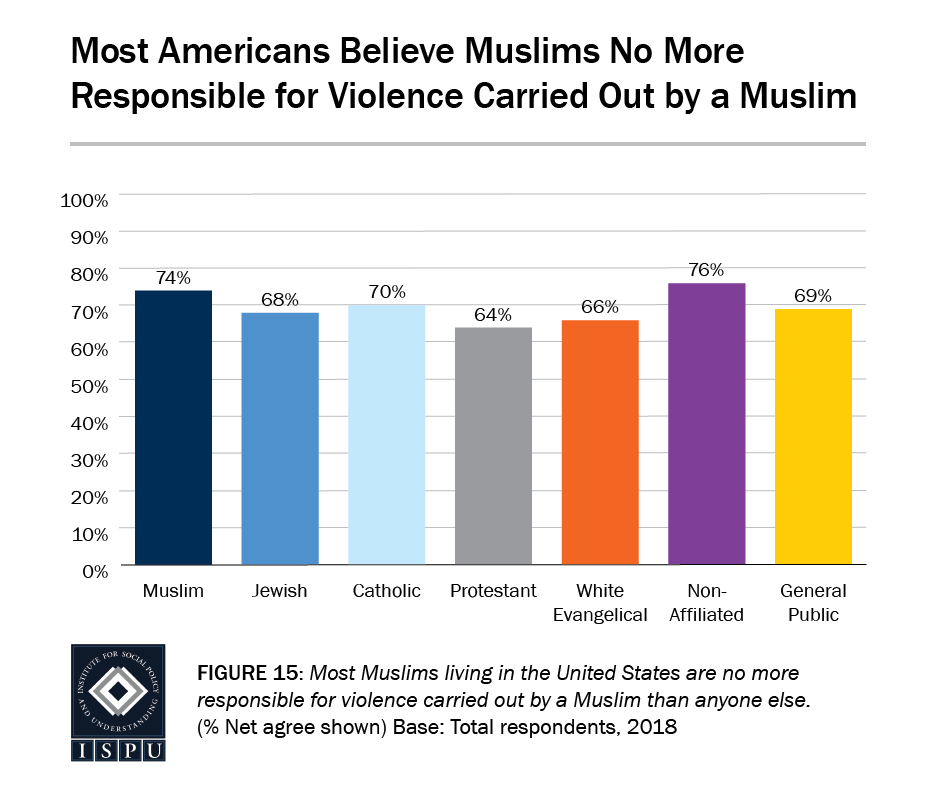

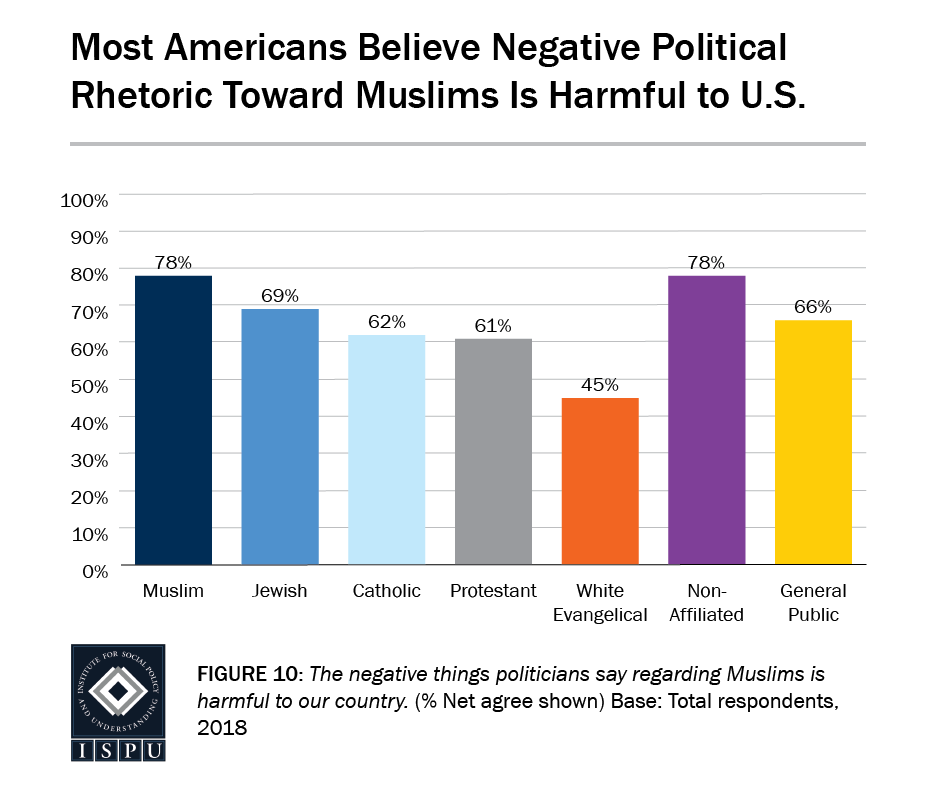

FACT: Most Americans agree that Muslims are no more responsible for violence carried out by a Muslim than anyone else.

Most Americans also agree that negative political rhetoric toward Muslims is harmful to the United States.

5.

FACT: Violence by perpetrators perceived to be Muslim receives far more media attention than other types of ideologically motivated violence.

A recent study by ISPU found that perceived Muslims accused of a violent plot received more than seven times the media attention as their non-Muslim counterparts, despite similarities in their alleged crimes. Similarly, Muslim-perceived perpetrators accused of violent acts were referenced in the media more than four times the rate of their non-Muslim counterparts.

6.

FACT: Muslims who bring up religious-based claims in court are not attempting to change the laws of the United States.

Individual Muslims determine the role of religious rules in their lives depending on their personal beliefs. If a legal dispute arises involving one of those rules, individuals will likely find themselves in litigation, raising claims before an American judge. Anti-shariah legislation restricts the rights of American Muslims to apply religious rules to their lives. This type of legislation is also strongly linked to other forms of bigotry and a legislative agenda aimed at excluding various minority communities from the political landscape.

7.

FACT: The concept of taqiyyah refers to a religious permission to conceal one’s faith if revealing it endangers one’s life, not an open license to lie.

As explained by American Muslim scholars, nothing in Islam gives Muslims general permission to lie. The origin of the notion of taqiyyah refers to the permissibility for Muslims to conceal their faith if identifying as Muslims puts their lives in danger.

8.

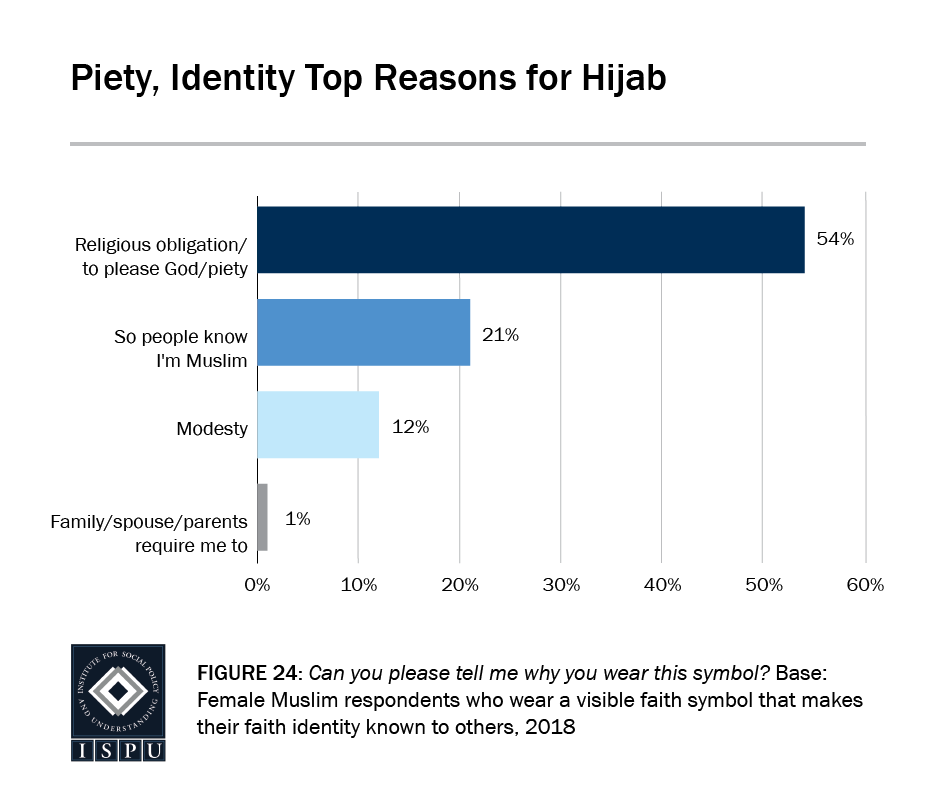

FACT: By an overwhelming margin, Muslim women choose how they dress.

ISPU recently asked American Muslim women why they wear an identifying religious symbol like hijab. 99 percent of respondents indicated personal reasons for wearing hijab, such as piety or the desire to be identified as a Muslim.

9.

FACT: The overwhelming majority of American women who are Muslim say Islam is a source of pride and happiness in their lives.

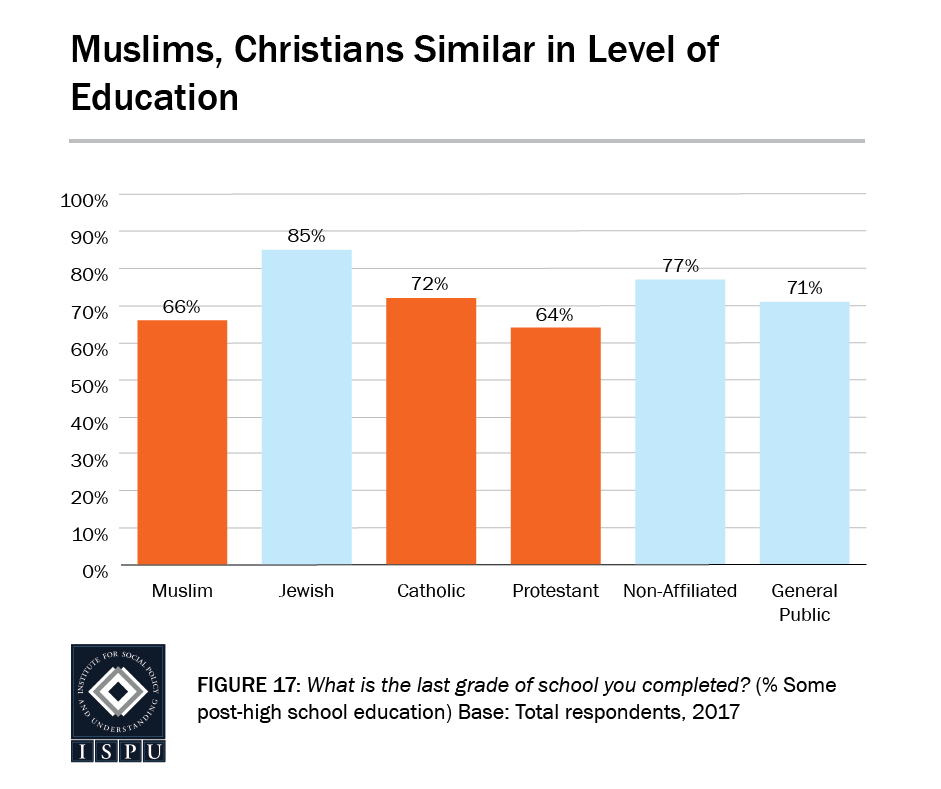

American women who are Muslim are one of the most educated female religious groups in the United States. They also overwhelmingly view their faith as a source of happiness and a part of their identity for which they feel a great deal of pride. As described in a recent ISPU policy brief, the rights afforded to women by Islam in the seventh century include the right to a consensual marriage, to remain their own legal entities after marriage, to initiate a divorce, to child support, to own property, to pursue education, and to be involved in social and political affairs. Many Muslim women rise to the tops of their professions as doctors, lawyers, and scholars. A recent study suggests U.S. news media’s disproportionate focus on gender discrimination in Muslim societies contributes to stereotypes that Muslims are distinctly sexist and misogynistic.

.

American Muslims: An Overview

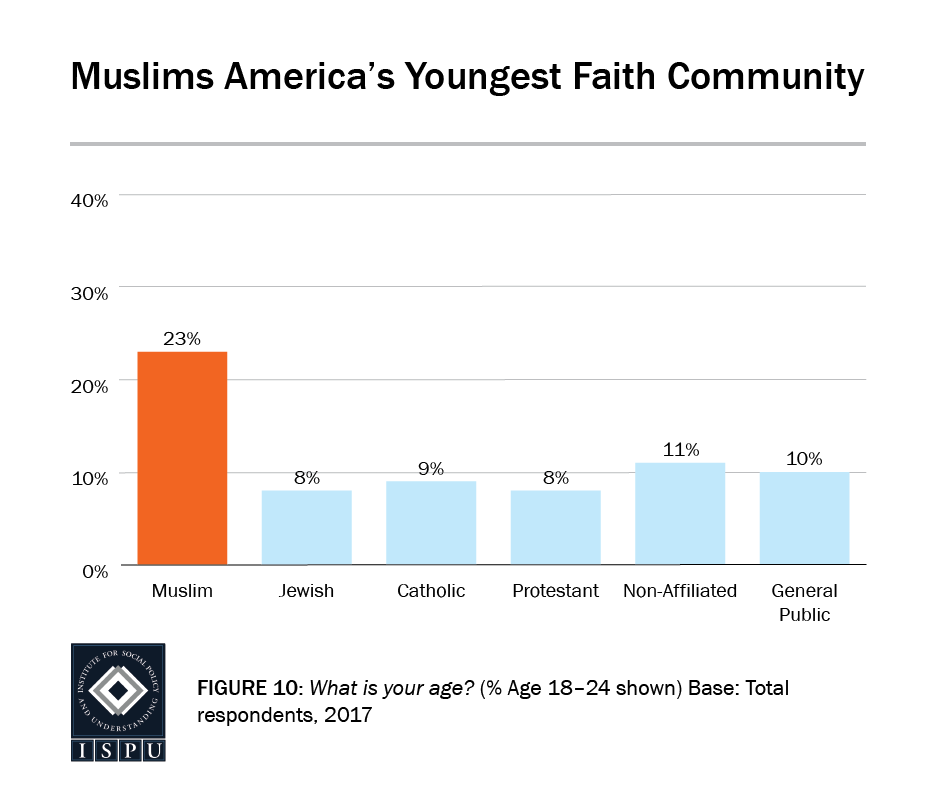

Muslims make up about one percent of the population in the United States and are the fastest growing and most diverse religious community in the nation.

Dalia Mogahed conducts a brief overview of American Muslims. Who are they? Why does the media matter? And how can journalists replace fear with facts? Learn even more from Dalia by watching her free Poynter webinar for journalists.

SCHOLAR SPOTLIGHT:

Dalia Mogahed

ISPU Director of Research

Areas of Expertise: Public opinion, Islamophobia, Muslim women, American Muslim demographics

Facts at a Glance

DEMOGRAPHICS

ATTITUDES + CHALLENGES

CONTRIBUTIONS

ISPU’s Muslims for American Progress study quantifies the impact of Muslims on U.S. communities.

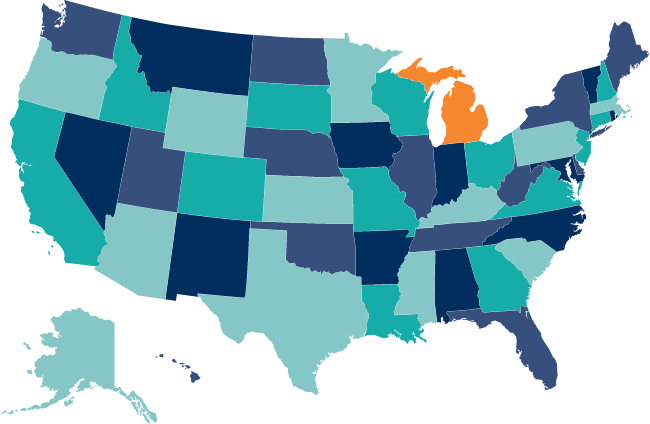

In just the state of Michigan, for example, where Muslims make up only 2.75 percent of the population, Muslims contribute to every sector of society. A Michigan without Muslims would lose:

- More than 1600 new inventions

- Medical care for 1.6 million patients

- Social services for 24,000 families

- The education of 30,000 K-12 students

- The creation of 100,000 jobs

- $5.5 billion from its economy

- The representation of 2.3 million constituents

- $117 million in charitable giving

Why It Matters

ISPU data on the diversity and demographics of the Muslim community has implications for journalists seeking to accurately represent American Muslims. Journalists might ask themselves:

- Who is speaking for the community?

- Are sources representative of the community’s diversity?

.

A Primer on Sunni + Shia Muslims

As explained by the Islamic Networks Group:

- The majority of both Sunnis and Shias share the core beliefs of Islam and adhere to the Five Pillars.

- The main differences between them today are their sources of knowledge and religious leadership.

- In addition to the Quran and hadiths, the Shias and the many sects that comprise them rely on the rulings of their Imams and resulting variations in beliefs and practices.

- Historically, the difference originated from the question of succession after the death of the Prophet Muhammad and is related to differing views about appropriate leadership for the Muslim community.

The largest division of Islam

Close to 90 percent of the world’s Muslim population

Understood as an umbrella identity with no centralized clerical institution

Include adherents to the four extant schools of fiqh (religious law or understanding) including the Hanafi, Maliki, Shafii, and Hanbali

Believe in the legitimacy of the order of succession of the first four Muslim caliphs

The second largest division of Islam

Believe Ali (cousin and son-in-law of the Prophet Muhammad) was the rightful leader of the early caliphate

.

Accurate Language

PROBLEMATIC

These words have been politicized and misrepresented, and are often are used as slurs.

Terror(ist/ism)

According to a recent study, the word “terrorist” was used in media headlines far more often in reference to perpetrators perceived as Muslim than those who are not for similar ideologically motivated crimes.

PREFERRED

These are neutral, clear, informative alternatives to commonly misused words.

When reporting on ideologically motivated violence, use fact-based language to describe groups, persons, and events at hand. For example, describe perpetrators as “militia,” “gunmen/women,” “bombers,” etc.

PROBLEMATIC

Islamist (ism)

According to the Merriam-Webster dictionary, this term refers specifically to “a popular reform movement advocating the reordering of government and society in accordance with laws prescribed by Islam.” The majority of these movements are nonviolent and shouldn’t be lumped together with those claiming Islam sanctions their violence.

PREFERRED

There is no causal relationship between religious adherence and violence. We’ve never lumped the Lord’s Resistance Army and the Ku Klux Klan together as “Christianist terrorists,” even though both claim to act in the name of Biblical teachings. Instead, we simply use the group name. Do the same for all groups.

PROBLEMATIC

Jihad

Literally, the word “jihad” means “struggle” and most often refers to the inner struggle against one’s own evil impulses, such as greed, anger, and malice. According to Muslim theologians, armed jihad is a heavily regulated military engagement where non-combatants, livestock, and even trees cannot be harmed.

PREFERRED

Individuals who commit ideologically motivated violence and claim their actions are sanctioned by Islam should not be referred to as engaging in “jihad,” nor should they be called “jihadis” or “jihadists.” Use fact-based language to describe groups and events. Use the same standards in all coverage of ideologically motivated violence in your newsroom.

PROBLEMATIC

Islamic State

The group that refers to itself as “The Islamic State,” known also as ISIS/ISIL, has been denounced by nearly every major cleric of Islam as un-Islamic.

PREFERRED

We recommend Daesh, which is the acronym of ISIL in Arabic, just as we say Hamas, which is the acronym for a longer Arabic name for the group. Current AP style guidance doesn’t use “The Base” for Al-Qaeda. Similarly, we shouldn’t translate other words. In all instances possible, use accurate, unloaded terms. The alternatives are ISIS/ISIL.

.

Key Terms + Definitions

The diversity of Muslim communities results in a diverse array of terminology. Here are some commonly used terms:

Alhamdulillah

Thank God

Aqeedah

Religious creed

Eid

A Muslim holiday

Eid Al-Fitr

Holiday that marks the end of Ramadan, the Islamic holy month of fasting

Fard

An Islamic term that denotes a religious duty commanded by God

Fiqh

Islamic jurisprudence

Hajj

Pilgrimage to Mecca

Hadith

Traditions containing sayings of the Prophet Muhammad that constitute the major source of guidance for Muslims apart from the Quran

Iftar

A meal eaten by Muslims breaking their fast after sunset during the month of Ramadan

Imam

A Muslim prayer leader; can also mean congregation leaders that fulfill organizational and pastoral needs of a mosque

Inshallah

God willing

Juma’ah

Friday noon prayer

Khutbah

Sermon given during the Friday noon prayer

Masjid

A Muslim place of worship

Mosque

A Muslim place of worship

PBUH

Peace Be Upon Him; a prayer said by Muslims after the Prophet’s name out of reverence

Quran

Central religious text of Islam, which Muslims believe to be a revelation from God

Ramadan

Month of fasting, when the Quran was first revealed

Salaam

Greeting of peace

Salah

A prayer; usually referring to the five daily prayers required of all Muslims as one of the pillars of Islam

Shahadah

The testimony of faith (There is no deity but God. Muhammad is the messenger of God)

Sheikh

A religious leader

Sunnah

The “path” or “example” of the Prophet Muhammad

Tafseer

The Arabic word for Quranic exegesis or interpretation

.

Covering Muslims: Beyond the Security Lens

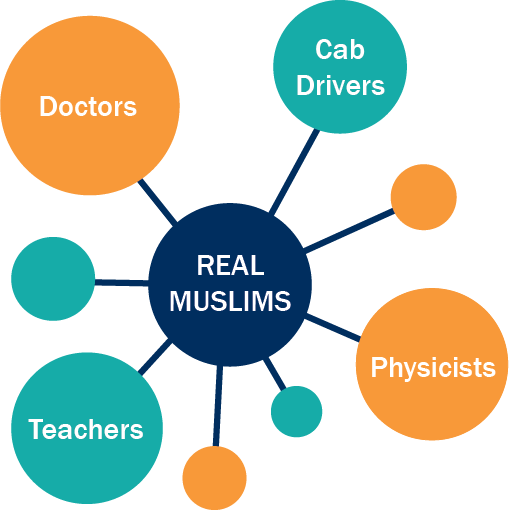

American Muslims are often viewed through a security lens, cast as either good or bad from a purely security-oriented perspective.

- Stories about “bad Muslims,” who are violent or likely to act violently, and the rare “good Muslim” who is “rooting out extremism in his own community” dominate the American imagination about American Muslims.

- Americans of the Islamic faith are much more than this binary. They are doctors, cab drivers, school teachers, engineers, and physicists.

- Moving beyond the security lens to include such voices provides a more accurate portrayal of American Muslims.

.

Tips for Improving Depth of Coverage

Relationships of trust between media professionals and individuals in the American Muslim communities produce better, richer reporting. The following tips, adapted from the Religion Communicators Council, help improve depth of coverage.

DOs

✅ Do work actively to form connections with local, national, and international Muslims to establish a relationship.

✅ Do attend a local, national, or community event.

✅ Do focus on interesting stories done by Americans who just happen to be Muslims.

✅ Do write on American Muslim stories that are not framed around ideologically motivated violence.

✅ Do find value in American Muslim experiences and contributions other than helping national security or countering violent crime.

✅ Do write more stories about the lives of American Muslim women not involving the hijab, burqa, domestic violence, or FGM.

DON’Ts

❌ Don’t assume all hijab-wearing women (or bearded men) are religious Muslims.

❌ Don’t assume all uncovered women (or clean-shaven men) are not religious Muslims.

❌ Don’t wait for an event dealing with Muslims to develop sources. Develop a source list and make it available to colleagues.

❌ Don’t use the word “unveil” in your title.

❌ Don’t assume any person claiming to represent Muslim communities really does.

❌ Don’t use fringe Muslims as representatives for diverse Muslim communities.

❌ Don’t say the “Muslim world.” There is no “Muslim world.”

❌ Don’t assume all Muslims can speak accurately about Islam.

.

Media + Ideologically Motivated Violence

Kumar Rao and Carey Shenkman explain how the media covers ideologically motivated violence differently when the perpetrator is perceived to be Muslim versus not perceived to be Muslim.

SCHOLAR SPOTLIGHT:

Kumar Rao

ISPU Scholar, Senior Staff Attorney at the Center for Popular Democracy

Areas of Expertise: Law and public policy, criminal justice, racial justice, media and communications

SCHOLAR SPOTLIGHT:

Carey Shenkman

ISPU Scholar, attorney, litigator, author

Areas of Expertise: Human rights, Constitutional Law

ISPU recently examined the factors that shape media coverage of individuals who plan or carry out crimes in the name of violent ideologies. Our 2018 report found that:

- Media coverage of perpetrators of ideologically motivated violence perceived to be Muslim differed from those not perceived to be Muslim in striking ways. Those perceived to be Muslim received:

- Twice the absolute quantity of print media coverage for violent crimes carried out

- Seven and a half times the coverage for “foiled” plots

- Greater references to their religion

- Greater mention of specific phrases such as “terrorist” or “terrorism”

- Increased coverage of the ultimate prison sentences

- In the legal system, perpetrators of ideologically motivated violence perceived to be Muslim differed from those not perceived to be Muslim:

- Perceived Muslims receive four times the average prison sentence.

- Undercover law enforcement provided the means of the crime (such as a firearm or inert bomb) in a majority (two-thirds) of convictions involving a perceived Muslim perpetrator, but in a small fraction (2 out of 12) of those involving a non-Muslim.

Equal treatment? Not quite… Watch this short video for a quick summary of some of the key findings of our Equal Treatment? report.

.

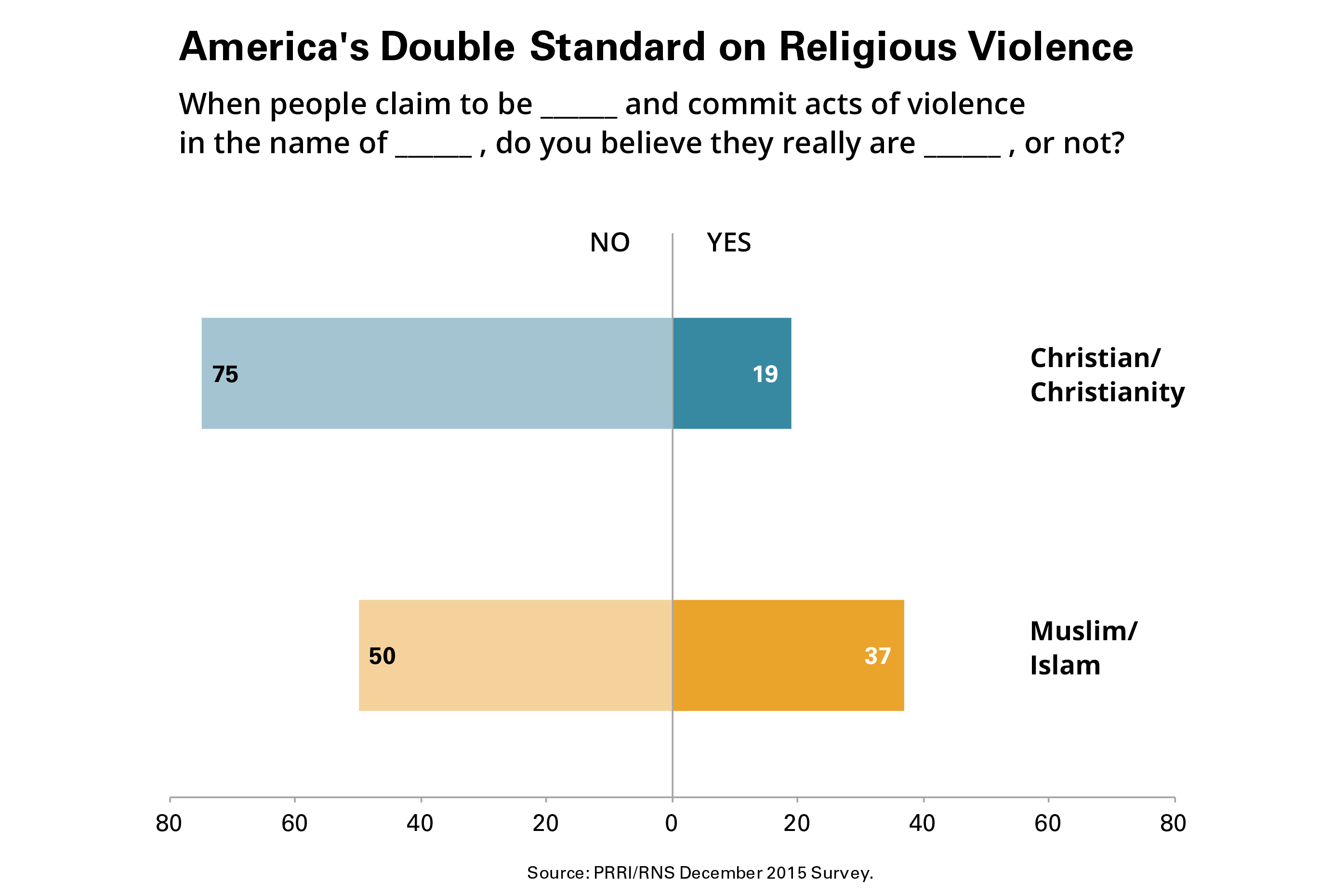

Avoiding Double Standards

Covering crime and violence in all its forms is a challenge many journalists face. The following recommendations, based on the Asian American Journalists Association reading of ISPU’s Equal Treatment? report, help inform journalists’ reporting on ideologically motivated violence.

1.

Context Is Important

Many experts agree that white supremacists and right-wing extremists pose a more serious threat to Americans than individuals who falsely claim Islam sanctions their crimes. Rather than paint them as “lone wolves,” coverage of these extremists should include the context of this growing national threat. Discuss the wider social norms that have normalized Islamophobia and other forms of bigotry rather than casting the horrors of an attack as coming out of nowhere.

According to ISPU and Georgetown’s Bridge Initiative’s Islamophobia Index, endorsing a set of five anti-Muslim tropes is directly linked to support for violence targeting civilians. Bigotry is not only immoral—it can also be lethal.

2.

Details Matter

Law enforcement rarely discuss the documented role of informants and agent provocateurs in motivating and operationalizing terror plots that would have never manifested without the law enforcement asset. Journalists need to ask law enforcement about their active involvement in these plots, or lack of, and mention it in all coverage.

3.

Define Ideologically Motivated Violence Consistently in All Stories

Every newsroom needs to have a discussion on whether and when to use the terms “terror/terrorism/terrorist.” The word “terrorism” is highly politicized and many governmental agencies have their own various definitions. We recommend moving away from the word “terrorism” and using instead “ideologically motivated violence,” which is a neutral term. The standards should be the same regardless of the suspect’s background or views. Use actual, concrete terms to describe what has happened, not buzzwords that will inflame.

4.

Don’t Assume Race, Religion, or Ethnicity Are Relevant

Newsrooms should discuss when a suspect/offender’s race, ethnicity, religion, or national origin are relevant. Using descriptors of race, ethnicity, religion, or national origin when they’re not relevant or without explaining their relevance can perpetuate harmful stereotypes. Such stereotypes prevent discussions on how mental illness and other systemic problems can lead to violent attacks or plots.

5.

Question Authority

Journalists covering ideologically motivated violence must question prosecutors and investigators over why they are or are not calling something terrorism, why they’ve chosen to charge a suspect with particular crimes, and what evidence they have for their charges.

6.

A Press Release Is a Press Release

ISPU’s report found the Justice Department sent out six times more press releases for offenders perceived as Muslim than offenders who were not, and ideology was highlighted more often in the former than in the latter. Journalists need to read between the lines, ask questions about language used and facts omitted, and verify details.

7.

Examine Why You’re Covering or Not Covering a Particular Story

Journalists should examine what they’re covering, what they’re not covering, and ask newsroom decision-makers why. Some basic rules should apply: Does the reporting give background and context? Does it offer diverse voices? Does it follow up on events or situations to gain greater insights as well as measures of change or impact?

8.

Avoid Using Mental Illness As Speculative Motivation for Violence

Be cautious not to diminish acts of violence by casually and without evidence using the language of mental illness. This is unfair to people who are mentally ill, who are more likely to be the victim of violent crime than perpetrators of one. Blaming acts of violence on mental illness before facts are known is a way to deflect accountability and dismiss the violence as an aberration rather than the product of systemic societal problems.

9.

Center the Impacted Communities

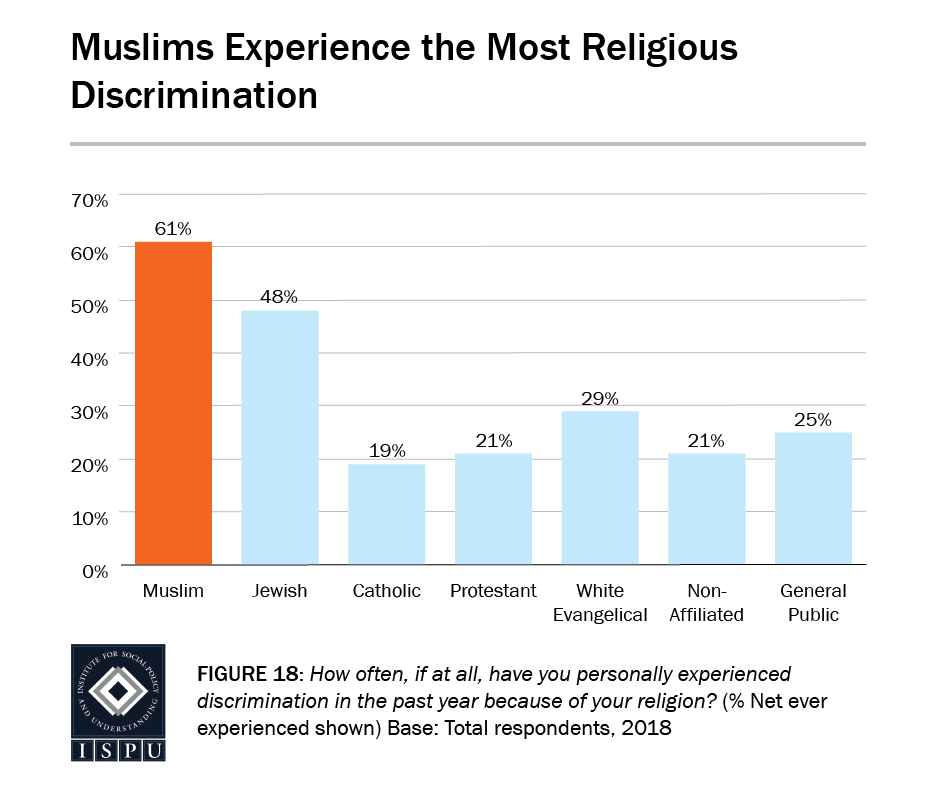

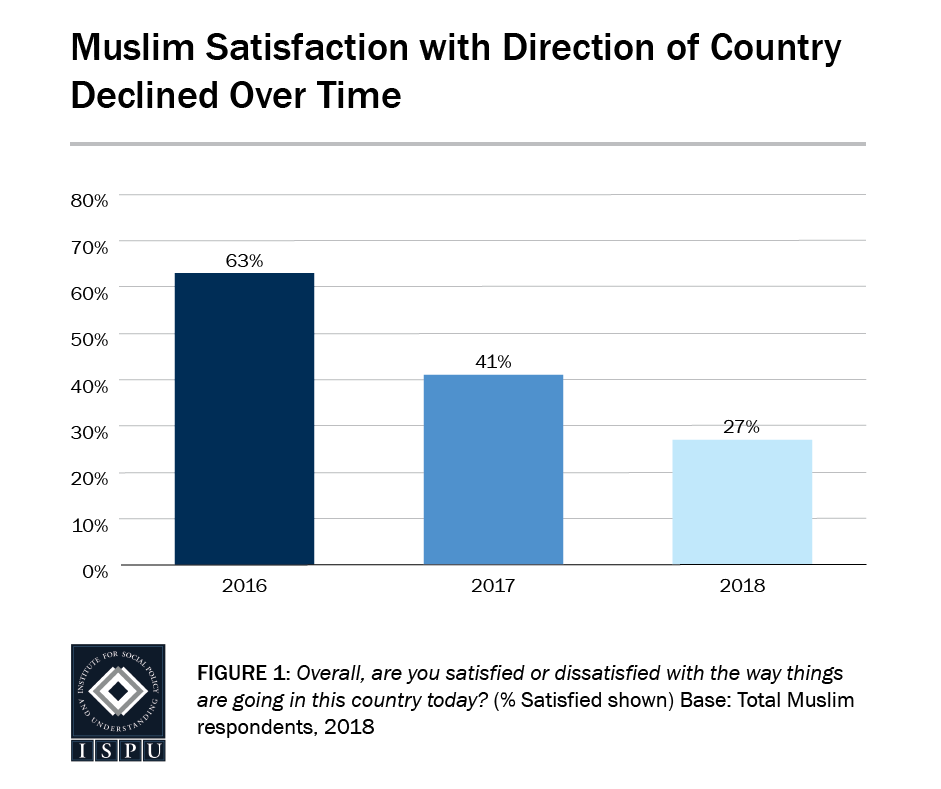

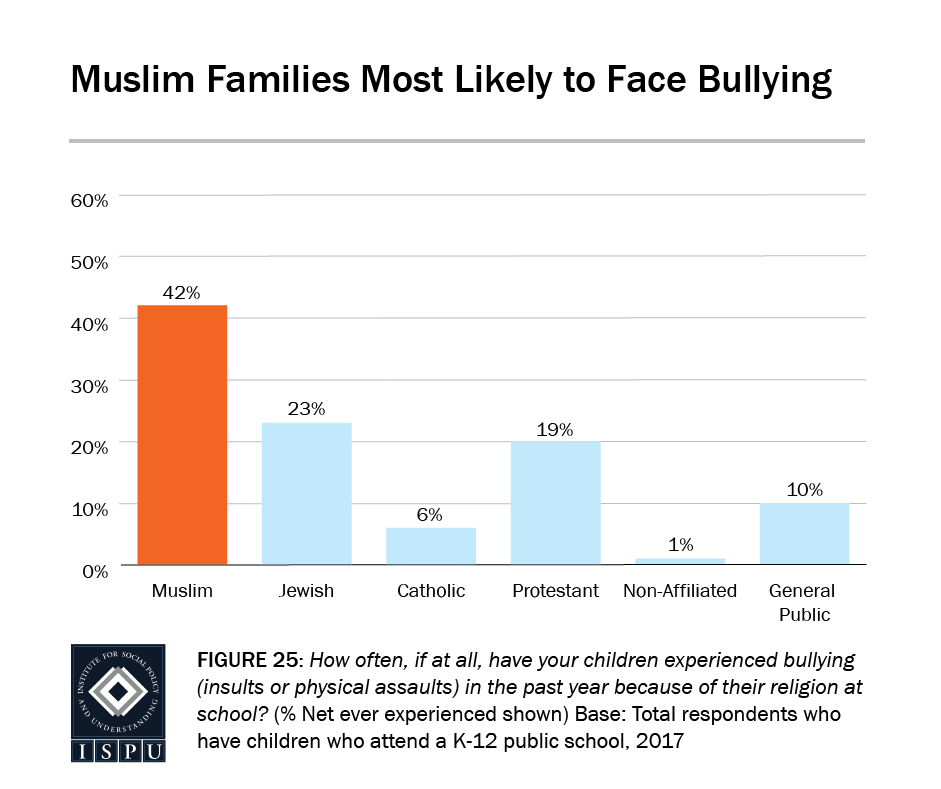

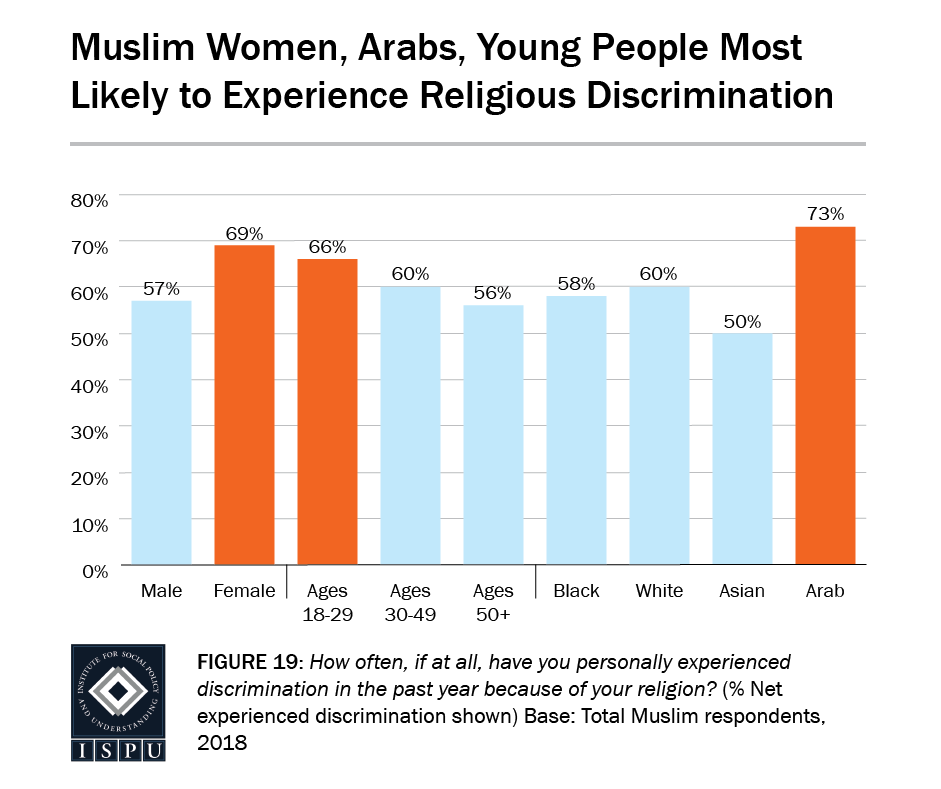

Data from ISPU’s American Muslim Poll: Muslims at the Crossroads shows that American Jews and Muslims disproportionately feel the negative effects of the United States’ political climate, including increased anxiety and instances of religious- and race-based discrimination. These two communities are the most likely of any faith group polled to say they fear for their safety from white supremacist groups as a result of the 2016 elections (27% of Jews and 38% of Muslims). Jewish and Muslim Americans are also the most likely to report experiencing religious discrimination (60% of Muslims and 58% of Jews). Children suffer, too—nearly a quarter of American Jewish families and more than 40% of American Muslim families report bullying of their kids in school because of their faith.

10.

Rather Than a Humanizing Profile of the Shooter, Center Your Stories on the Victims.

The quest for notoriety is a well-known motivator in instances of mass violence. Don’t provide it. Instead, feature the stories of those we lost—their hobbies, families, childhood, and passion for service or missions, if relevant. While it is important to understand the motivation of the shooter, humanizing childhood profiles are both offensive and risk inspiring copycat attacks. This time and space should instead be devoted to their victims.

Understanding Shariah

Shariah in Five Words

ISPU asked Dr. Asifa Quraishi-Landes, a trained Islamic legal expert and professor of law at the University of Wisconsin, for a five-word definition of shariah. Her answer: Shariah is “Islam’s recipe for a good life.” According to Quraishi-Landes:

- Shariah literally means “way” or “street.”

- In an Islamic context, the word shariah refers to the set of principles mandated by God through the Quran and Prophetic example.

- There is no one way to interpret and apply these principles. A rigorous legal process allows shariah to be interpreted in varying (and often contradictory/debated) ways in different times and contexts.

- Specific rulings that dictate Muslims’ lives are the result of this interpretation of shariah by Islamic jurists.

- This process, called ijtihad, produces rules called fiqh.

Shariah ≠ Islamic Law

According to Dr. Asifa Quraishi-Landes, translating shariah as “Islamic law” is problematic because in the United States, we think of law as derived and enforced by the state. However, religious law, like Jewish halakha or Islamic shariah, are often complete systems of doctrine that do not require state power to govern individual behavior.

What is Fiqh?

According to Quraishi-Landes: “Fiqh are Muslim rules of right action.”

- Fiqh rules cover a range of arenas, from religious rituals like prayer and fasting, to business transactions.

- Fiqh is pluralistic and is understood to be the unavoidably fallible, human articulation of shariah.

- Unfortunately, in some predominantly Muslim countries, one fiqh interpretation is codified into law and called “shariah.” This undermines the pluralism that is meant to exist among various schools of fiqh.

Dr. Asifa Quraishi-Landes conducts a brief overview of shariah. What is it? How is it related to secular law? How does it affect the lives of Muslims around the world?

SCHOLAR SPOTLIGHT:

Dr. Asifa Quraishi-Landes

ISPU Scholar, Professor of Law at University of Wisconsin Law School

Areas of Expertise: Comparative Islamic and U.S. constitutional law, American Muslims, civil liberties, U.S. politics, civil rights, religion, Muslims in the West

Shariah in an American Context

According to Islamic legal expert Dr. Asifa Quraishi-Landes:

- American Muslims’ request that the law recognize their choice to apply religious rules to their lives is not a demand that such rules be legislated for everyone.

- Muslims who bring up religious-based claims in American courtrooms are not attempting to change the prevailing secular law or force anyone else to follow shariah.

- Legal disputes involving the application of religious rules to the life of an American Muslim should be subject to the same constitutional scrutiny as any other contract.

- Judicial respect for shariah-based practices exemplifies how Americans value religious freedom and religious pluralism without discriminating between religions.

Shariah: Why the Term Matters to American Journalists

- So-called anti-shariah legislation restricts Muslims’ constitutional rights and religious freedoms by limiting the practice of their faith in personal legal matters.

- An aggressive anti-Muslim campaign has posited that shariah is “creeping” into American law and is a threat to American democracy. However, such claims from anti-Muslim activists and pseudo-experts sorely miss the mark.

- Moreover, though anti-Muslim legislation may be motivated by Islamophobia, there is evidence that these laws are strongly linked to other forms of bigotry and a legislative agenda aimed at excluding various minority communities from the political landscape.

- Data from over 3100 bills across all 50 U.S. states showed that anti-Muslim legislation and anti-Muslim bigotry frequently overlapped with prejudices directed toward other communities.

ISPU’s Islamophobia 2050 Restrictive Measures Map shows that (1) lawmakers that target Muslims also often support laws that disproportionately harm other marginalized communities and (2) such laws adversely affect communities of color, and others according to their national origin/ethnicity, civic association, gender, or sexual identity.

.

Women + Gender Roles

Muslim Women in the Media

- American media has increasingly expanded its coverage of Muslim women, both in the United States and abroad.

- Yet, representations of Muslim women often falsely stereotype them as meek, powerless, oppressed, or, after 9/11, as sympathetic to crime and violence or only relevant in the context of their headscarf.

- Such stereotypes not only contribute to negative perceptions of Muslim women in the U.S. but also fly in the face of actual data showing that American Muslim women overwhelmingly see their faith as an asset in their lives.

- So, too, reporting often falls short of explaining the diversity of Muslim women, both those born in America and others from dozens of countries.

American Muslim Women by the Numbers

ISPU’s data helps paint a more accurate, nuanced portrait of American Muslim women.

- In the United States, Muslim women are more diverse than women of other faiths and are from the only faith group with no majority race.

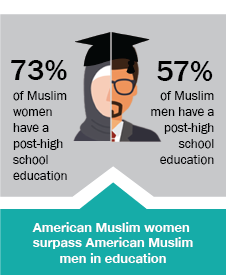

- American Muslim women are more likely to report higher socio-economic and educational status than their male counterparts.

American Muslim Women: Resilience Despite Challenges

- American Muslim women are also more likely than their male counterparts to say they experience discrimination and fear for their personal safety.

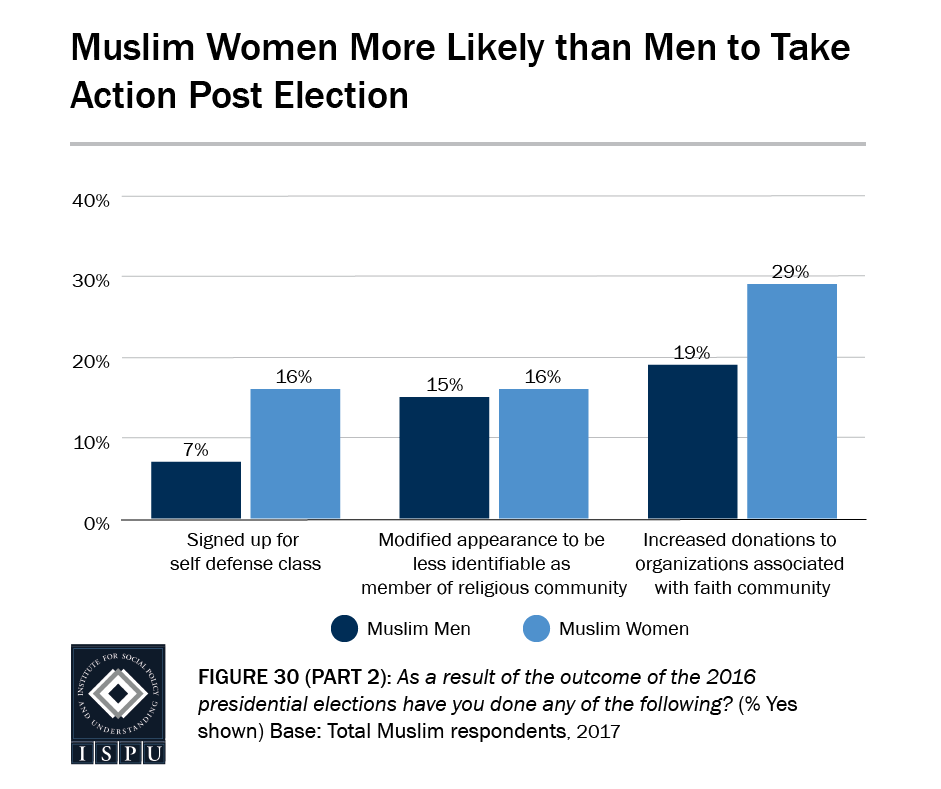

- Despite this, women are no more likely than men to alter their appearance to be less identifiably Muslim and have responded to the challenges they face with resilience and resistance.

- Additionally, American Muslim women value their religion as much as, if not more, than Muslim men, and are as active as men in their faith communities.

- Lastly, by an overwhelming margin, Muslim women choose how they should dress.

Muslim Women in the Media: A Closer Look

What characterizes representations of Muslim women in the media? How does this compare to representations of non-Muslim women? A recent, large-scale study of New York Times and Washington Post coverage of Muslim and non-Muslim women in foreign countries between 1980 and 2014 suggests the following:

MUSLIM WOMEN

⇢ More likely to appear in stories about societies with poor records of women’s rights

⇢ Coverage reduced to issues specific to gender inequality at the expense of other issues

NON-MUSLIM WOMEN

⇢ More likely to appear in stories about societies where their rights are respected

⇢ Presented with greater complexity

- U.S. news media’s tendency to frame coverage of women in Muslim societies around gender discrimination holds even after controlling for the actual conditions of women in those societies.

- Thus, countries with relatively good records of women’s rights are still more likely to be covered in relation to issues of gender inequality.

- The study concludes that slanted media coverage may be to blame for negative public opinion about Muslim women in the United States.

“U.S. media consumers are fed a particularly pernicious stereotype of Muslims: that they are distinctly sexist and misogynistic. This paints Muslims as a cultural threat to Western values. Since most Americans do not have direct contact with Muslims in their daily lives, media seriously influences public attitudes about Islam.”

– Dr. Rochelle Terman, postdoctoral fellow at the Center for International Security and Cooperation at Stanford University

.

Additional Resources

ISPU knows that media matters, and we are committed to helping journalists and media professionals do their best work.

Stay in touch with us on Facebook and Twitter.

More Information

You can browse ISPU’s list of expert scholars or turn to ISPU’s library of reports, case studies, and briefings for resources on:

- Civil liberties and Human Rights

- Demographics and Diversity

- Economic Development

- Entrepreneurship

- Gender and Identity

- Health and Social Development

- Immigration

- Islamophobia

- Law and Criminal Justice

- National Security

- Organizations and Institutions

- Refugee Policy

- Youth

- And more…

.

Research Team + Advisors

Marwa Abdalla

Author

MA candidate in Communication, San Diego State University

Dalia Mogahed

ISPU Director of Research

Katherine Coplen

ISPU Senior Communication Manager

Katie Grimes

ISPU Communication & Creative Media Specialist

Hannah Allam

Advisor

National reporter for BuzzFeed News, covering U.S. Muslim life. She previously spent a decade as a foreign correspondent at McClatchy, serving as Baghdad bureau chief during the Iraq War and Cairo bureau chief during the Arab Spring uprisings. She has also reported extensively on national security and race/demographics

Stephen Franklin

Advisor

Pulitzer Prize finalist, a former foreign correspondent, author and university instructor. He helped write and create “Islam for Journalists and Everyone Else.” He has trained journalists in Africa, the Arab world and South Asia.

Corey Saylor

Advisor

Managing Director of the Security and Rights Collaborative at ReThink Media; expert in political communications, media relations, and anti-Islam prejudice in the United States

.

Sources

Aaronson, Trevor. The Terror Factory: Inside the FBI’s Manufactured War on Terrorism. Brooklyn, NY: Ig Publishing, 2013.

Abdelkader, Engy. “Using the Legacy of Muslim Women Leaders to Empower.” Institute for Social Policy and Understanding, August 12, 2017.

Ali, Wajahat. “Top 30 Dos and Don’ts When Covering Islam and Muslims.” Religion Communicators Council. Accessed August 2018.

Ali, Yaser. “Shariah and Citizenship: How Islamophobia Is Creating a Second-Class Citizenry in America.” California Law Review 100, no. 4 (2012).

Aziz, Sahar. The Muslim “Veil” Post-9/11: Rethinking Women’s Rights and Leadership. Institute for Social Policy and Understanding, 2012.

Bleich, Erik, and A. Maurits van der Veen. “Newspaper Coverage of Muslims Is Negative. And It’s Not Because of Terrorism.” Washington Post, December 20, 2018.

Chouhoud, Youssef. “Who Thinks Muslim Leaders Should Condemn Terrorism?.” Institute for Social Policy and Understanding, January 24, 2018.

Corman, Steven R. “Why Some Some Islamists Are Violent and Others Aren’t.” Center for Strategic Communication, Arizona State University, May 25, 2010.

Esposito, John L., ed. The Oxford Dictionary of Islam. Oxford Islamic Studies Online, 2018.

Federal Bureau of Investigation (FBI). “What We Investigate: Terrorism.” Accessed August 2018.

Hauslohner, Abigail, Joel Achenbach, and Ellen Nakashima. “Investigators Said They Killed for ISIS. But Were They Different from ‘regular’ Mass Killers?.” Washington Post, September 23, 2016.

History Detectives. “Islam in America.” PBS. Accessed August 16, 2018.

Ibrahim, Noor. “Sheltering Muslim Domestic Violence Survivors.” The American Prospect, February 9, 2018.

Institute for Social Policy and Understanding, “Islamophobia 2050 Restrictive Measures Map,” 2018.

Islamic Networks Group. “Answers to Frequently Asked Questions about Muslims.” Accessed August 2018.

Karam, Rebecca. An Impact Report of Muslim Contributions to Michigan. Institute for Social Policy and Understanding, 2017.

Khan, Saeed, and Alejandro Beutel. Manufacturing Bigotry: A State-by-State Legislative Effort to Pushback Against 2050 by Targeting Muslims and Other Minorities. Institute for Social Policy and Understanding, 2014.

Lagasse, Paul, and Columbia University. The Columbia Encyclopedia. 8th ed. Columbia University Press, 2018.

Lari, Waliya. “Seven Ways to Avoid Double Standard Reporting on Extremist Violence.” Asian American Journalists Association, 2018.

Lipka, Michael. “How Many People of Different Faiths Do You Know?.” Pew Research Center, July 17, 2014.

Marthoz, Jean-Paul. Terrorism and the Media: A Handbook for Journalists. United Nations Educational, Scientific and Cultural Organization, 2017.

Media Tenor. “U.S. TV Primetime News Prefers Stereotypes: Muslims Framed Mostly as Criminals.” November 21, 2013.

Mogahed, Dalia, and Youssef Chouhoud. American Muslim Poll 2017: Muslims at the Crossroads. Institute for Social Policy and Understanding, 2017.

Mohamed, Besheer. “A New Estimate Shows U.S. Muslim Population Continues to Grow.” Pew Research Center, January 3, 2018.

Muslim Public Affairs Council. Not Qualified: Exposing the Deception Behind America’s Top 25 Pseudo Experts on Islam. Washington, DC: Muslim Public Affairs Council, 2013.

Parrott, Justin. Jihad as Defense: Just-war Theory in the Quran and Sunnah. Yaqeen Institute for Islamic Research, 2016.

Pew Research Center. “The World’s Muslims: Religion, Politics, Society.” April 30, 2013.

Quraishi-Landes, Asifa. “How Anti-Shariah Marches Mistake Muslim Concepts of State and Religious Law.” Religion News Service, June 8, 2017.

Quraishi-Landes, Asifa. Secular Is Not Always Better: A Closer Look at Some Women Empowering Features of Islamic Law. Institute for Social Policy and Understanding, 2013.

Quraishi-Landes, Asifa. Shariah and Diversity: Why Some Americans are Missing the Point. Institute for Social Policy and Understanding, 2013.

Quraishi-Landes, Asifa. Understanding Sharia in an American Context. Institute for Social Policy and Understanding, 2011.

Rao, Kumar, and Carey Shenkman, Equal Treatment? Measuring the Media and Legal Responses to Ideologically Motivated Violence in the United States. Institute for Social Policy and Understanding, 2018.

Shane, Scott. “Homegrown Extremists Tied to Deadlier Toll Than Jihadists in U.S. Since 9/11.” New York Times, June 24, 2015.

Suleiman, Imam Omar, and Dr. Nazir Khan. Playing the Taqiyya Card: Evading Intelligent Debate by Calling All Muslims Liars. Yaqeen Institute for Islamic Research, 2017.

Terman, Rochelle E. “Islamophobia and Media Portrayals of Muslim Women: A Computational Text Analysis of U.S. News Coverage.” International Studies Quarterly. Accessed August 16, 2018.

Terman, Rochelle. “The News Media Offer Slanted Coverage of Muslim Countries’ Treatment of Women.” Washington Post, May 5, 2017.

Younis, Mohamed. “Muslim Americans Exemplify Diveristy, Potential.” Gallup, March 2, 2009.