.

American Muslim Poll 2019

Predicting and Preventing Islamophobia

MAY 1, 2019 | BY DALIA MOGAHED AND AZKA MAHMOOD

SUMMARY

ISPU’s fourth annual poll informs national conversations with the voices of everyday Americans. Researchers, policymakers, and the public have access to key insights and analysis into the attitudes and policy preferences of American Muslims, Jews, Catholics, Protestants, white Evangelicals, the non-affiliated, and the general public. For the second year, in partnership with the Georgetown University’s The Bridge Initiative, we track The National Islamophobia Index, measuring how much the public endorses anti-Muslim tropes. New this year: Our researchers examine protective factors against Islamophobia, as well as data-driven recommendations for those working to elevate American Muslim civic engagement and for those combating anti-Muslim bigotry.

.

Introduction

Triumphs and tribulations punctuated the year leading up to ISPU’s fourth annual poll of American religious communities. In June 2018, the Supreme Court upheld a fourth iteration of the travel ban, which allows vast immigration restrictions for travelers from Iran, Libya, North Korea, Somalia, Syria, Venezuela, and Yemen. Five of these seven nations are majority Muslim. In their scathing dissent of the majority decision, Justices Sonia Sotomayor and Ruth Bader Ginsburg said the ruling “leaves undisturbed a policy first advertised openly and unequivocally as a ‘total and complete shutdown of Muslims entering the United States’ because the policy now masquerades behind a façade of national-security concerns.”

Later that year, Ilhan Omar, a hijab-wearing former refugee originally from Somalia, and Rashida Tlaib, a Palestinian American, were the first Muslim women elected to the U.S. House of Representatives, each taking her oath on her personal Quran.

Analysts have credited the record-breaking voter turnout of the 2018 midterms for bringing Omar and Tlaib to Congress in an election that saw a number of “firsts,” mostly Democratic women of color and LGBTQ individuals. These Freshman lawmakers make up a new class of members of Congress who ran on some of the most progressive and anti-establishment platforms seen in years, and gave Democrats a majority in the House.

This new Congress witnessed the longest government shutdown in history (lasting from December 22, 2018, to January 25, 2019) over President Donald Trump’s demand for $5 billion to complete a wall on the U.S.-Mexico border, leaving large swaths of the American public without income for five weeks.

As women shattered the glass ceiling of Congress in record numbers, the #MeToo movement continued to race forward, bringing attention to sexual misconduct long normalized and left unacknowledged in the corporate sector, media, and government. It also brought attention to sexual misconduct within religious communities. This includes the Muslim community, where a new grassroots organization called FACE (Facing Abuse in Community Environments) began to investigate and document cases of alleged abuse in an effort to raise awareness and demand accountability.

It was against this backdrop that ISPU conducted its fourth annual 2019 poll of American faith and non-faith groups.

How were Americans of varying faith backgrounds feeling about the direction of the country in the midst of a government shutdown? In a year where voter turnout broke records, how likely were Americans who are Muslim to participate in the midterm election compared to other groups? More importantly, what factors predict their participation? Does a candidate’s support for the so-called Muslim ban help or hurt their run for public office? And with whom do Muslims find the greatest political common ground? How common are unwanted sexual advances from a faith leader in each religious community? And how likely is it that these alleged transgressions are reported to law enforcement or community leadership?

We also continue our annual measure of the Islamophobia Index with the Bridge Initiative, a measure of the level of public endorsement of anti-Muslim tropes. Have levels of Islamophobia in America increased, decreased, or stayed the same? Last year we examined the impact of Islamophobia on society, discovering that higher levels of anti-Muslim sentiment are linked to greater acceptance of violence against civilians, authoritarian policies, and anti-Muslim discrimination. This year, we sought to explore the drivers of Islamophobia. What predicts lower or higher anti-Muslim views? And with whom do Muslims find the greatest support?

We conclude our study with a set of data-driven recommendations for those working to elevate American Muslim civic engagement and for those combating Islamophobia. In light of the horrific massacre of 50 worshippers in a mosque in Christchurch, New Zealand, on March 15, 2019, by a man reciting every anti-Muslim trope in our index, these recommendations seem ever more urgent.

We hope this report continues to inform our national conversation with the voices of ordinary people.

DOWNLOADS

MORE ANALYSIS

Not Immune: Some Muslims in America Internalize Islamophobia

Unwanted Sexual Advances from Faith Leaders Are Equally Prevalent Across Faith Groups

Muslims Profess More Private Religious Devotion, Less Public Religious Assertiveness

The Majority of Muslims Believe Poverty Is the Result of Bad Circumstances, Not Bad Character

To Have and to Hold, Part Two: Interracial Marriage among American Muslims

SUMMARY

ISPU’s fourth annual poll informs national conversations with the voices of everyday Americans. Researchers, policymakers, and the public have access to key insights and analysis into the attitudes and policy preferences of American Muslims, Jews, Catholics, Protestants, white Evangelicals, the non-affiliated, and the general public. For the second year, in partnership with the Georgetown University’s The Bridge Initiative, we track The National Islamophobia Index, measuring how much the public endorses anti-Muslim tropes. New this year: Our researchers examine protective factors against Islamophobia, as well as data-driven recommendations for those working to elevate American Muslim civic engagement and for those combating anti-Muslim bigotry.

DOWNLOADS

Introduction

Triumphs and tribulations punctuated the year leading up to ISPU’s fourth annual poll of American religious communities. In June 2018, the Supreme Court upheld a fourth iteration of the travel ban, which allows vast immigration restrictions for travelers from Iran, Libya, North Korea, Somalia, Syria, Venezuela, and Yemen. Five of these seven nations are majority Muslim. In their scathing dissent of the majority decision, Justices Sonia Sotomayor and Ruth Bader Ginsburg said the ruling “leaves undisturbed a policy first advertised openly and unequivocally as a ‘total and complete shutdown of Muslims entering the United States’ because the policy now masquerades behind a façade of national-security concerns.”

Later that year, Ilhan Omar, a hijab-wearing former refugee originally from Somalia, and Rashida Tlaib, a Palestinian American, were the first Muslim women elected to the U.S. House of Representatives, each taking her oath on her personal Quran.

Analysts have credited the record-breaking voter turnout of the 2018 midterms for bringing Omar and Tlaib to Congress in an election that saw a number of “firsts,” mostly Democratic women of color and LGBTQ individuals. These Freshman lawmakers make up a new class of members of Congress who ran on some of the most progressive and anti-establishment platforms seen in years, and gave Democrats a majority in the House.

This new Congress witnessed the longest government shutdown in history (lasting from December 22, 2018, to January 25, 2019) over President Donald Trump’s demand for $5 billion to complete a wall on the U.S.-Mexico border, leaving large swaths of the American public without income for five weeks.

As women shattered the glass ceiling of Congress in record numbers, the #MeToo movement continued to race forward, bringing attention to sexual misconduct long normalized and left unacknowledged in the corporate sector, media, and government. It also brought attention to sexual misconduct within religious communities. This includes the Muslim community, where a new grassroots organization called FACE (Facing Abuse in Community Environments) began to investigate and document cases of alleged abuse in an effort to raise awareness and demand accountability.

It was against this backdrop that ISPU conducted its fourth annual 2019 poll of American faith and non-faith groups.

How were Americans of varying faith backgrounds feeling about the direction of the country in the midst of a government shutdown? In a year where voter turnout broke records, how likely were Americans who are Muslim to participate in the midterm election compared to other groups? More importantly, what factors predict their participation? Does a candidate’s support for the so-called Muslim ban help or hurt their run for public office? And with whom do Muslims find the greatest political common ground? How common are unwanted sexual advances from a faith leader in each religious community? And how likely is it that these alleged transgressions are reported to law enforcement or community leadership?

We also continue our annual measure of the Islamophobia Index with the Bridge Initiative, a measure of the level of public endorsement of anti-Muslim tropes. Have levels of Islamophobia in America increased, decreased, or stayed the same? Last year we examined the impact of Islamophobia on society, discovering that higher levels of anti-Muslim sentiment are linked to greater acceptance of violence against civilians, authoritarian policies, and anti-Muslim discrimination. This year, we sought to explore the drivers of Islamophobia. What predicts lower or higher anti-Muslim views? And with whom do Muslims find the greatest support?

We conclude our study with a set of data-driven recommendations for those working to elevate American Muslim civic engagement and for those combating Islamophobia. In light of the horrific massacre of 50 worshippers in a mosque in Christchurch, New Zealand, on March 15, 2019, by a man reciting every anti-Muslim trope in our index, these recommendations seem ever more urgent.

We hope this report continues to inform our national conversation with the voices of ordinary people.

.

In January 2019, the Institute for Social Policy and Understanding conducted a survey of American Muslims, Jews, Catholics, Protestants, including white Evangelicals, and the non-affiliated, to examine their views on politics, religion, sexual and religious violence, minorities, and other faith groups. Our findings show that American Muslims are multi-dimensional; they share many characteristics with other faith groups and non-affiliated Americans and, yet, are unique. They are disappointed with some aspects of their country and express hope in others.

American Muslims are multi-dimensional; they share many characteristics with other faith groups and non-affiliated Americans and, yet, are unique. They are disappointed with some aspects of their country and express hope in others.

Muslims Least Likely to Approve of President but More Likely to Express Optimism with the Direction of the Country

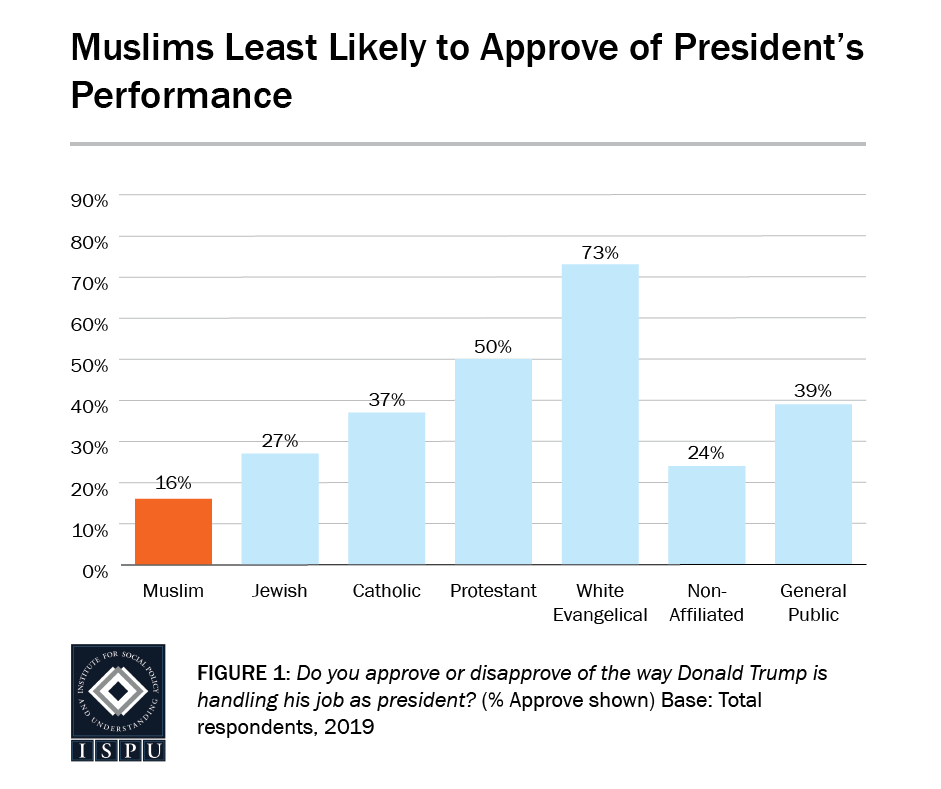

We found that only 16% of American Muslims approve of the job Donald Trump is doing as President, the lowest of all groups surveyed. While other groups tallied between 24% and 50%, the majority of white Evangelicals (73%) reported approval of the President and highlighted a deep rift between the two religious groups. Among Muslims, white Muslims (29%) and those who are 30-49 years old (19%) are more likely to approve of Donald Trump than all others.

Despite the low opinion of the performance of the President, 33% of Muslims conveyed optimism about the future trajectory of the nation, more than any other faith group or unaffiliated Americans surveyed. While white Muslims (43%) are more likely than Black Muslims (20%) to be upbeat, Muslim women (70%) are more likely than Muslim men (58%) to be pessimistic about the future. We find Muslims’ overall positivity remarkable given the fact that all other groups surveyed registered a sharp decline in their satisfaction with the way things are going in the country. We posit that Muslim and Democratic gains in the 2018 midterm elections and the continued resistance to Trump’s anti-immigration policies are responsible for Muslims’ confidence.

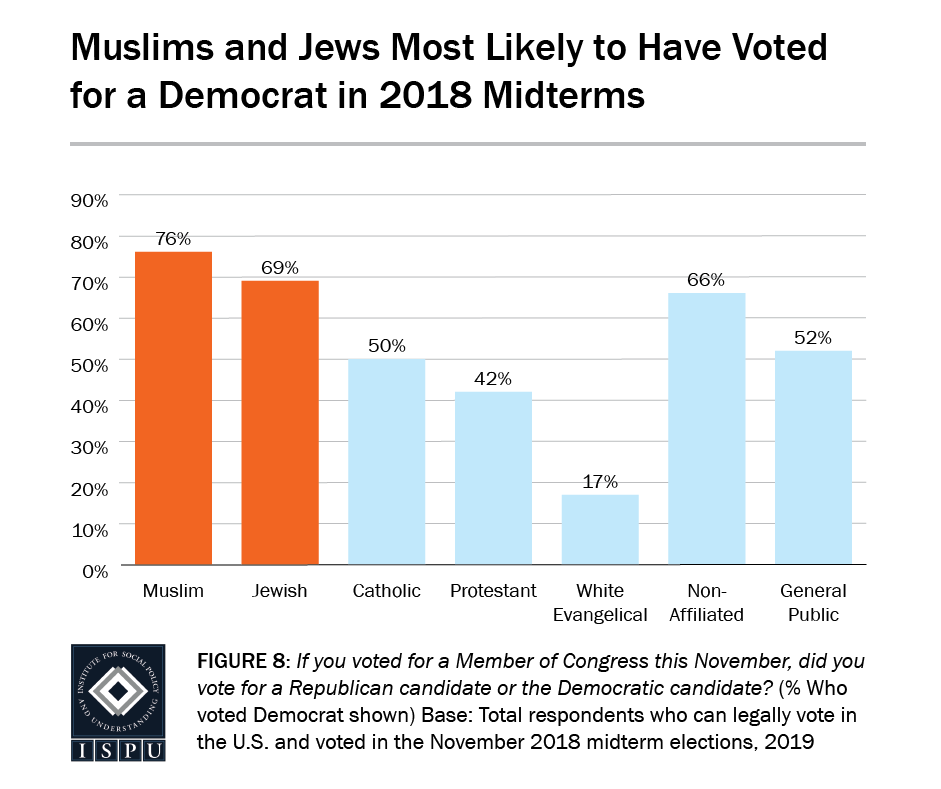

Muslims Who Vote Overwhelmingly Favor Democrats

Our findings show that Muslims directed their frustration with the administration at the polls and voted overwhelmingly in favor of Democratic candidates. Three-quarters of Muslims (76%) cast their ballots for Democrats, a trend mirrored among the Jewish Americans (69%) we surveyed, as well as Black (91%) and Hispanic Americans (66%) more generally. Among Muslims, support for Democrats remains consistent with age as opposed to the general public where it decreases: 83% of Muslims aged 50 and older vote for Democrats in contrast with 44% of their generational peers in the general public.

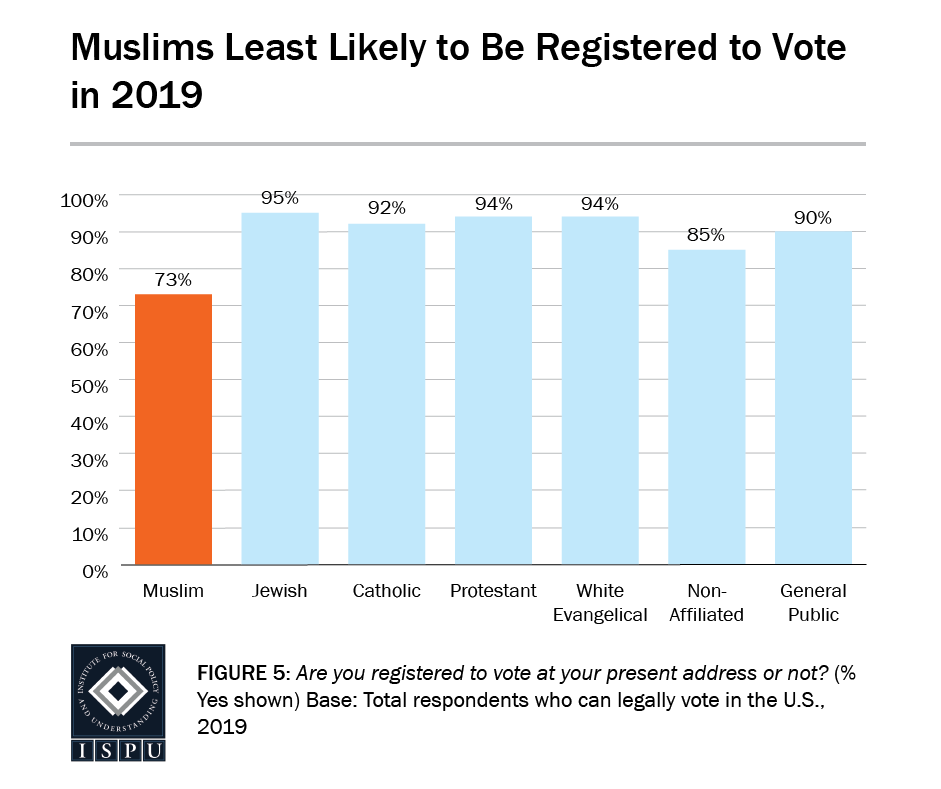

Though Growing, Muslim Voter Registration and Engagement Still Lags Behind Other Groups

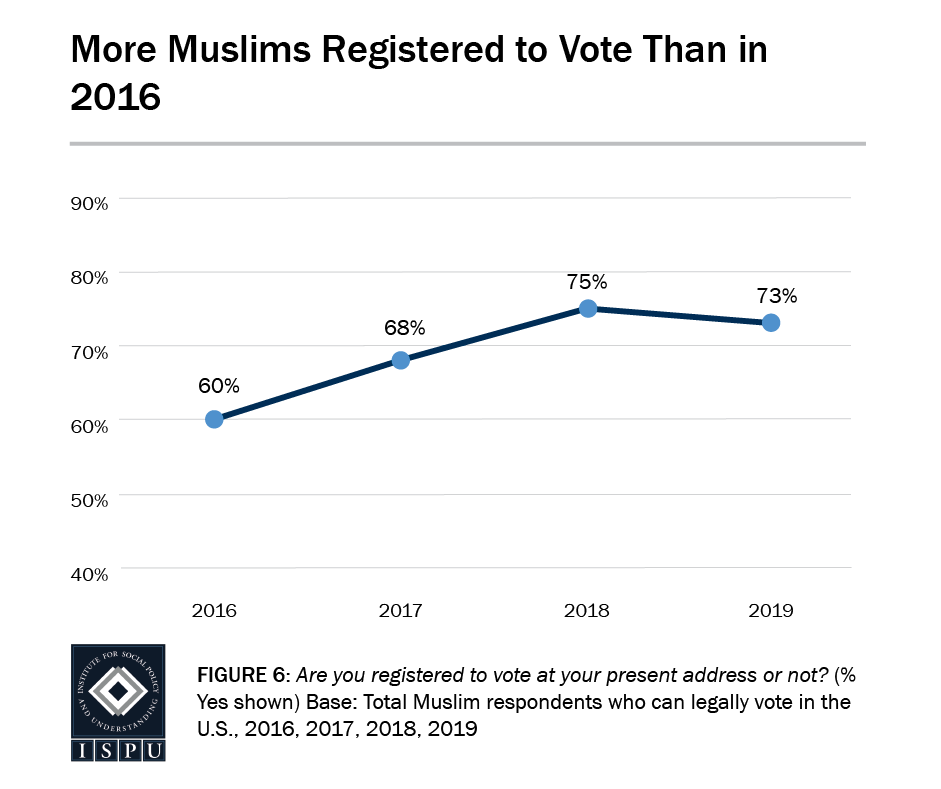

Despite being higher than in 2016 (60%), only 73% of eligible Muslim voters report being registered to do so, the least likely in our 2019 sample (85%-95%). [1] Overall, Muslims’ voter eligibility is 80%, which is less than the other groups in our survey and this gap may persist because 47% of American Muslims are not native-born. The voter registration gap is most pronounced among Muslim young adults (aged 18-29), only 63% of whom report being registered to vote compared to 85% of their peers in the general population. Muslim voter engagement further suffers due to the inconsistency of Muslim voters who express their intentions to vote (83%) but show up at the polls in fewer numbers (59%), either due to lack of choice of candidates or distrust in the electoral system. Despite these large gaps, Muslims contested in the 2018 midterm elections in unprecedented numbers, recording as many as 131 wins at local and state levels, and securing three Congressional positions.

The voter registration gap is most pronounced among Muslim young adults (aged 18-29), only 63% of whom report being registered to vote compared to 85% of their peers in the general population.

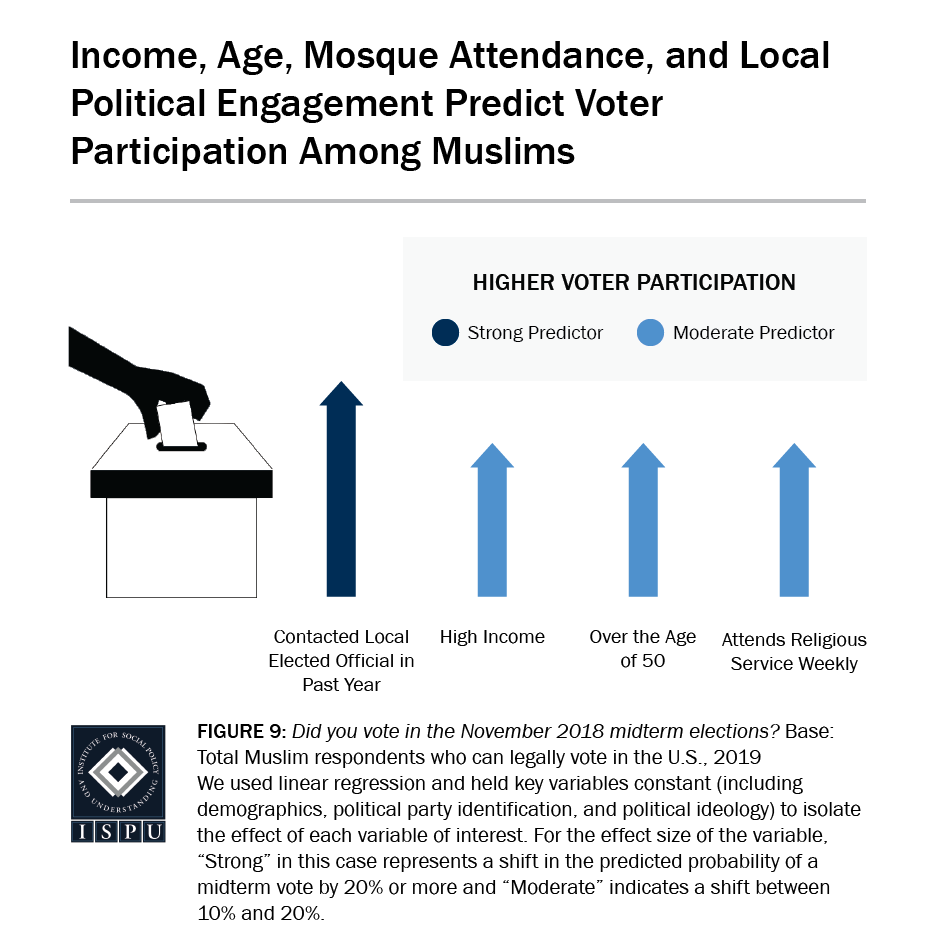

Muslim Local Engagement with Elected Officials a Predictor of Voter Participation More Broadly

We found that some expected factors such as higher income and older age, as well as religious attendance as previously reported in ISPU polls, hold true as predictors of voter participation for Muslims as they do for other Americans. However, in the case of Muslims, contacting a local elected official emerged as the single strongest determinant of voter participation. We also found that Muslims are the group least likely to communicate with local and federal elected officials, with only 21% of Muslim men and 20% of Muslim women reporting communication with a local official.

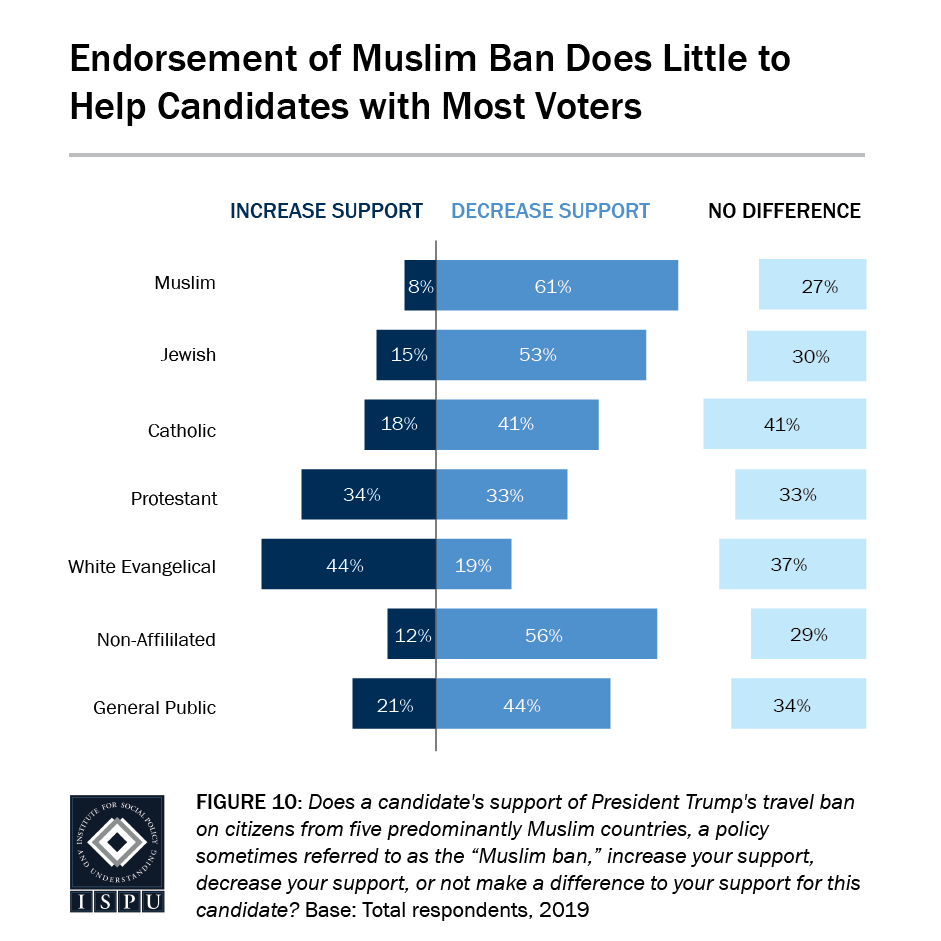

Support for Muslim Ban Does Little to Help Candidates with Most Voters

Sixty-one percent of Muslims, 53% of Jews, and 56% of non-affiliated Americans report that a candidate’s endorsement of the Muslim ban would decrease their support for that individual. While white Evangelicals (44%) are the most likely of any group to say a candidate’s endorsement of the Muslim ban would increase their support of that candidate, a majority of even this faith group saw the issue as either decreasing their support (19%) of such a candidate or making no difference (37%). The plurality of the general public (44%) say a candidate’s endorsement of a Muslim ban would decrease their support, while 21% say it would increase their support. Thirty-four percent of the general public say it would make no difference to them whether or not a candidate supported the Muslim ban.

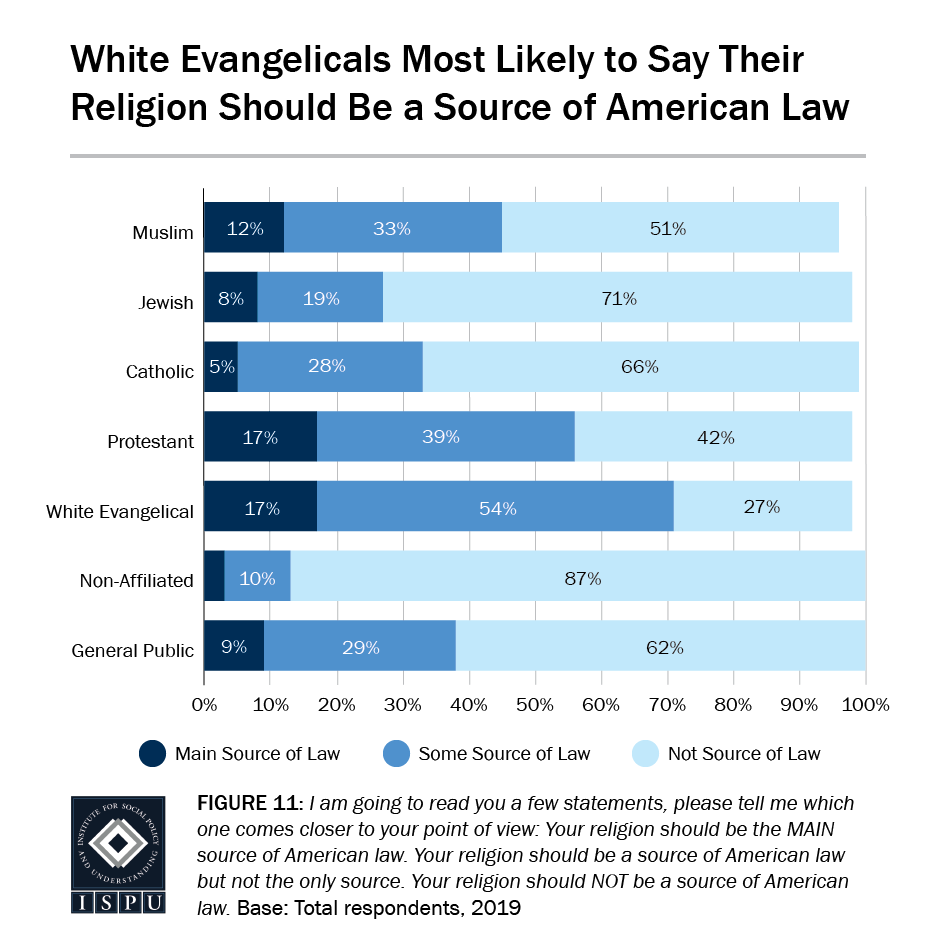

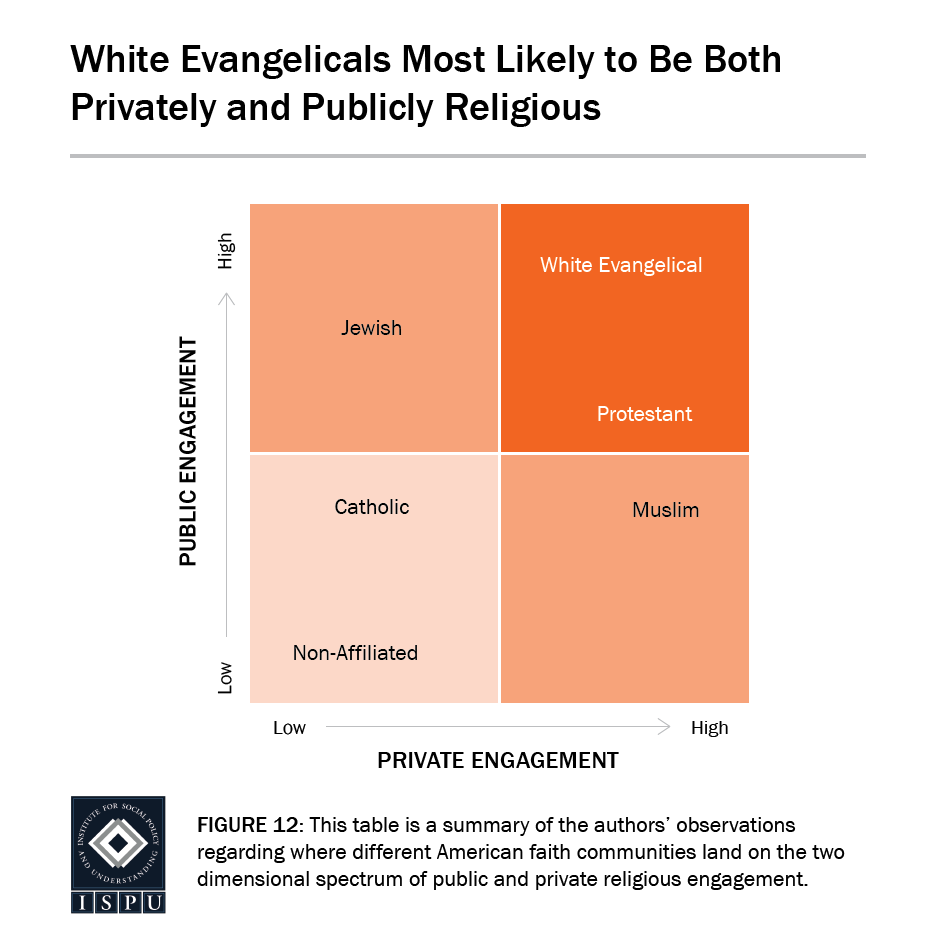

Muslims Profess More Private Religious Devotion, Less Public Religious Assertiveness

We found that Muslims (71%) and white Evangelicals (82%) are the most likely to say religion is very important in their daily life, more than all other faith groups and non-affiliated Americans. Despite facing higher levels of religious discrimination than other groups, Muslims hold steady to their faith. Forty-three percent of Muslims attend religious services once a week or more, on par with Protestants (49%) but less frequently than white Evangelicals (64%). More Muslims (78% of men and 79% of women) report satisfaction with the way things are done in their house of worship than the general public (62%).

Muslims are more likely to be privately devout—derive meaning and purpose from their faith (63%) and draw on their faith to forgive someone who has hurt them deeply (54%)—than all groups surveyed except white Evangelicals (75% and 63%).

However, Muslims are less likely to publicly assert their religious beliefs such as take unpopular stands to defend their faith (36%) or wish to use their faith as a source of law (33%) than white Evangelicals (58% and 54%). Muslims (55%) have a sense of linked fate, [2] that is, to believe that their fate is tied to that of their coreligionists, as much as Protestants (55%) and white Evangelicals (57%), but less than Jews (69%). Though it can be reasonably expected that greater personal spiritual engagement would translate into greater public assertion of faith, Muslims are highest on dimensions that reflect private spirituality and lower on the one that requires public risk, likely because of the threat of religious discrimination, which Muslims continue to report at higher frequencies (62%) than any other faith group (43% or less).

In comparison, white Evangelicals are high both on private and public dimensions of religiosity, with faith playing a central role in their personal lives as well as what they wish to see in their society. Jews are low on private measures of spiritual engagement such as frequency of religious services, but higher on public assertion of their faith identity and a sense of a linked fate with co-religionists.

Muslims Most Likely to Report Religious, Gender, and Sectarian Discrimination

As reported in our prior polls, Muslims are the most likely group to report experiencing religious discrimination (62%). Muslim women report higher levels of discrimination (68%) than men (55%). Second to Muslims, 43% of Jews report religious discrimination, while 36% of white Evangelicals report experiencing it. With 40% registering experiences of sectarianism, Muslims are the group most likely to have sectarian discrimination within their ranks as compared to other groups surveyed.

Our data show that 41% of Muslim women experience gender discrimination from within their community, the highest of any group examined. However, the misogyny they suffer from the public at large is still greater at 52%. Muslim women are also more likely to report gender discrimination from the public than are any other group of women surveyed (36% or less).

Though Unwanted Sexual Advances from a Faith Leader Equally Prevalent Across Communities, Muslims Most Likely Group to Report to Law Enforcement

Unwanted sexual advances from a faith leader are equally prevalent among all groups we surveyed. All groups are also equally likely to report such advances to members of the community. However, Muslim victims of sexual crimes are most likely to speak up against perpetrators and more likely (54%) to involve law enforcement in such matters than other groups in our study.

Islamophobia Index Inches Up

A measure of the level of public endorsement of five negative stereotypes associated with Muslims in America, our Islamophobia Index inched up from 24 in 2018 to 28 in 2019. The Islamophobia Index calculates reported levels of agreement with the following statements:

- Most Muslims living in the United States are more prone to violence than others.

- Most Muslims living in the United States discriminate against women.

- Most Muslims living in the United States are hostile to the United States.

- Most Muslims living in the United States are less civilized than other people.

- Most Muslims living in the United States are partially responsible for acts of violence carried out by other Muslims

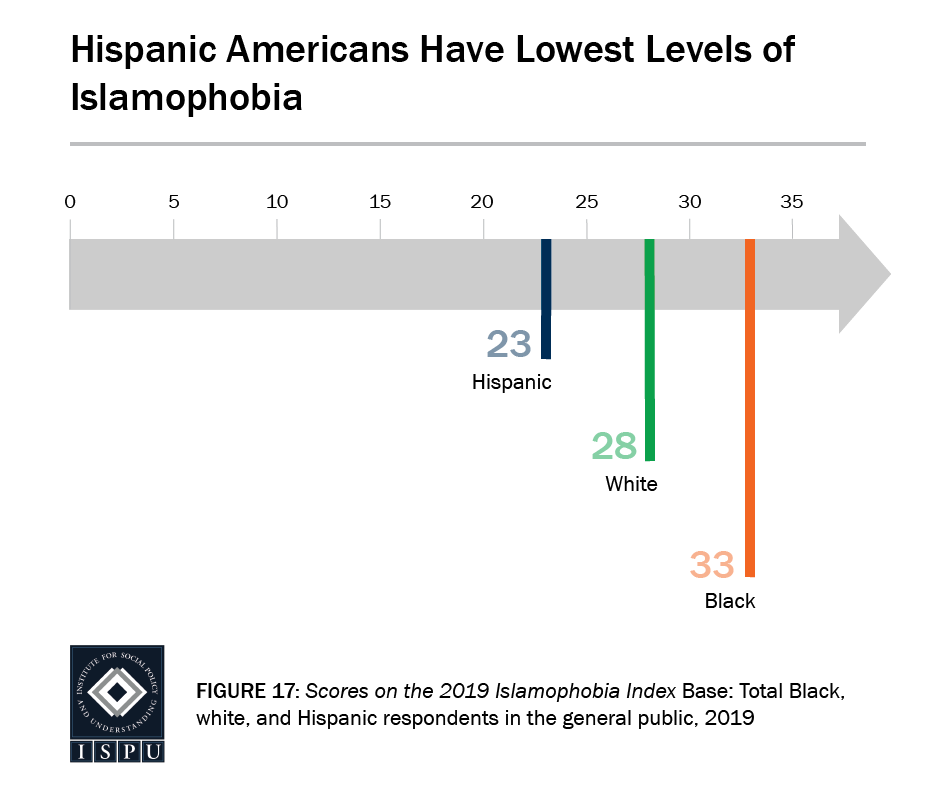

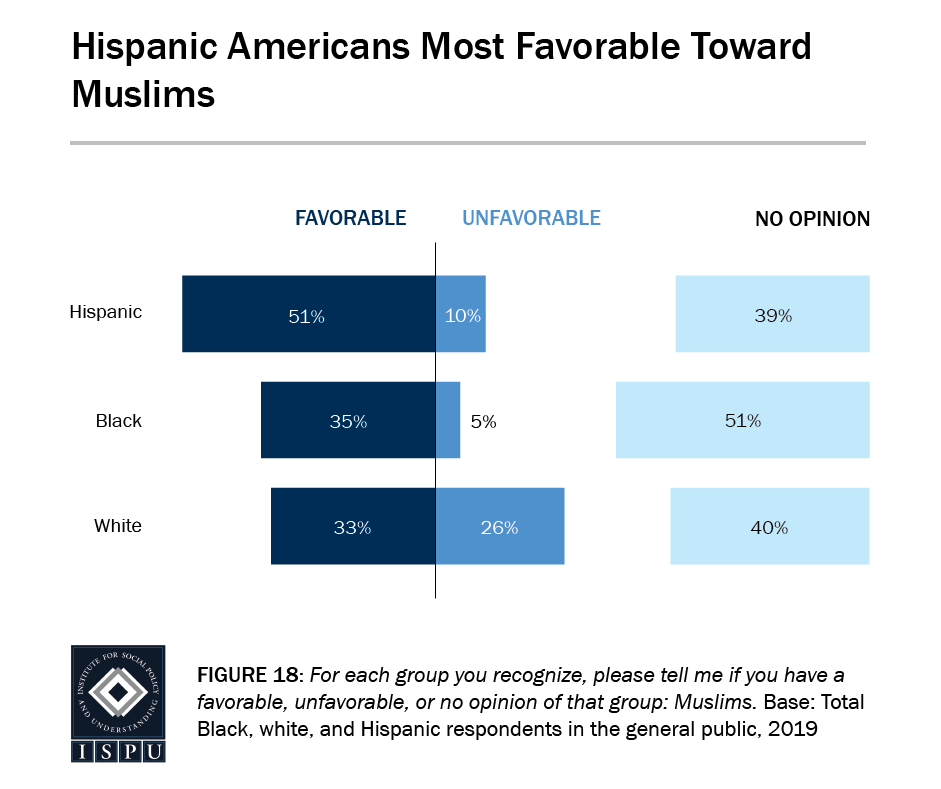

Jews and Hispanic Americans Are Most Favorable Toward Muslims and White Evangelicals Least

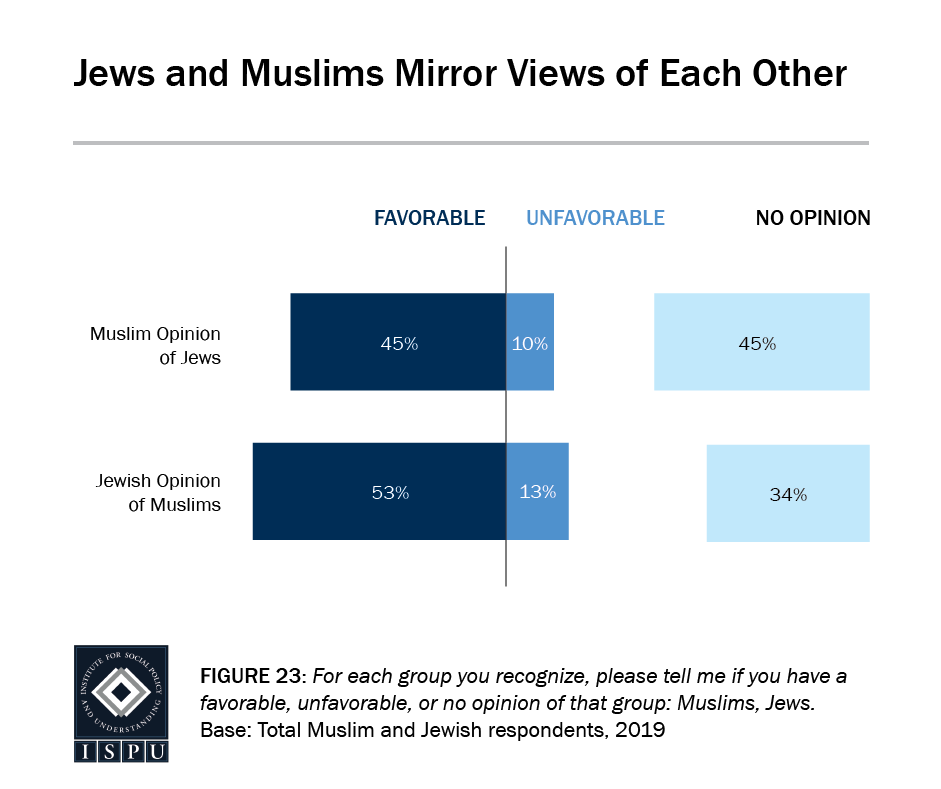

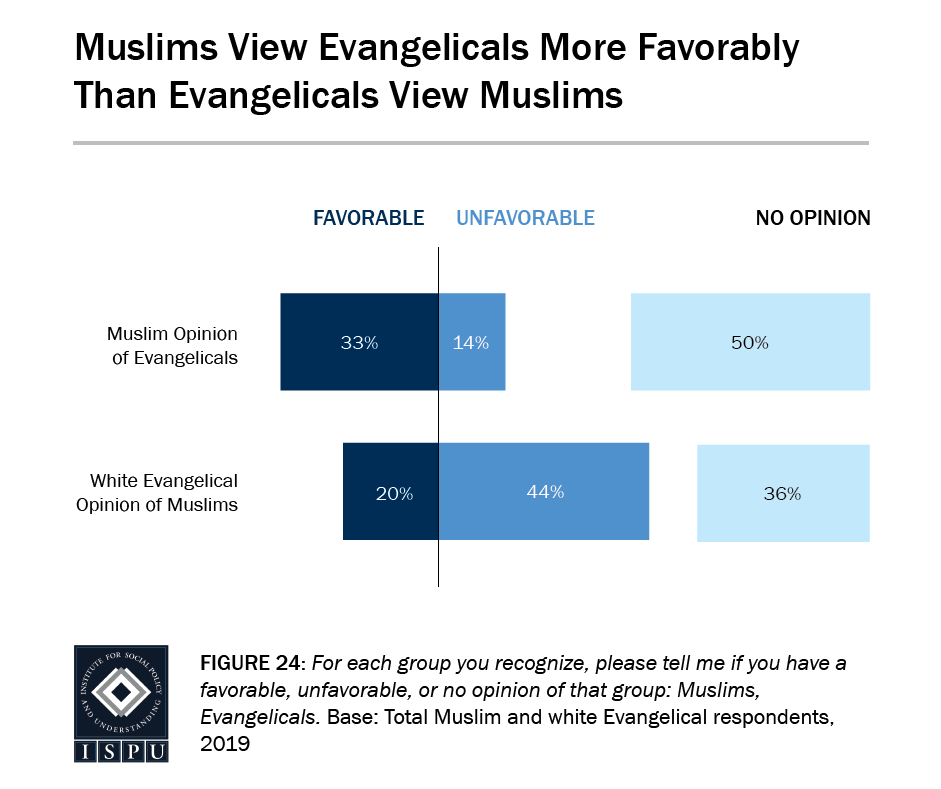

Of all faith groups apart from Muslims, Jews score the lowest on the Islamophobia Index. A majority (53%) of Jews report having positive views of Muslims with 13% reporting negative views. In contrast, white Evangelicals score the highest on the Islamophobia Index with as many as 44% holding unfavorable opinions about Muslims, which is twice as many as those who hold favorable opinions (20%).

Analyzed by race, Hispanic Americans are five times as likely to hold favorable opinions of Muslims as they are to have negative attitudes (51% vs. 10%). In comparison, white Americans are almost as likely to hold favorable as unfavorable opinions (33% vs. 26%), whereas 40% have no opinion. Black Americans are seven times as likely to hold positive opinions (35%) as negative views (5%) of Muslims, but the majority report having no opinion (51%).

Hispanic Americans are five times as likely to hold favorable opinions of Muslims as they are to have negative attitudes.

Knowing a Muslim Linked to Lower Islamophobia

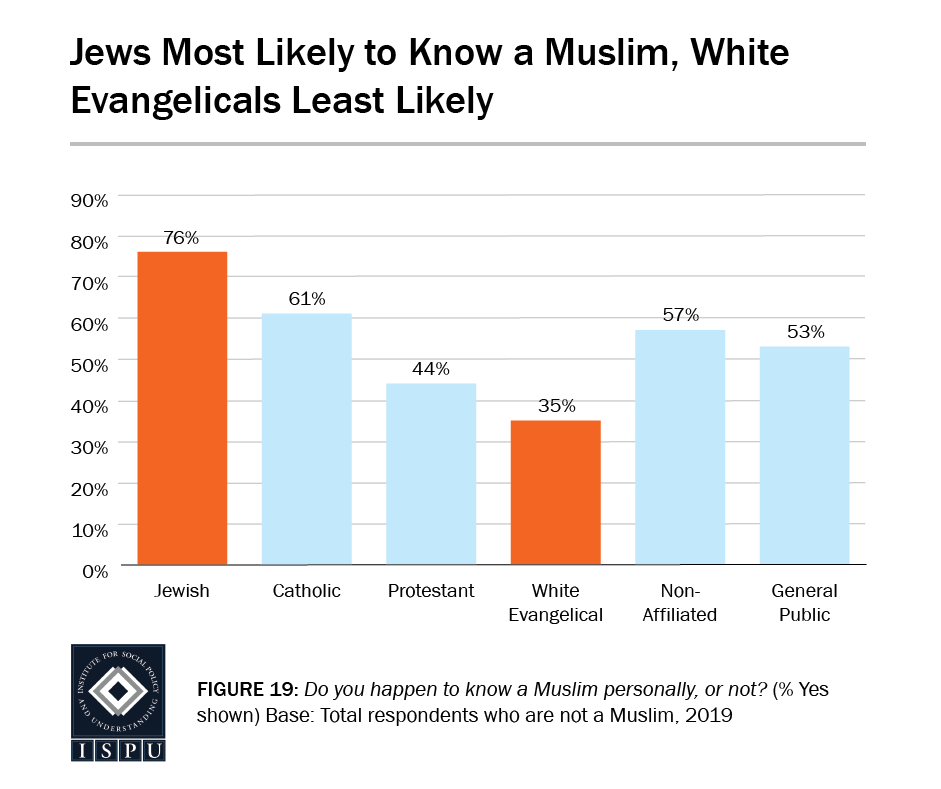

Our analysis reveals that knowing a Muslim personally is among several protective factors against Islamophobia. When a Muslim is a close friend, Islamophobia is further reduced. We found that three in four Jews know a Muslim, about half of the general public know a Muslim, but only about one in three among white Evangelicals know an American who is Muslim.

Other predictors of lower Islamophobia include Democratic leanings; knowledge about Islam; favorable views of Jews, Black Americans, and feminists; and higher income. To a lesser extent, negative views of Evangelicals are significantly linked to a lower score on the Islamophobia Index (less Islamophobia), though the correlation is weak. Notably, respondents’ nativity, sex, age, education, and religiosity have no bearing on Islamophobia.

Methodology

ISPU created the questionnaire for this study and commissioned Social Science Research Solutions (SSRS) to conduct a nationally representative survey of self-identified Muslims and Jews and a nationally representative survey of the general American public. Researchers examined the views of self-identified Protestants (parsing out white Evangelicals), Catholics, and the non-affiliated. White Evangelicals are routinely studied in religion survey research as a separate subgroup due to their unique social and political characteristics (see, for example, this survey by the Public Religion Research Institute [PRRI] and this study by the Pew Research Center). In our analysis, we make comparisons among age and racial groups. For race comparisons among the Muslim sample, we do not include Hispanic Americans in the racial comparisons due to small sample size. In the general public, we exclude Asian Americans due to small samples sizes. A total of 2,376 interviews were conducted. ISPU owns all data and intellectual property related to this study.

SSRS conducted the survey of Muslims, Jews, and the general population for ISPU from January 8-25, 2019. SSRS interviewed 804 Muslim and 360 Jewish respondents. The sample for the study came from multiple sources. SSRS telephoned a sample of households that were prescreened as being Muslim or Jewish in SSRS’s weekly national omnibus survey of 1,000 randomly selected respondents (n = 648) and purchased a listed sample for Muslim and Jewish households in both landline (from Experian) and cell phone (from Consumer Cell) samples, sample providers that flags specific characteristics for each piece of a sample (n = 133). In an effort to supplement the number of Muslim interviews that SSRS was able to complete in the given time frame and with the amount of available prescreened sample, SSRS employed a web-based survey and completed the final 383 Muslim subject interviews via an online survey with samples from a non-probability panel (a panel made up of respondents deliberately [not randomly] chosen to represent the demographic makeup of the community in terms of age, race, and socio-economics). SSRS used their sample in the probability panel to administer the general population portion of the survey (n = 1,108). These are respondents who have completed a survey through the SSRS omnibus and signed up for the probability panel. In an effort to balance out the general population probability panel, SSRS interviewed 104 non-Internet respondents through the omnibus survey, which uses a fully replicated, stratified, single-stage, random-digit-dialing (RDD) sample of landline telephone households and randomly generated cell phone numbers. Sample telephone numbers are computer-generated and loaded into online sample files accessed directly by the computer-assisted telephone interviewing (CATI) system.

For the Muslim and Jewish samples, the data are weighted to: 1) adjust for the fact that not all survey respondents were selected with the same probability, and 2) account for non-response across known demographic parameters for the Jewish and Muslim adult populations. The survey has a margin of error at a 95% confidence level of Muslims ±4.9% and Jews ±7.6%.

For the general population sample, the data are weighted to provide nationally representative and projectable estimates of the adult population 18 years of age and older. The weighting process takes into account the disproportionate probabilities of household and respondent selection due to the number of separate telephone landlines and cell phones answered by respondents and their households, as well as the probability associated with the random selection of an individual household member. The survey has a margin of error at a 95% confidence level of general population ±3.6%.

Click here for more details on polling methodology.

.

Civic Engagement

Muslims Least Likely to Approve of President and as Likely as Jews to Have Voted Democrat in the Midterms

Two years into the Trump presidency, American Muslims (16%) are the least likely group to report a favorable view of Donald Trump as President (Figure 1). Opinions about the current President have held broadly similar to those reported in our survey in 2018. On the whole, approval has inched up minimally higher across all groups but inter-group differences have held steady. Non-affiliated (24%) and Jewish (27%) sentiments are slightly more positive than Muslims’ (16%), yet on the lower end of the spectrum. Catholic views (37%) hover right around the general public average (39%), and Protestants’ are slightly higher (50%). By far and away, white Evangelicals (73%) are the group most likely to approve of the President. As in previous years, the data illustrate a schism between Muslims and white Evangelicals regarding the performance of Donald Trump as President.

Did You Know?

Every year, ISPU conducts this survey of American Muslims, Jews, Catholics, Protestants, and the non-affiliated. It’s the only poll of its kind, offering the latest trends and demographic data on American Muslims. And every year, we rely on individuals like you to keep this research free and accessible to all. Right now, we need your help to keep it that way, so that millions can remain informed on the topics that matter the most. If you value the reliable data our poll provides, consider making a donation—big or small—in support of ISPU’s American Muslim Poll 2020. It only takes a minute. Thank you.

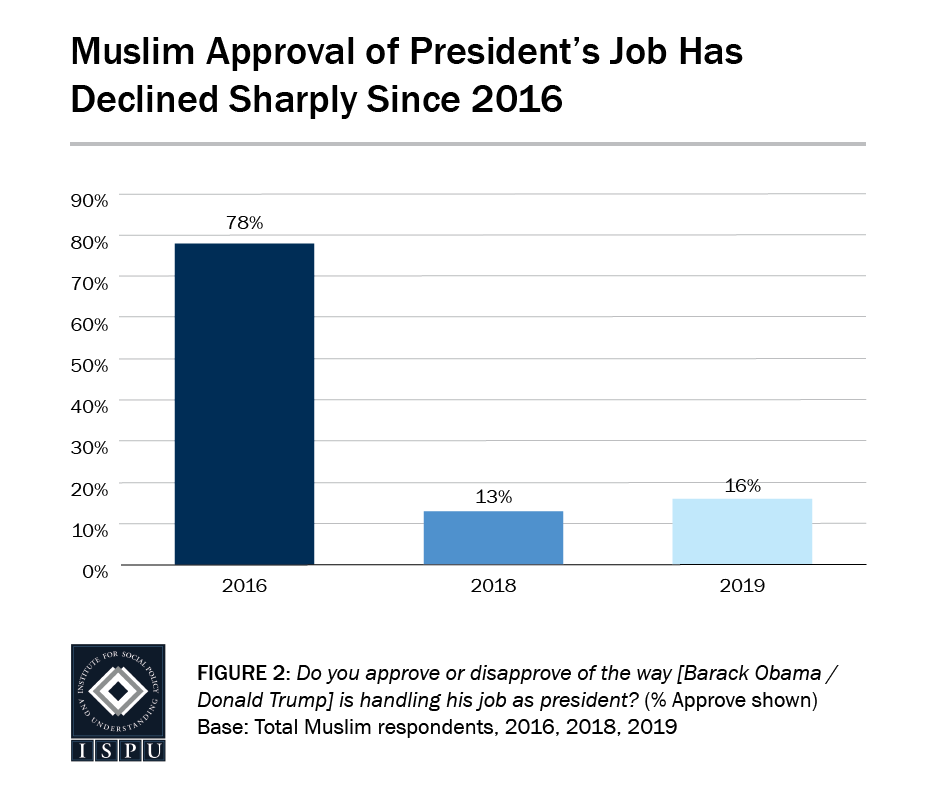

Last year, we reported a tumble in Muslims’ rating of the U.S. President’s job performance (from 78% approval of President Barack Obama’s job performance in 2016 to 13% approval of President Donald Trump’s performance in 2018). Approval ratings in 2019 remain low (Figure 2).

Muslim Dissatisfaction with President Trump Varies by Race and Age

Within the Muslim community, approval of President Trump varies along age and racial lines: White Muslims (29%) and Muslims who are 30-49 years old (19%) are more likely to view Donald Trump positively compared to Muslims who are Arab (12%), Asian (16%), and Black (7%), and Muslims aged 50 and older (8%). Muslims’ approval for Donald Trump decreases as age increases, which is contrary to the trend that prevails among the general population. Nineteen percent of Muslims in the 30-49 year old age bracket report approval of Donald Trump’s job as president, while only 8% of Muslims aged 50 and older feel the same way. Among the general public, Donald Trump is approved of by 37% of those aged 30-49 and approval grows to 46% in the 50 and older group.

Despite Dissatisfaction with the President, Some Muslims Express Optimism with the Direction of the Country

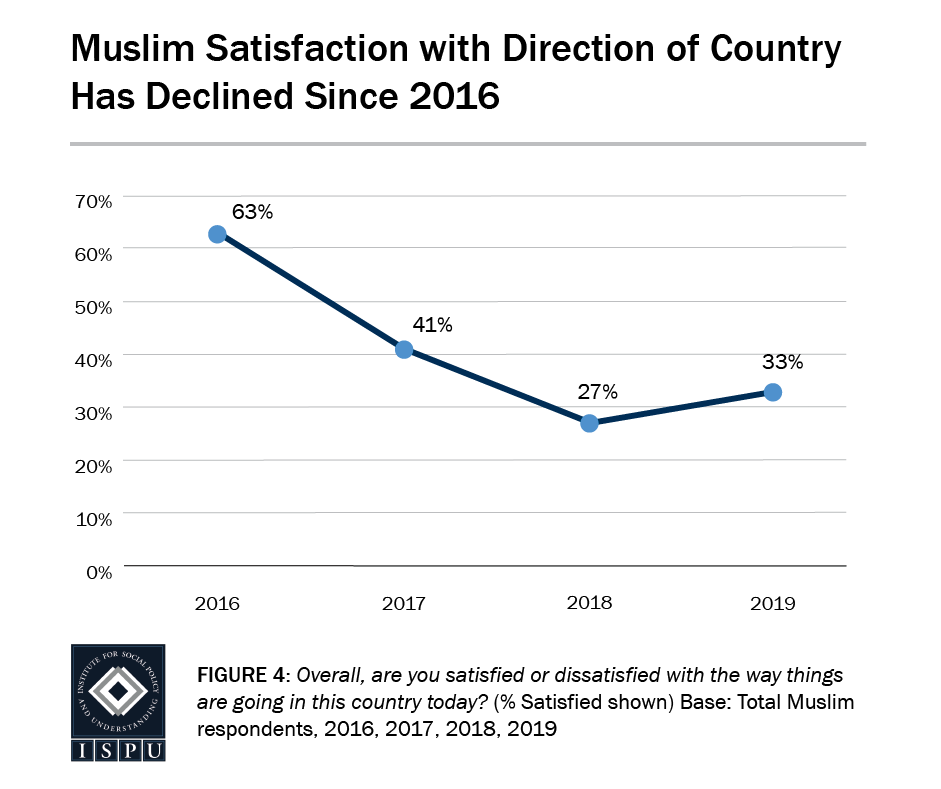

Surprisingly, despite the large portion expressing negative perception of the current administration, a degree of optimism persists in the American Muslim community: 33% of Muslims report being satisfied with the current direction of the nation, more than Jews and the general public (both 19%), Protestants (20%), and non-affiliated Americans (13%). Muslims (33%) are statistically similar to Catholics (25%) and white Evangelicals (24%) in expressing hopefulness.

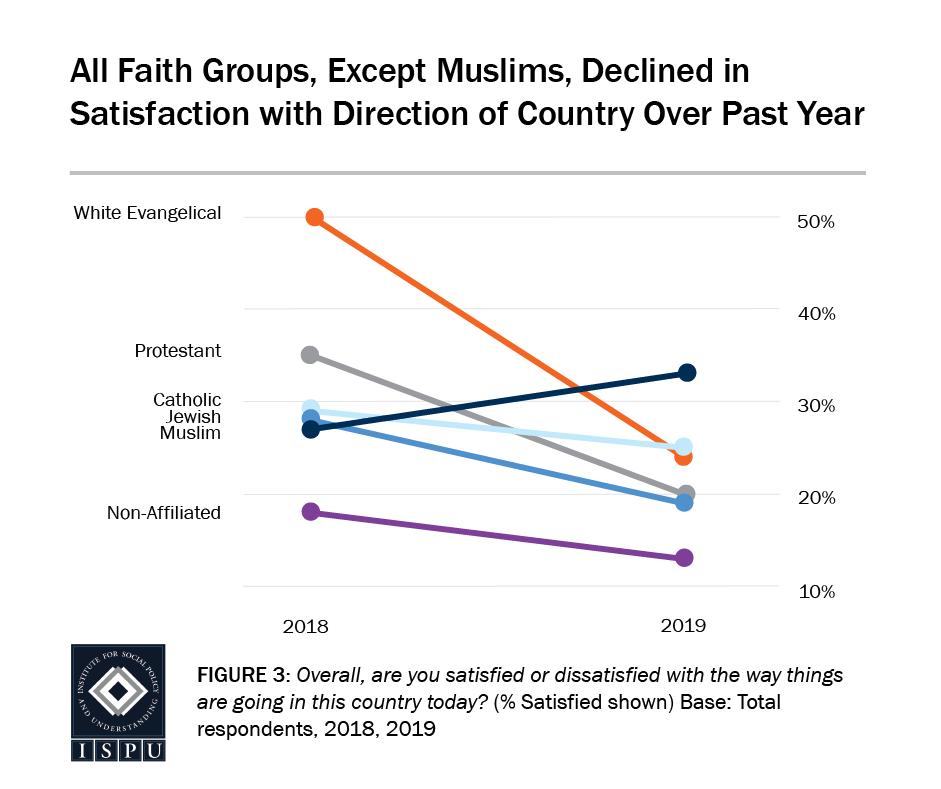

Our data also suggest that all faith groups and non-affiliated Americans show a decline in their satisfaction with the trajectory of the country in 2019 vs. 2018, except Muslims, who have maintained their stance (33% vs. 27%).

This hopefulness is still decisively lower than 2016 (Figure 4), but suggests that in spite of their low opinion of Donald Trump, American Muslims are likely buoyed by two important developments: historic Muslim gains in the 2018 midterm elections and pushback against Trump’s immigration policies. Conversely, satisfaction among white Evangelicals in our sample fell from 50% in 2018 to 24% in 2019.

Fielding this survey (January 8-25, 2019) in the wake of the 2018 midterm elections and during the government shutdown of 2018-2019 has uniquely captured the pulse of Americans. The longest federal government shutdown in U.S. history, which spanned from December 22, 2018, to January 25, 2019, showcased the stiff resistance to Donald Trump’s immigration policies and border wall proposal. The events that reaffirm Muslims’ faith in the future of the nation are likely the reason white Evangelicals, President Donald Trump’s staunchest supporters, in our sample have reported the most significant decrease in satisfaction “with the way things are going in this country” of all groups surveyed. While white Evangelicals’ optimism reduced by nearly half from 50% approval in 2018 to 24% in 2019, Protestants reported a 15 point decrease over 2018 (35% vs. 20%) and the general public reported a 10 point reduction (29% vs. 19%).

To be clear, positive sentiment about the country’s direction within the Muslim community is not uniform. White (43%) and Asian (41%) Muslims are twice as likely to be satisfied than Black Muslims (20%). However, Black Americans who are Muslim report satisfaction at much higher levels than their non-Muslim counterparts in our sample (3%), as do white Muslims compared with white Americans in the general public (43% vs. 20%). It is worth noting that roughly a third (36%) of Black Muslims compared to just 2% of Black Americans overall were born outside of the U.S. In our research, immigrants are often more optimistic about the direction of the country than native-born Americans. Muslim women (70%) are more likely to be dissatisfied about the country’s trajectory than men (58%), though Muslim women’s reported satisfaction is up from 17% in 2018 to 28% in 2019, possibly reflective of encouraging recent events.

Though Growing, Muslim Voter Registration Still Lags Behind Other Groups

Muslims Least Likely to Be Eligible and Registered to Vote

Though the vast majority of Muslims (80%) are eligible to vote, they are the least likely to be so among all faith groups and non-affiliated Americans in our survey. Since roughly half (47%) of American Muslims are born outside of the United States, a significant subset of the group may not have naturalized yet. In comparison, 92% of Jews, 94% of Catholics, 97% of Protestants, 99% of white Evangelicals, 97% of non-affiliated Americans, and 96% of the general population are eligible to vote. Voter eligibility among Muslims has remained relatively stable since 2016.

Among those eligible to vote, Muslims (73%) are still less likely than all other groups to be registered to vote. Other groups tally from 85% (non-affiliated Americans) to 95% (Jews). The gap is most pronounced in the 18-29 age group where Muslim voter registration (63%) is a full 22 points behind the same age group among the general population (85%). Older Muslims’ (88%) registration patterns are similar to the general population (93%). Muslims of all races are equally likely to be registered to vote, as are Muslim men and women.

Overall, voter registration among Muslims has maintained an upward trajectory since 2016 (60%) and 2017 (68%) (Figure 6). However, despite concerted get-out-the-vote efforts ahead of November 2018 midterm elections, the number of registered Muslim voters has remained statistically similar in 2019 (73%) to what it was in 2018 (75%). Roughly a quarter of American Muslims remain disengaged at the ballot box.

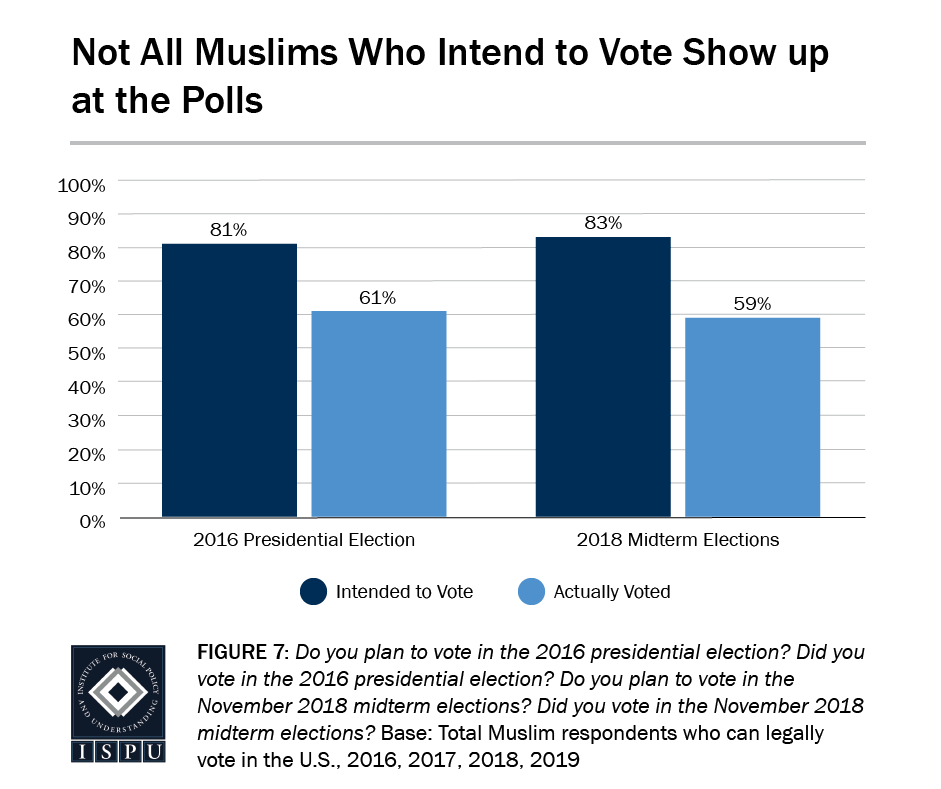

Muslim Voters’ Intentions to Vote Inconsistent with Their Actions

In our 2018 survey, 83% of Muslims expressed their intention to vote in the 2018 midterm elections, while our survey in 2019 found that only 59% actually did. In comparison, 82% among the general public in our sample reported casting their ballots in the 2018 midterms. Similarly in 2016, 81% of Muslims intended to vote in the 2016 presidential elections, while only 61% did (Figure 7). Although some of the discrepancy may be attributed to the social desirability of the appearance of being a voter, for American Muslims, lack of engagement in the electoral process also signals disenchantment with available candidates and the electoral system. In 2017, 42% of Muslims expressed their dissatisfaction with the candidates or lack of trust in the system, which can explain resistance to mobilization efforts and the persistent gaps between word and action when it comes to the ballot.

The story of Muslim participation in American politics is multifaceted. While some Muslims withdraw from it, others seek to change the political landscape of their country. The 2018 midterm elections witnessed historic numbers of Muslim candidates running for public office. That year, 23 Muslims declared candidacy for statewide or national office. Of the seven who won primaries, four won in the general elections. Two of the three elected Muslim members of Congress are women, a first for the U.S. House of Representatives. Keith Ellison, who was the first Muslim to serve in Congress, became the Minnesota Attorney General, the first Muslim to occupy a state-level elected position.

According to an estimate by Emgage, an American Muslim civil rights group, about 100 Muslim candidates filed paperwork to run for various public offices in the 2018 midterm elections, the highest number since the year 2001. Over the years 2016-2018, 276 American Muslims are reported to have run for public office, of whom 131 won. Thirty-six percent of these candidates were women and 64% were men. The highest number of races contested (141) were at the local level, though Muslims also competed for county, state-level, and Congressional positions, as well as judiciary offices at several levels.

Muslim Young Adults’ Voting Trails Behind Peers in General Public

Political engagement varies across age brackets among all groups surveyed, with greater participation by older voters; Muslims are no different. However, Muslim young adults’ participation in the midterms is sluggish in contrast with their generational peers in the general population (52% vs. 72%) as well as compared to their elders in the community (71%). In a record-breaking year when midterm voter turnout was highest since 1914, this apathy may concern those working to increase Muslim political engagement. Our findings, therefore, highlight the need to promote civic engagement among young Muslims. In the future, the importance assigned to a Muslim voting bloc will rely heavily on the voting habits of this cadre of Muslim voters. Community activists and change makers have room to increase the education of young adult Muslims to encourage and sustain meaningful political engagement in the long run.

Though formal political activity appears to have plateaued among young Muslims, they continue to be active in their local communities and engaged in domestic issues. ISPU’s American Muslim Poll in 2017 reported that young adult Muslims show greater support for social justice initiatives such as Black Lives Matter than the general public (71% vs. 53%). Forty-four percent of Muslim youth recounted volunteering to help neighbors solve a community problem, which is on par with youth among Jews, Catholics, Protestants, white Evangelicals, and the general public demonstrating that they are just as invested in their local communities as their generational peers.

Muslims and Jews Most Likely to Have Voted for a Democrat in 2018 Midterms

Our data suggest that Muslims channeled their disapproval of the administration through their vote in the 2018 midterm elections. More than three out of four Muslims (76%) who cast ballots in the 2018 midterms voted for a Democrat, while only 13% voted for a Republican. Across faith groups and those unaffiliated, Muslims are more likely to vote Democratic than any other group surveyed except Jews (69%), who vote similarly (Figure 8). Muslims are about four times more likely to vote Democratic than white Evangelicals (76% vs. 17%). Favoring Democratic candidates is consistent with the trend of three-fourths of Muslims’ self-identification as Democrats or Democratic-leaning in their political beliefs. It is no surprise, then, that over 90% of American Muslim candidates in the 2018 midterm elections are reported to have contested on the Democratic platform.

Older Muslims Lean More Democratic Than Generational Peers in General Public

While Muslims of all ages are likely to vote for Democratic candidates, those aged 50 and older are nearly twice as likely to vote for Democrats than the same age group among the general public (83% vs. 44%). As with the general public, party alignment varies by race in the Muslim community. White Muslims (25%) are more likely than Asian Muslims (9%) to vote Republican and about six times as likely to vote Republican as Black Muslims (4%). Uniquely, Muslims’ voting pattern diverges from the general public—as they age, the general population leans more Republican whereas Muslim Americans continue to identify as strongly Democratic. Among the general public, support for Democrats falls from 70% among young adults (18-29) to 56% among middle-aged Americans (30-49) and further to 44% in the oldest age group (50+). Among Muslims, 75% of young adults and those of middle age vote Democratic, and 83% of those who are 50 and older report the same.

Muslim Local Engagement with Elected Officials a Predictor of Voter Participation More Broadly

What factors predict American Muslims’ voting in the midterms? Fielding this survey soon after the 2018 midterm elections has given insights into patterns of Muslim participation. Unsurprisingly, belonging to a high income bracket and older age group is linked to a greater likelihood of voting in midterm elections, which mirrors trends in the general public.

Remarkably, the level of education attained does not impact voter participation for Muslims, though a college degree is the strongest determinant of participation for the general public.

Mosque attendance stands out as a predictor of civic engagement, as in past surveys. For Muslims, association with their local faith community translates into direct participation in midterm elections. The same holds true for the general public, where weekly attendance of a religious service is also linked to voting in midterm elections.

Mosque attendance stands out as a predictor of civic engagement. For Muslims, association with their local faith community translates into direct participation in midterm elections.

Contacting a local elected official, but not a federal official, emerged as the strongest determinant of midterm participation among Muslims. On average, Muslims who contact local officials are 25% more likely to vote in midterm elections. While it is not surprising that those who make the effort to contact their elected official are also more likely to vote in the midterms, it is noteworthy that this only becomes significant for local officials and not federal officials. This suggests that when Muslims are engaged locally, not just at the federal level, they are more likely to participate overall, even in state and federal elections.

Muslims Less Likely to Communicate with Elected Officials

Our data indicate that Muslims are less likely than all other groups surveyed to communicate with federal and local elected officials. Muslims are half as likely as Jews and Protestants to contact federal elected officials (17% vs. 39%), and similarly lag behind Catholics (27%), white Evangelicals (33%), the non-affiliated (32%), and the general public (31%). While Muslims are about as likely to engage a local official as a federal official, they are less likely than all other faith groups and non-affiliated Americans to contact local elected officials as well. Only 20% of Muslims report communicating with a city or state official in contrast with more than one-third of Jews (38%), Protestants (39%), and white Evangelicals (35%). Among Catholics and non-affiliated Americans, 29% and 30%, respectively, engaged with local officials.

Muslim women (20%) are just as likely as Muslim men (21%) to contact their local officials, as are most women and men of various faith groups in our survey. However, in some instances, men and women’s engagement patterns differ from each other. This is the case among white Evangelicals and Jews. For white Evangelicals, men are far more likely to be involved than women at the local (52% vs. 23%) as well as federal level (48% vs. 22%). On the other hand, among Jews, women (47%) lead men (31%) in federal engagement. Muslim women being as civically engaged as Muslim men is not shocking; our 2017 American Muslim survey found that Muslim women’s donation spending, support for social justice initiatives, and reporting of discrimination outpaces Muslim men.

Muslims aged 50 and older (23%) are more likely than Muslims aged 18-29 (16%) and those aged 30-49 (14%) to contact a federal elected official. This trend is similar to the general public where a greater percentage of older age groups are more likely to contact federal officials. These data reflect the greater overall voter engagement among older Muslims as compared to younger coreligionists. However, middle-aged Muslims’ engagement is significantly lower than that of their generational peers in the general public (14% vs. 28%). Even the most engaged Muslims in the 50+ group fall behind their peers (23% vs. 37%) when it comes to contacting a federal official. Among Muslims, white Muslims (25%) are most likely to get in touch with a federal official. Engagement with a local elected official is similar across age groups among Muslims, ranging from 19% to 22%. Once again, Muslims who are middle-aged or 50 and older lag behind their age groups in the general public (19% vs. 32% and 22% vs. 38%).

Given the strong influence of involvement in local politics on midterm participation and the low levels of Muslims’ involvement in the same, there is an opportunity for Muslims to build local relationships. Investment in their local faith community and the broader public, as well as involvement in local politics can increase Muslims’ buy-in and engagement at the national level.

Support for Muslim Ban Does Little to Help Candidates With Most Voters

In effect since 2017 in various renditions, President Donald Trump’s controversial executive order to impose travel restrictions and ban citizens from five predominantly Muslim countries has been widely debated. Immigration remains in the spotlight in the political arena and candidates support or oppose the so-called “Muslim ban” to indicate their political leaning. How significant, if at all, is a candidate’s endorsement of the Muslim ban to voters?

- Our data reveal that a majority of Muslims, Jews, and non-affiliated Americans say a candidate’s support for the Muslim ban would be reason to decrease their support for this individual’s run for elected office: 61% of Muslims, 53% of Jews, and 56% of non-affiliated Americans hold this view.

- While white Evangelicals (44%) are the most likely of any group to say a candidate’s endorsement of the Muslim ban would increase their support of that candidate. However, a majority of even this faith group, Trump’s strongest supporters, say a candidate’s support for such a policy would either decrease their support (19%) or would make no difference (37%).

- The general public is twice as likely to say a candidate’s endorsement of a Muslim Ban would decrease their support (44%) as increase it (21%), with 34% saying it would make no difference.

These findings suggest that immigration and tourism from the countries included in the Muslim ban are not a major concern for a majority of Americans. Endorsement for this controversial Trump policy is more likely to hurt than help candidates with most voters.

.

Faith and Community

Muslims Profess More Private Religious Devotion, Less Public Religious Assertiveness

Muslims More Likely to Hold Religion Very Important Than All Other Groups, Except White Evangelicals

Muslims (71%) are far more likely to say religion is “very important to their daily lives” than Jews and Catholics (both 35%), Protestants (61%), or the general public (36%). The importance of faith to Muslims is only surpassed by white Evangelicals (82%) in our survey. Noticeably, though white Evangelicals and Muslims diverge in their views in most of our findings, the two groups stand out as the most devoted to their faith amidst a sea of growing secularism.

Though white Evangelicals and Muslims diverge in their views in most of our findings, the two groups stand out as the most devoted to their faith amidst a sea of growing secularism.

Muslim women and men are equally likely to say religion is important to them, despite the greater social cost that Muslim women incur for their faith identity in the form of a greater frequency of reported religious discrimination (55% of men vs. 68% of women). Though Muslim women continue to experience greater religious discrimination than all other groups studied—findings that remain the same in 2019 as in previous years—it has not distanced them from their faith.

The percentage of Muslims who hold religion very important to their daily lives has held steady since 2016.

Muslims as Likely to Attend Religious Services as Protestants

As with previous studies (ISPU poll 2016-2018, Gallup 2009, Pew 2011 and 2016), Muslims are on par with Protestants in religious attendance—43% of Muslims and 49% of Protestants report attending a religious service once a week or more. In our survey, Muslims’ and Protestants’ religious attendance is greater than Jews’ (23%) and Catholics’ (27%), but less than that of white Evangelicals (64%).

Uniquely among Muslims, religious service attendance does not differ by age. In the general public, those aged 50 and over are more likely to attend religious services once a week or more frequently than those in younger age brackets. As such, Muslim 18-29 year olds (31%) are more likely to attend weekly religious services than their peers in the general public (18%). Muslim women are less likely than men to attend a weekly service (29% vs. 55%), explained partially by the fact that traditional Islamic teachings require men to attend Friday congregational prayer and make it optional for women.

It is worth noting, however, that Muslim men and women are equally likely to say they are “satisfied with the way things are done at their house of worship” (78% of men and 79% of women). Overall, Muslims (78%) report being more satisfied with the way their houses of worship are run as compared to Catholics (63%) and the general public (62%).

Muslims aged 50 and older are more likely to be satisfied (89%) with their house of worship than young adults (18-29) and middle-aged (30-49) Muslims (both 76%). It is noteworthy that young adults (52%) and middle-aged Americans (60%) in the general public are also less likely to express satisfaction with their places of worship than their elders ages 50+ (68%). Opinions among Muslims are similar across race.

Muslims Profess More Private Religious Devotion, Less Public Religious Assertiveness

We aimed to measure not only outward religious practice, but the degree to which faith animated one’s inner reality. We designed a section of our survey to gauge private and public spiritual engagement. Two survey questions intended to measure private religious engagement and three captured public religiosity.

Religion in Private Life

We asked survey participants to indicate how much they agreed or disagreed with the following statement:

“Because of my religious faith, I have meaning and purpose in my life.”

This question is a measure of the meaning one draws from their religion. We expected this dimension of personal spirituality to closely track with the importance of religion reported by groups overall, and it does. Once again, Muslims (63%) are more likely than Jews (33%), Catholics (37%), Protestants (54%), and the non-affiliated (6%) to strongly agree with the statement. However, white Evangelicals are the group most likely to strongly agree (75%). Among Muslims, all ages and races are equally likely to find meaning and purpose through religion. In contrast, in the general public, those aged 50 and older as well as Black Americans are more likely to report the same.

Respondents also reported how strongly they agreed or disagreed with the following statement:

“Because of my religious faith, I have forgiven people who have hurt me deeply.”

This question is a measure of the power of faith to overcome vengeance and ego. We found that Muslims (54%) and white Evangelicals (63%) are most likely to “strongly agree” that they have forgiven someone who has hurt them deeply because of their faith, countering the popular trope that Islam teaches vengeance and Christianity forgiveness.

Religion in Public Life

Respondents were asked to choose one of the following statements that is closest to their point of view:

- Your religion should be the MAIN source of American law.

- Your religion should be a source of American law but not the only source.

- Your religion should NOT be a source of American law.

Muslims (33%) are less likely than white Evangelicals (54%) to say they want their religion to be a source of American law but not the only source. Muslims are on par with Catholics (28%), Protestants (39%), and the general public (29%) to hold this view. All these groups are more likely than Jews (19%) and non-affiliated Americans (10%) to agree (Figure 11).

This finding confirms our hypothesis that a group’s wish to link religion to law would mirror the importance of religion to them. These data suggest that people who see their faith as an important part of their personal life also want to see their values reflected in the laws of the land. Muslims are not unique in this regard, nor are they the group most prone to this view.

Within the Muslim community, Arabs (70%) are most likely to see no role for their faith in American law, while other age and racial groups do not differ in their responses. Among the general public, Black Americans (25%) are the most likely to see a role for their faith as the main source of American law.

We asked participants to share how much they agreed or disagreed with the following statement:

“I will take unpopular stands to defend my religious faith.”

This question illustrates one’s readiness, or courage, to take a risk to defend their faith by being “unpopular.” We would expect those who see their faith as important to them to be more likely to express this readiness than others who have a more secular outlook. Some groups surprised us. We found that Muslims (56%) are less likely than Jews (72%) to agree that they will “take unpopular stands to defend their religious faith” despite faith being more important to Muslims than it is to Jews according to the data that measure private devotion. In this instance, Muslims are closer to Catholics (54%) on the spectrum, though they surpass Catholics in the importance of religion in their lives (71% vs. 35% very important) and frequency of religious services (43% vs. 27% once a week or more).

Unsurprisingly, given the importance of religion to their group, roughly three-quarters of white Evangelicals (78%) agree with taking unpopular stands in defense of their faith. This is on par with Jews (72%) despite the sharp difference in their reported private religious devotion.

One reason that can be ascribed to Muslims’ lukewarm support for outspoken displays in defense of their faith is the high incidence of religious discrimination. As a faith group, Muslims report the most frequent religious discrimination (62% vs. 43% or less) and as such have the most to risk with unpopular public displays in defense of their faith.

Finally, we asked survey participants the following question:

“Do you think what happens to members of your faith community in this country will affect you personally?”

This question measures what is termed “linked fate,” [3] how much one feels that their personal lives are impacted by the fate of their religious community. How much solidarity or shared destiny do respondents perceive with their group of co-faithful? The answers would gauge a sense of group cohesiveness, where one’s outcomes are closely linked to those of one’s groups. For instance, those with high levels of “linked fate” would indicate that they are doing well personally if their group is doing well, and they would likewise perceive an attack on the group as being a personal threat.

Our data finds that Muslims (55%) are more likely than Catholics (34%) or the general public (35%) to believe in linked fate, similar to Protestants (55%) and white Evangelicals (57%). Though less pronounced in their religious devotion compared to Muslims and white Evangelicals, Jews (69%) are most likely to express a linked fate with their group. This sense of collective destiny may explain Jews’ willingness to defend their faith in public even if they are not practicing it in their private lives.

Of the three measures of spiritual engagement—(1) meaning and purpose, (2) forgiveness, and (3) unpopular stances to defend it—Muslims are highest on dimensions that reflect private spirituality and lower on the one that requires public risk. White Evangelicals are high on all three, which reflects their public assertiveness and deep personal devotion. Jews are more likely than Muslims to be willing to take unpopular stances, but lag in the dimensions that reflect personal devotion. Catholics are lower on all three, which corresponds to the less pronounced place religion is reported to have in their personal lives.

We have summarized these dimensions in the following framework (Figure 12), placing our surveyed religious communities in one of four quadrants depending on their relative public and private levels of religious engagement.

Protestants and white Evangelicals: At the far upper right-hand side, Protestants and white Evangelicals express strong personal devotion to their faith, consider it an important part of their daily lives, find personal meaning in it, and practice it regularly by attending religious service. They are also more likely to take unpopular stances to defend their faith, see it as a source of legislation, and the majority have a strong sense of “linked fate” with their religious community.

Non-affiliated: At the far lower left-hand corner are non-affiliated Americans, who by definition are low in both membership identity and devotion to a faith, and their responses reflect this.

Catholics: Americans who identify as Catholic are about as likely as Jews, but far less likely than Muslims, Protestants, and especially white Evangelicals to attend a religious service, hold religion important to their daily lives, or derive a strong sense of purpose from their faith. They are also less likely than other Christians to favor taking unpopular stances to defend their faith or to say that their personal fate is intertwined with that of their group. They are more religiously engaged, of course, than non-affiliated Americans, but less so than Muslims and other Christians in their private practice, and less so than Jews and white Evangelicals in their public religious engagement.

Jews: Jews occupy the upper left-hand quadrant: they are lower in their expressed personal or spiritual devotion to their faith, yet more likely than the more religiously devout Muslims and Protestants to be willing to take unpopular stances to defend their faith. Jews are also more likely than Muslims—both religious minorities that face religious discrimination and hate crimes—to see their fate as connected to that of their group. Jews, in fact, share many characteristics of assertive public religious identity with white Evangelicals, but differ in one important dimension of public religious life: their faith as a source of law. Jews are far less likely than white Evangelicals to see a role for their faith in law, and therefore, they are not at the top of the public religious engagement quadrant.

Muslims: Muslims are near the far right-hand end of the private devotion spectrum, but only at the lower middle of the public engagement comparative measure. Muslims are more likely than Catholics, Jews, and non-affiliated Americans to express personal devotion to their faith in their private lives. This applies to the importance of religion to their daily lives, their frequency of attendance of a religious service, and the meaning and purpose they draw from their faith. Muslims are as likely as white Evangelicals to say their faith helped them forgive someone who hurt them deeply, illustrating not just mechanical devotion but the kind that overcomes the ego. And yet, they are as likely as the less personally devoted Catholics, and less likely than the more secular Jews to say they would stand up to defend their faith if the issue were unpopular. Muslims are also less likely than Jews to see their personal fate as connected to their group. However, Muslims surpass Jews on one measure when it comes to public manifestations of faith—their views about seeing their religious values reflected in policy—though Muslims are less likely to hold this view than Protestants and white Evangelicals. Muslims are also the most likely faith community to say they have experienced religious discrimination, and the least likely group studied to enjoy the public’s favorable opinions, which may explain their relative reluctance to take unpopular stances to defend their faith despite its importance to them personally.

Muslims Most Likely to Report Religious, Gender, and Sectarian Discrimination

Religious Discrimination: Who Feels It Worse?

Across all faith groups and non-affiliated Americans we surveyed, Muslims are the most likely group to report experiencing any religious discrimination (62%). The incidence of discrimination reported by Muslims has remained the same since ISPU began tracking it in 2016. As in previous years, Muslim women report higher levels of discrimination than Muslim men: only 31% of Muslim women report never experiencing discrimination as compared to 44% of Muslim men. These trends have remained static over time. While there are no reported racial differences, Muslims aged 18-29 report higher levels of religious discrimination (69%) than Muslims aged 30-49 (58%) and 50+ (52%). Jews (43%) and white Evangelicals (36%) follow Muslims as most likely to be targeted with discrimination.

Sectarianism

Among Muslims, 40% report experiencing some frequency of discrimination (5% regularly, 17% occasionally, and 18% rarely) from another member of their larger faith community because of their sect, as compared to 18-24% of other faith groups. Unlike religious discrimination from broader society that targets women disproportionately, Muslim women and men experience similar levels of sectarian discrimination. However, sectarianism within the Muslim community has a racial dimension: Black Muslims (43%) report higher levels of sectarian discrimination than Arab Muslims (26%).

Intra-Religious and Public Gender Discrimination

As a group, 34% of Muslims report experiencing gender-based discrimination from within their faith community, which is higher than Jews (16%), Protestants (19%), and white Evangelicals (13%), and on par with Catholics (27%) and the general public (36%). However, Muslim women are more likely than Muslim men to say they experience either “occasional” (17% vs. 9%) or “rare” (21% vs. 12%) gender discrimination inside their community. As many as 41% of Muslim women experience gender discrimination at the hands of other Muslims at some frequency. Muslim women are still more likely to experience gender discrimination from outside their religious community than from within it (41% vs. 52%). Muslim women are also more likely than women of any other faith community to report gender discrimination from the public at large (52% vs. 36% or less). Since Muslim women are also more likely to experience religious discrimination than Muslim men (68% vs. 55%), they bear a twofold burden.

Views of Feminism

Muslims (41%) are more likely than white Evangelicals (21%) and Protestants (28%) to have favorable views of feminists and are on par with Catholics (37%). Jews (55%) are the faith group most likely to view feminists positively. Among Muslims, women surpass men in their support for feminism (47% vs. 37%), whereas among other faith groups, women and men are on par. The notion that Muslim women have been socialized into expecting and accepting “second-class status” crumbles under the weight of evidence that shows that they decry gender discrimination inside and outside their community. Moreover, the data show that Muslim women are four times more likely to have favorable opinions as unfavorable opinions (47% vs. 11%) of those who work for women’s empowerment.

Muslims (41%) are more likely than white Evangelicals (21%) and Protestants (28%) to have favorable views of feminists and are on par with Catholics (37%). Jews (55%) are the faith group most likely to view feminists positively.

Muslims Who Experience Discrimination from Other Muslims More Likely to Endorse Anti-Muslim Stereotypes

The Islamophobia Index, which we will discuss in more detail in the next section, is a measure of public endorsement of anti-Muslim stereotypes often perpetuated in the media and in divisive political rhetoric. Muslims are not immune to internalizing this rhetoric, as we discussed at length in the 2018 ISPU poll report “Pride and Prejudice.”

One noteworthy finding is that Muslims who have personally experienced discrimination from other Muslims, either for their sect or gender, are more likely to have a higher score on the Islamophobia Index, meaning they are more prone to endorsing anti-Muslim stereotypes. Negative real-life interactions from other Muslims are linked to a generalized endorsement of negative perceptions of the group, even among Muslims themselves. Muslims experiencing gender discrimination from outside their faith community is also linked to higher scores on the Islamophobia Index for reasons that are not immediately apparent. It is interesting to note that experiencing religious discrimination has no predictive power at all, either in increasing or lowering Islamophobia Index scores.

Muslims Who Experience Discrimination from Other Muslims More Likely to Endorse Anti-Muslim Stereotypes

| Reported Discrimination Type | Link to Higher Islamophobia Index Scores Among Muslims |

| Gender Discrimination (External) | Significant |

| Gender Discrimination (Internal) | Significant |

| Sectarian Discrimination | Significant |

| Religious Discrimination | Not Significant |

| TABLE 1: How often, if at all, have you personally experienced discrimination by someone OUTSIDE your faith community because of your gender in the past year? How often, if at all, have you personally experienced discrimination by someone INSIDE your faith community because of your gender in the past year? How often, if at all, have you personally experienced discrimination in the past year from another member of your larger faith community because of your sect or denomination? How often, if at all, have you personally experienced discrimination in the past year because of your religion? Base: Total respondents, 2019 | |

Though Unwanted Sexual Advances from a Faith Leader Equally Prevalent Across Communities, Muslims Most Likely Group to Report to Law Enforcement

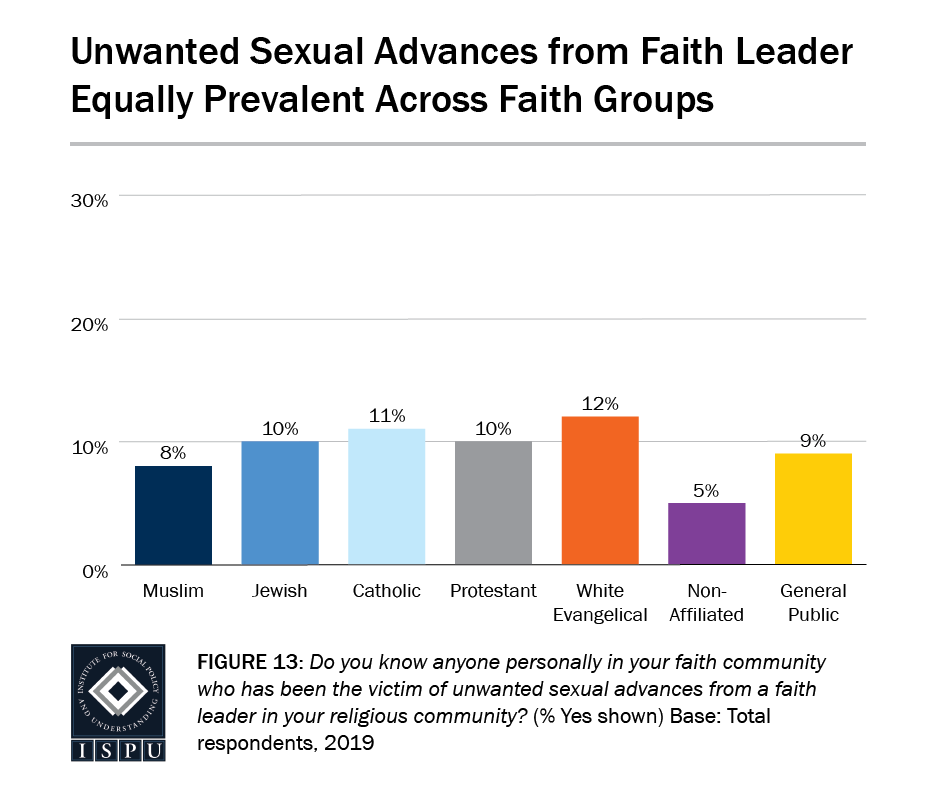

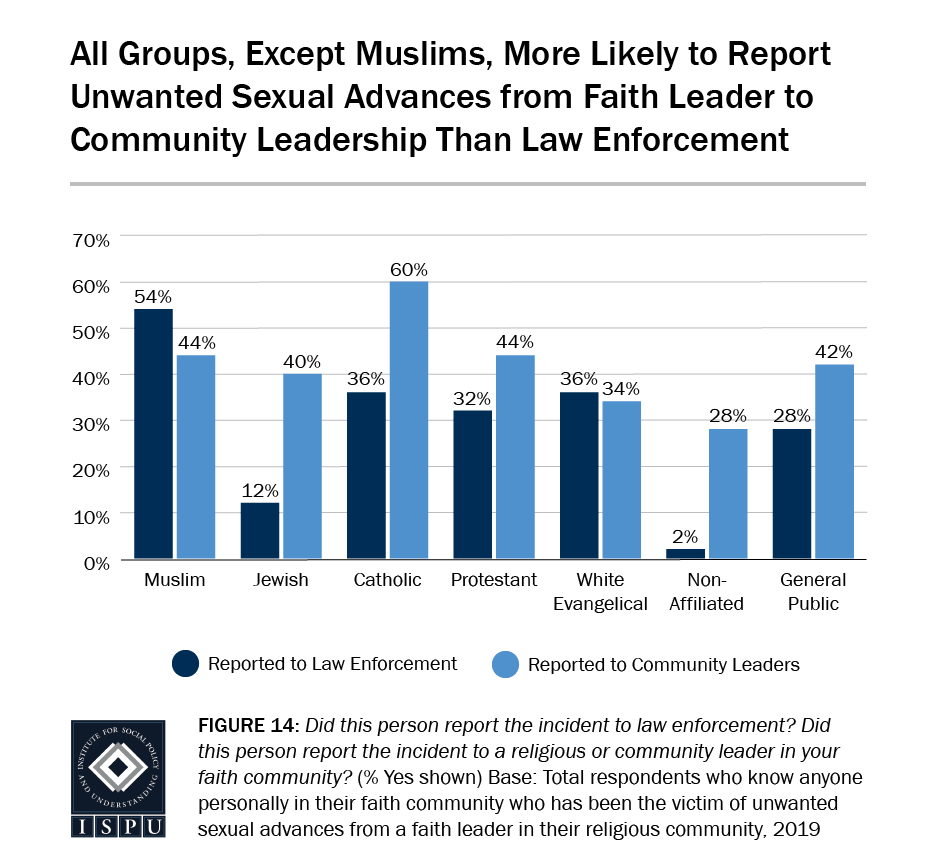

Following a year where sexual violence dominated the news due to the continuing traction of the #MeToo movement and the Brett Kavanaugh hearings for the United States Supreme Court, our survey takes a closer look at how communities approach sexual violence within their ranks. Our data show that roughly 10% of all faith groups say they personally know someone who experienced unwanted sexual advancement from a faith leader in their community (Figure 13).

Though Muslims are no more likely than anyone else to know a person who experienced unwanted sexual advances from a faith leader, they are among the most likely to say this incident was reported to law enforcement (54% vs. 2-36% among other groups).

All faith groups surveyed were equally likely to say the person who experienced unwanted sexual advances from a faith leader in their community reported it to another community or faith leader. However, in every group except Muslims, victims are more likely to have reported the incident internally to their faith leadership than to law enforcement. Though Muslims are as likely as other groups to have also reported the incident to community leadership, unlike other groups, they are slightly more likely (54% vs. 44%) to have reported the incident to law enforcement (Figure 14).

This finding seems to negate the notion of the Muslim community as an exceptionally insular group reluctant to involve law enforcement in their internal affairs. In fact, these data suggest the opposite.

.

The Islamophobia Index

National Islamophobia Index Inches Up

What is the Islamophobia Index? The Islamophobia Index is a measure of the level of public endorsement of five negative stereotypes associated with Muslims in America. These are the items used to construct the index:

Please indicate how much you agree or disagree with the following statements, where 1 means you strongly disagree and 5 means you strongly agree in regards to most Muslims living in the United States.

- Most Muslims living in the United States are more prone to violence than other people.

- Most Muslims living in the United States discriminate against women.

- Most Muslims living in the United States are hostile to the United States.

- Most Muslims living in the United States are less civilized than other people.

- Most Muslims living in the United States are partially responsible for acts of violence carried out by other Muslims.

ISPU analysts chose these five variables based on previous research [4] linking these perceptions with greater tolerance for anti-Muslim policies such as mosque surveillance, racial profiling and greater scrutiny of Muslims at airports, the so-called Muslim ban, and even taking away voting rights from Americans who are Muslims. These five measures are not meant to cover the totality of public Islamophobia, which can and does include many other false beliefs about Muslims. They are instead meant to offer an evidence-based measure of five perceptions known to link to acceptance of discriminatory policies.

It is noteworthy that this index, while called simply “the Islamophobia Index,” only measures anti-Muslim sentiment among the public and not the degree to which Islamophobia is institutionalized by the state. Islamophobia is not simply a phenomenon of societal sentiment, but is a structural phenomenon, manifesting in legislation, budget decisions, and law enforcement practices at the local, state, and federal levels. While our index does not measure structural Islamophobia, public tolerance for many of these practices is linked to higher scores on the Islamophobia Index. [5]

Islamophobia is not simply a phenomena of societal sentiment, but is a structural phenomena, manifesting in legislation, budget decisions, and law enforcement practices.

How did we construct the Islamophobia Index? Answers to this battery of questions were used to construct an additive scale that measures overall anti-Muslim sentiment. [6] The resulting Islamophobia Index provides a single metric that is easy to understand, compare, and track over time. The Islamophobia Index measures the endorsement of anti-Muslim stereotypes (violent, misogynist), perceptions of Muslim aggression toward the United States, degree of Muslim dehumanization (less civilized), and perceptions of Muslim collective blame (partially responsible for violence), all of which have been shown to predict public support for discriminatory policies toward Muslims. [7]

Changes over time: There has been a slight increase in the average overall Islamophobia Index from 24 in 2018 to 28 in 2019 (on a scale of 0 to 100) among the general public. While this is a statistically significant difference, it is not a dramatic uptick.

Jews and Hispanic Americans Are Most Favorable Toward Muslims, White Evangelicals Least

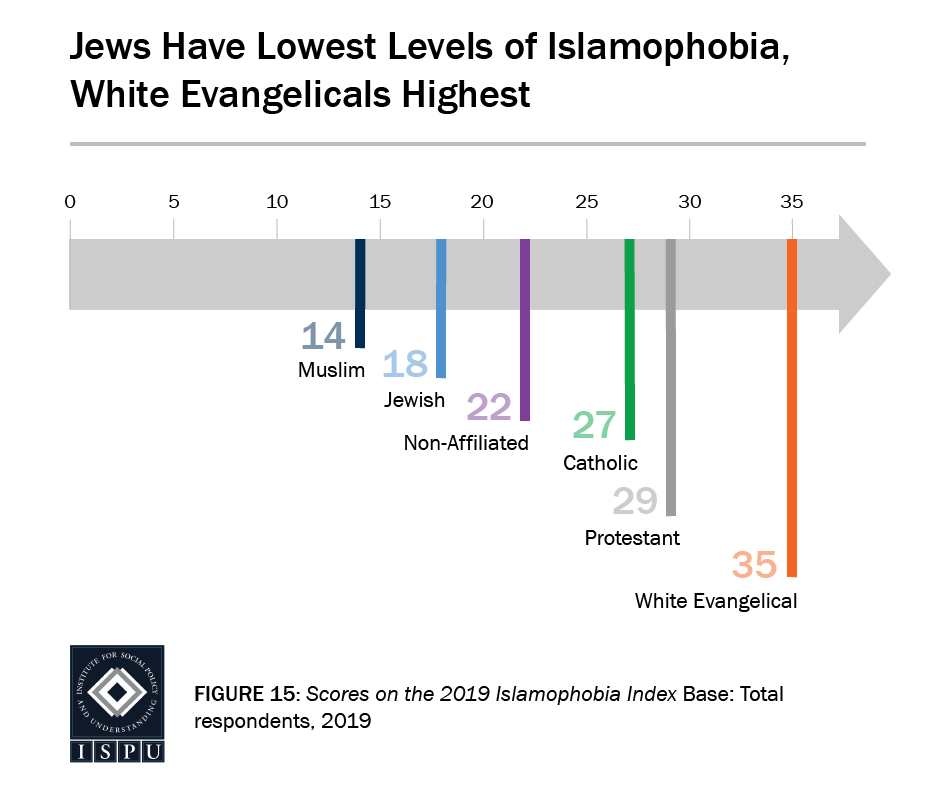

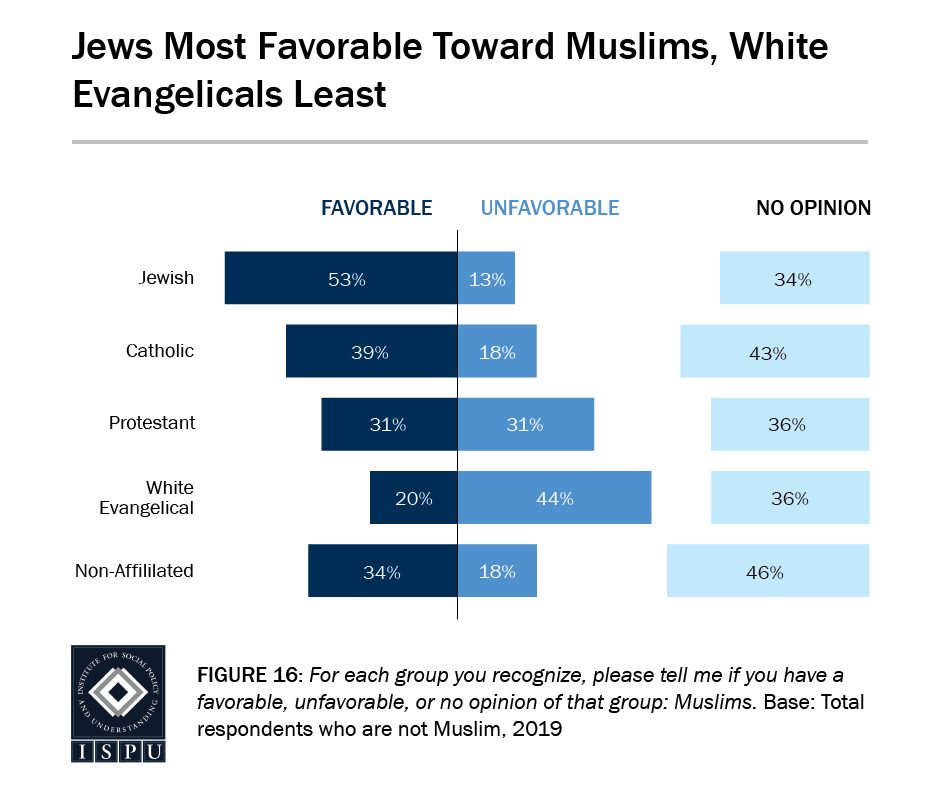

Among faith groups, Jews score the lowest on the Islamophobia Index (18) except for Muslims (14). White Evangelicals score the highest on the Islamophobia Index (35) (Figure 15).

After Muslims themselves, Jews are the most likely to hold positive views of Muslims, with the group five times as likely to hold favorable views (53%) as unfavorable views (13%). This is in sharp contrast to white Evangelicals, where the faith community is more than twice as likely to hold negative views (44%) as positive views (20%) of Muslims (Figure 16).

Among the three main racial groups examined, Hispanic Americans score the lowest on the Islamophobia Index (Figure 17). Hispanic Americans are five times as likely to hold favorable opinions of Muslims as negative (51% vs. 10%) (Figure 18). This is significantly higher than positive opinions held by white Americans (33%) who are almost as likely to hold favorable as unfavorable opinions (26%). The majority of white Americans (40%) have no opinion. Black Americans who are not Muslim are seven times as likely to hold positive opinions (35%) as negative views (5%) of Muslims, but the majority have no opinion (51%)—that opens a door for more positive engagement with this community.

Protective factors: In our 2018 poll report we examined how higher scores on the Islamophobia Index were linked to greater acceptance of authoritarian views, violence against civilians, and anti-Muslim policies. This year, we ask a different question: Rather than what does the index predict, we are now examining what predicts higher and lower scores on the index. In other words, what are the protective factors against Islamophobia, and what are those factors that predict higher scores on the index?

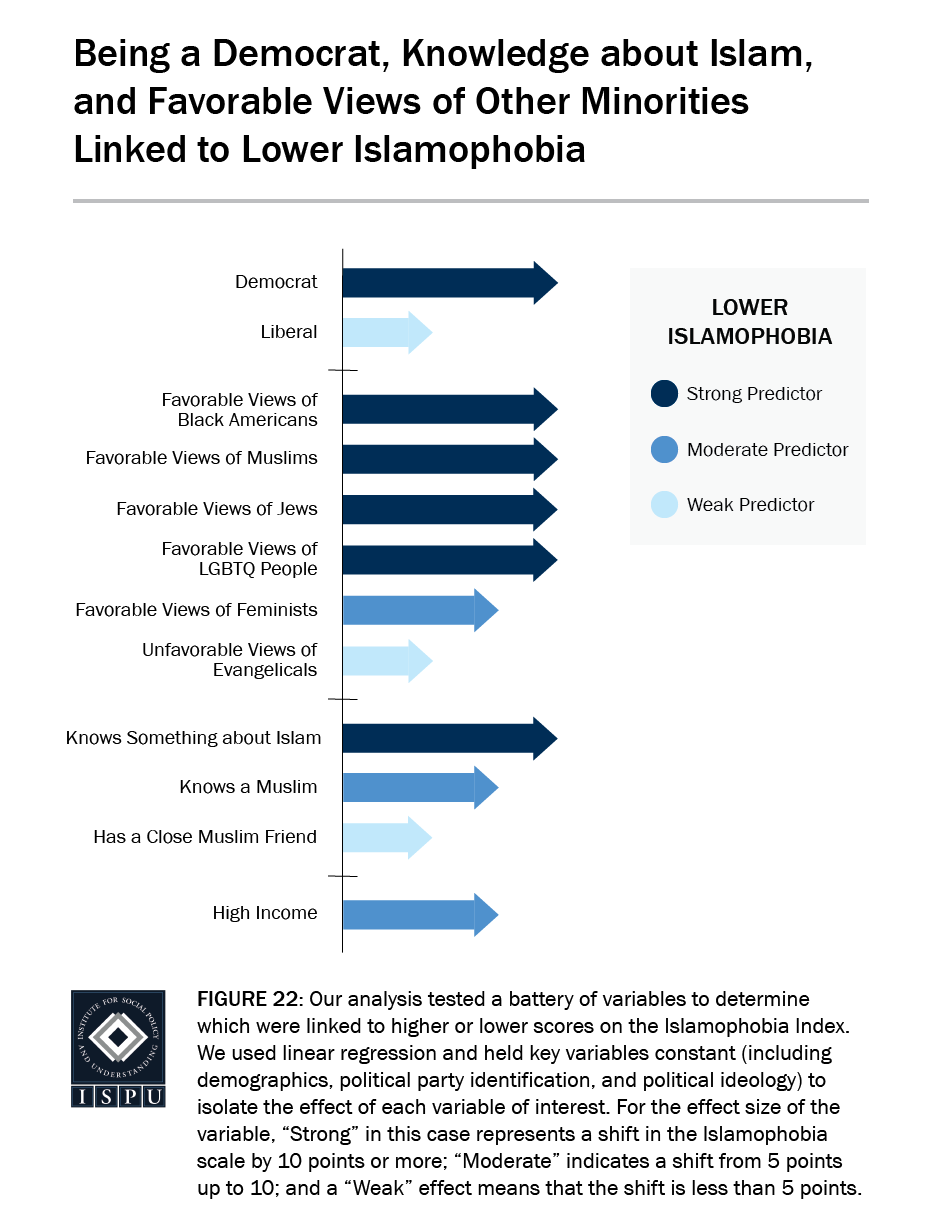

Our analysts tested a battery of variables to determine which were linked to higher or lower scores on the Islamophobia Index. We used linear regression and held key variables constant (including demographics, political party identification, and political ideology) to isolate the effect of each variable of interest (Figure 22). Here is what we discovered:

Knowing a Muslim Linked to Lower Islamophobia

It has long been believed, and previous studies have shown, that greater proximity to a community is associated with more positive views of that community. We wanted to see not only how much “knowing a Muslim” impacted levels of the Islamophobia Index, but how much having a Muslim as a close friend had an impact.

We found that while roughly half of the general public (53%) report knowing an American who is Muslim, only about one-third of white Evangelicals (35%) report the same. In contrast, three-quarters of Jews report knowing a Muslim (Figure 19). Among the general public, the numbers who report knowing a Muslim shows a growing trend—the figure for 2019 (53%) has increased from 45% in 2009 and only 38% in 2001.

Roughly half (47%) of those in the general public who know a Muslim would regard that person as a close friend. Conversely, among white Evangelicals, only a quarter (27%) of an already small base of roughly a third (35%) who know a Muslim at all consider them a close friend. This means that only 9% of white Evangelicals have a close Muslim friend as compared to 45% of Jews.

Jews Most Likely to Know a Muslim

| Jewish | Catholic | Protestant | White Evangelical | Non-Affiliated | General Public | |

| Knows a Muslim personally | 76 | 61 | 44 | 35 | 57 | 54 |

| → Close enough friends with a Muslim that you would call them if you needed help | 45 | 28 | 15 | 9 | 26 | 25 |

| → Not close enough friends with a Muslim that you would call them if you needed help | 31 | 34 | 29 | 25 | 31 | 29 |

| Does not know a Muslim personally | 23 | 39 | 56 | 65 | 43 | 46 |

| TABLE 2: Do you happen to know a Muslim personally, or not? Are there any Muslims you are close enough friends with that you would call them if you needed help? Base: Total respondents, 2019 | ||||||

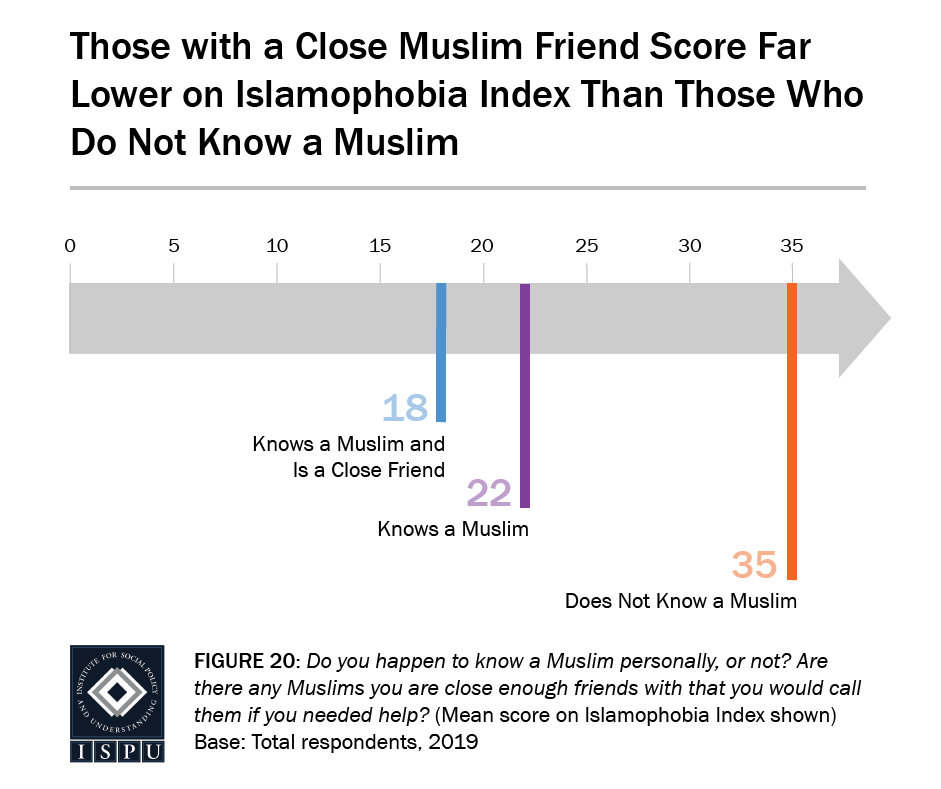

The subset of the general public who know a Muslim score significantly lower on the Islamophobia Index than those who do not know a Muslim (22 vs. 35). Those who know a Muslim well have a mean of 18 on the Islamophobia Index, which is roughly half that of those who do not know a Muslim at all (Figure 20). Remarkably, this score is nearly as low as Muslims themselves score on the same Islamophobia Index, which was 17 in 2018 and is 14 in 2019.

The majority of all three major racial groups know a Muslim, but Hispanic Americans (63%) are more likely to know Muslims than white Americans. Hispanic Americans (39%) are also more likely to have a close Muslim friend than white Americans (21%). It is important to note that Muslims and Hispanic Americans are both groups that are a target of the current administration’s divisive anti-immigrant rhetoric. Resistance movements that demand “No Ban, No Wall” may have helped bring these two groups together.

Hispanic Americans Most Likely to Know a Muslim

| Black | White | Hispanic | |

| Knows a Muslim personally | 51 | 51 | 64 |

| → Close enough friends with a Muslim that you would call them if you needed help |

27 | 21 | 39 |

| → Not close enough friends with a Muslim that you would call them if you needed help |

24 | 30 | 24 |

| Does not know a Muslim personally | 49 | 49 | 36 |

| TABLE 3: Do you happen to know a Muslim personally, or not? Are there any Muslims you are close enough friends with that you would call them if you needed help? Base: Total respondents, 2019 | |||

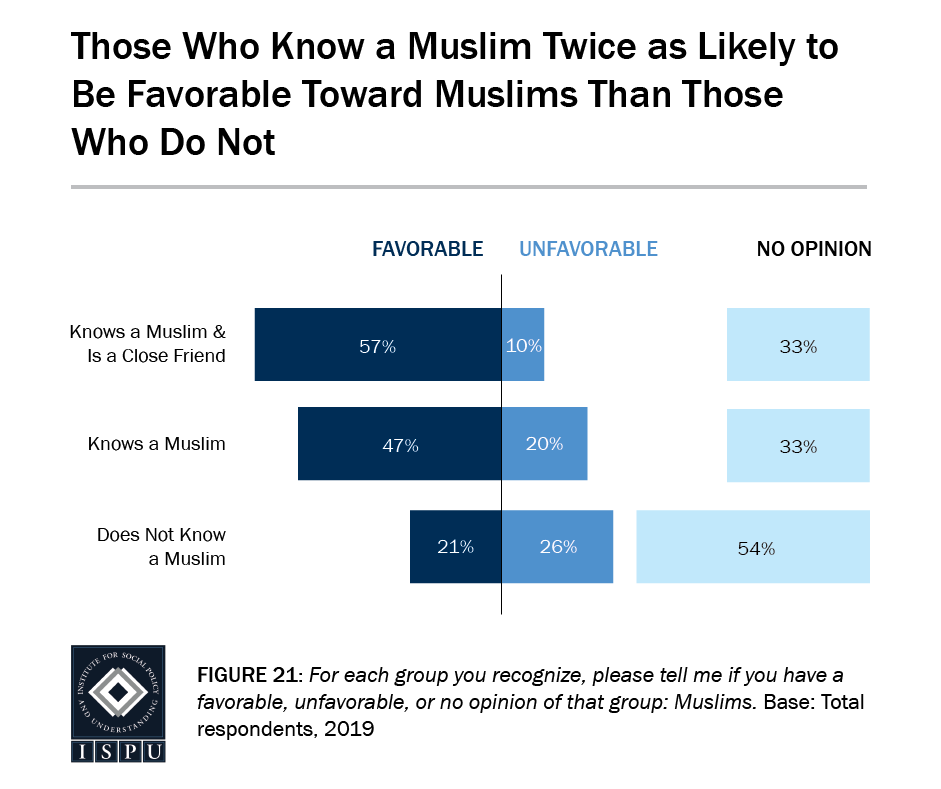

Studying general views of Muslims as people, both favorable or unfavorable, we find that while only 21% of the general public that does not know a Muslim at all has favorable views of Muslims, that number is 57% among those who do know a Muslim and consider that person a close friend (Figure 21). It is striking to note that the biggest improvement in someone’s opinion of all Muslims results from simply knowing a Muslim, and more than doubles from 21% favorable to 47%. Having a Muslim as a good friend increases this number further to 57%, but most of the progress is seen in just becoming familiar with a person who is a Muslim, even if they are not a close friend.

The majority of those who do not know a Muslim say they “have no opinion” about Muslims (54%), while one-quarter hold negative opinions. It appears that knowing a Muslim mostly turns a neutral opinion to a favorable one, but does less to change the percentage of negative opinion (26% vs. 20%). Those who have a good Muslim friend not only report more favorable opinions of the group (57%) than the opinions of those who do not know a Muslim (21%), but having Muslim friends also means they are less likely to have negative opinions of Muslims as a group (10%) compared to those who do not know a Muslim at all (26%).

These data indicate that making Muslim friends would go a long way to cutting Islamophobic perceptions in the public and thus, public acceptance of undemocratic government practices, tolerance for violence, and discrimination toward Muslims, to which higher scores on the Islamophobia Index are linked. [8]

Our findings are also supported by other research; for instance, according to research led by ISPU scholar Muniba Saleem, “Reliance on media for information about Muslims was associated with Americans’ support for public policies targeting Muslims three months later. These policies included military action against Muslim countries, separate and more thorough airport security lines for Muslim travelers, and revoking the right to vote for American Muslims.” Reliance on human contact for information about Muslims, however, produced the opposite effect according to the same research. [9]

Democratic Views, High Income, and Positive Views of Other Minorities Linked to Lower Islamophobia, But Not Higher Education, Youth, or Being Female

Aside from simply knowing a Muslim, we discovered several other perceptions and demographic variables linked to lower Islamophobia, and some were even more powerful predictors of less anti-Muslim bigotry than calling a Muslim a friend.

Predictors of Lower Islamophobia